Fermi's interaction

[1] The theory posits four fermions directly interacting with one another (at one vertex of the associated Feynman diagram).

According to Eugene Wigner, who together with Jordan introduced the Jordan–Wigner transformation, Fermi's paper on beta decay was his main contribution to the history of physics.

[4] Fermi first submitted his "tentative" theory of beta decay to the prestigious science journal Nature, which rejected it "because it contained speculations too remote from reality to be of interest to the reader.

"[5][6] It has been argued that Nature later admitted the rejection to be one of the great editorial blunders in its history, but Fermi's biographer David N. Schwartz has objected that this is both unproven and unlikely.

[7] Fermi then submitted revised versions of the paper to Italian and German publications, which accepted and published them in those languages in 1933 and 1934.

[5] An English translation of the seminal paper was published in the American Journal of Physics in 1968.

This would lead shortly to his famous work with activation of nuclei with slow neutrons.

The operators that change a heavy particle from a proton into a neutron and vice versa are respectively represented by and

, representing the energy of the free light particles, and a part giving the interaction

energy of each such neutrino (assumed to be in a free, plane wave state).

The interaction part must contain a term representing the transformation of a proton into a neutron along with the emission of an electron and a neutrino (now known to be an antineutrino), as well as a term for the inverse process; the Coulomb force between the electron and proton is ignored as irrelevant to the

: first, a non-relativistic version which ignores spin: and subsequently a version assuming that the light particles are four-component Dirac spinors, but that speed of the heavy particles is small relative to

and that the interaction terms analogous to the electromagnetic vector potential can be ignored: where

according to the usual quantum perturbation theory, the above matrix elements must be summed over all unoccupied electron and neutrino states.

According to Fermi's golden rule[further explanation needed], the probability of this transition is where

If the description of the nucleus in terms of the individual quantum states of the protons and neutrons is accurate to a good approximation,

Shortly after Fermi's paper appeared, Werner Heisenberg noted in a letter to Wolfgang Pauli[12] that the emission and absorption of neutrinos and electrons in the nucleus should, at the second order of perturbation theory, lead to an attraction between protons and neutrons, analogously to how the emission and absorption of photons leads to the electromagnetic force.

, but noted that contemporary experimental data led to a value that was too small by a factor of a million.

[13] The following year, Hideki Yukawa picked up on this idea,[14] but in his theory the neutrinos and electrons were replaced by a new hypothetical particle with a rest mass approximately 200 times heavier than the electron.

[15] Fermi's four-fermion theory describes the weak interaction remarkably well.

Unfortunately, the calculated cross-section, or probability of interaction, grows as the square of the energy

Since this cross section grows without bound, the theory is not valid at energies much higher than about 100 GeV.

Here GF is the Fermi constant, which denotes the strength of the interaction.

This eventually led to the replacement of the four-fermion contact interaction by a more complete theory (UV completion)—an exchange of a W or Z boson as explained in the electroweak theory.

[16] In the original theory, Fermi assumed that the form of interaction is a contact coupling of two vector currents.

Subsequently, it was pointed out by Lee and Yang that nothing prevented the appearance of an axial, parity violating current, and this was confirmed by experiments carried out by Chien-Shiung Wu.

[17][18] The inclusion of parity violation in Fermi's interaction was done by George Gamow and Edward Teller in the so-called Gamow–Teller transitions which described Fermi's interaction in terms of parity-violating "allowed" decays and parity-conserving "superallowed" decays in terms of anti-parallel and parallel electron and neutrino spin states respectively.

Before the advent of the electroweak theory and the Standard Model, George Sudarshan and Robert Marshak, and also independently Richard Feynman and Murray Gell-Mann, were able to determine the correct tensor structure (vector minus axial vector, V − A) of the four-fermion interaction.

[19][20] The most precise experimental determination of the Fermi constant comes from measurements of the muon lifetime, which is inversely proportional to the square of GF (when neglecting the muon mass against the mass of the W boson).

In the Standard Model, the Fermi constant is related to the Higgs vacuum expectation value More directly, approximately (tree level for the standard model), This can be further simplified in terms of the Weinberg angle using the relation between the W and Z bosons with

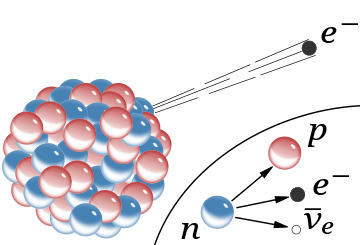

β −

decay in an atomic nucleus (the accompanying antineutrino is omitted). The inset shows beta decay of a free neutron. In both processes, the intermediate emission of a virtual

W −

boson (which then decays to electron and antineutrino) is not shown.