Ferrara

[5] The ruins of the Etruscan town of Spina, established along the lagoons at the ancient mouth of Po river, were lost until modern times, when drainage schemes in the Valli di Comacchio marshes in 1922 first officially revealed a necropolis with over 4,000 tombs, evidence of a population centre that in Antiquity must have played a major role.

[6] There is uncertainty among scholars about the proposed Roman origin of the settlement in its current location (Tacitus and Boccaccio refer to a "Forum Alieni"[7]), for little is known of this period,[8] but some archeologic evidence points to the hypothesis that Ferrara could have been originated from two small Byzantine settlements: a cluster of facilities around the Cathedral of St. George, on the right bank of the main branch of the Po, which then ran much closer to the city than today, and a castrum, a fortified complex built on the left bank of the river to defend against the Lombards.

[14][15] Upon his death in 1534, Alfonso I was succeeded by his son Ercole II, whose marriage in 1528 to the second daughter of Louis XII, Renée of France, brought great prestige to the court of Ferrara.

Ferrara, a university city second only to Bologna, remained a part of the Papal States for almost 300 years, an era marked by a steady decline; in 1792 the population of the town was only 27,000, less than in the 17th century.

A bastion fort was erected in the 1600s by Pope Paul V on the site the Castel Tedaldo, an old castle at the south-west angle of the town, this was occupied by an Austrian garrison from 1832 until 1859.

[17] During the last decades of the 1800s and the early 1900s, Ferrara remained a modest trade centre for its large rural hinterland that relied on commercial crops such as sugar beet and industrial hemp.

After the war, the industrial area in Pontelagoscuro was expanded to become a giant petrochemical compound operated by Montecatini and other companies, that at its peak employed 7,000 workers and produced 20% of plastics in Italy.

[20] In recent decades, as part of a general trend in Italy and Europe, Ferrara has come to rely more on tertiary and tourism, while the heavy industry, still present in the town, has been largely phased out.

[4] The proximity to the largest Italian river has been a constant concern in the history of Ferrara, that has been affected by recurrent, disastrous floods, the latest occurring as recently as 1951.

114), the Municipal Statute[26] and several laws, notably the Legislative Decree 267/2000 or Unified Text on Local Administration (Testo Unico degli Enti Locali).

[27] The current division of the seats in the city council, after the 2019 local election, is the following: The imposing Este Castle, sited in the very centre of the town, is iconic of Ferrara.

A very large manor house featuring four massive bastions and a moat, it was erected in 1385 by architect Bartolino da Novara with the function to protect the town from external threats and to serve as a fortified residence for the Este family.

[29] The duomo has been renovated many times through the centuries, thus its resulting eclectic style is a harmonious combination of the Romanesque central structure and portal, the Gothic upper part of the façade and the Renaissance campanile.

[4] The marble campanile attributed to Leon Battista Alberti[30] was initiated in 1412 but is still incomplete, missing one projected additional storey and a dome, as it can be observed from numerous historical prints and paintings on the subject.

It was the private residence of merchant Giovanni Romei, related by marriage to the Este family, and likely the work of the court architect Pietrobono Brasavola.

The northern quarter, which was added by Ercole I in 1492–1505 thanks to the master plan of Biagio Rossetti, and hence called the Addizione Erculea, features a number of Renaissance palazzi.

The palazzo houses the National Picture Gallery, with a large collection of the school of Ferrara, which first rose to prominence in the latter half of the 15th century, with Cosimo Tura, Francesco Cossa and Ercole dei Roberti.

Noted masters of the 16th-century School of Ferrara include Lorenzo Costa and Dosso Dossi, the most eminent of all,[4] Girolamo da Carpi and Benvenuto Tisi (il Garofalo).

On 15 April, Lieutenant Field Marshal Johann von Klenau approached the fortress with a modest mixed force of Austrian cavalry, artillery and infantry augmented by Italian peasant rebels, commanded by Count Antonio Bardaniand and demanded its capitulation.

The Jewish residents of Ferrara paid 30,000 ducats to prevent the pillage of the city by Klenau's forces; this was used to pay the wages of Gardani's troops.

On December 13, 2017, the first day of Hanukkah, Italy's Museum of Italian Judaism and the Shoah opened on the site of a restored two-story brick prison built in 1912 that counted Jews among its detainees during the Fascist period.

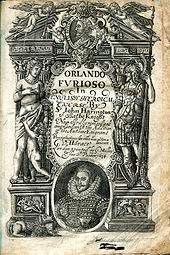

[38][39] During the Renaissance the Este family, well known for its patronage of the arts, welcomed a great number of artists, especially painters, that formed the so-called School of Ferrara.

In the 20th century, Ferrara was the home and workplace of writer Giorgio Bassani, well known for his novels that were often adapted for cinema (The Garden of the Finzi-Continis, Long Night in 1943).

He vehemently preached against the moral corruption of much of the clergy at the time, and his main opponent was Pope Alexander VI (Rodrigo Borgia).

During the time that Renée of France was Duchess of Ferrara, her court attracted Protestant thinkers such as John Calvin and Olympia Fulvia Morata.

[40] The court became hostile to Protestant sympathizers after the marriage of Renée's daughter Anna d'Este to the fervently Catholic Duke of Guise.

The town was also the setting of the famous 1970 movie The Garden of the Finzi-Continis by Vittorio De Sica, that tells the vicissitudes of a rich Jewish family during the dictatorship of Benito Mussolini and World War II.

Furthermore, Wim Wenders and Michelangelo Antonioni's Beyond the Clouds in (1995) and Ermanno Olmi's The Profession of Arms in (2001), a film about the last days of Giovanni dalle Bande Nere, were also shot in Ferrara.

The culinary tradition of Ferrara features many typical dishes that can be traced back to the Middle Ages, and that sometimes reveals the influence of its important Jewish community.

It is often followed by salama da sugo, a very big, cured sausage made from a selection of pork meats and spices kneaded with red wine.