Fiat money

Empirical methods Prescriptive and policy Fiat money is a type of government-issued currency that is not backed by a precious metal, such as gold or silver, nor by any other tangible asset or commodity.

Since President Richard Nixon's decision to suspend US dollar convertibility to gold in 1971, a system of national fiat currencies has been used globally.

[10] In monetary economics, fiat money is an intrinsically valueless object or record that is accepted widely as a means of payment.

In 1787 George Washington wrote to Jabez Bowen, regarding the Rhode Island pound: "Paper money has had the effect in your State that it ever will have, to ruin commerce—oppress the honest, and open a door to every species of fraud and injustice.

In the Grundrisse (1857-58), Karl Marx considered the modern economic ramifications of a historical switch to fiat money from the gold or silver-commodity.

Would the bank not have been equally forced to raise the terms of its discounting precisely at the moment when its "public" clamoured most eagerly for its services?

"Commenting on the passage, Marxist economist and geographer David Harvey writes that "[t]he consequence, as Marx saw it, would be that "the directly exchangeable wealth of the nation" would be ‘absolutely diminished’ alongside of ‘an unlimited increase of bank drafts’ (i.e., accelerating indebtedness) with the direct consequence of ‘increase in the price of products, raw materials and labour’ (inflation) alongside a ‘decrease in price of bank drafts’ (ever-falling rates of interest)."

Harvey notes the accuracy of the modern economy in this way, save for "...the rising prices of labor and means of production (low inflation except for assets such as stocks and shares, land and property and resources such as water rights).

"[13] The latter point can be explained by the private exportation of debt,[14] labour, and figurative and/or literal waste[15] to the global periphery, a concept related to metabolic and carbon rift.

The government made several attempts to maintain the value of the paper money by demanding taxes partly in currency and making other laws, but the damage had been done, and the notes became disfavored.

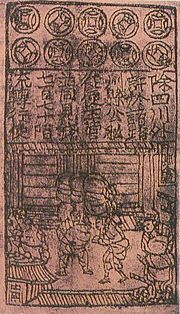

During the 13th century, Marco Polo described the fiat money of the Yuan dynasty in his book The Travels of Marco Polo:[20][21] All these pieces of paper are issued with as much solemnity and authority as if they were of pure gold or silver... and indeed everybody takes them readily, for wheresoever a person may go throughout the Great Kaan's dominions he shall find these pieces of paper current, and shall be able to transact all sales and purchases of goods by means of them just as well as if they were coins of pure gold.According to a travelogue of a visit to Prague in 960 by Ibrahim ibn Yaqub, small pieces of cloth were used as a means of trade, with these cloths having a set exchange rate versus silver.

In 1661, Johan Palmstruch issued the first regular paper money in the West, by royal charter from the Kingdom of Sweden, through a new institution, the Bank of Stockholm.

Jacques de Meulles, the Intendant of Finance, conceived an ingenious ad hoc solution – the temporary issuance of paper money to pay the soldiers, in the form of playing cards.

Because of the chronic shortages of money of all types in the colonies, these cards were accepted readily by merchants and the public and circulated freely at face value.

After the British conquest in 1760, the paper money became almost worthless, but business did not end because gold and silver that had been hoarded came back into circulation.

The Royal Canadian Mint still issues Playing Card Money in commemoration of its history, but now in 92.5% silver form with gold plate on the edge.

Examples are During the American Civil War, the Federal Government issued United States Notes, a form of paper fiat currency known popularly as 'greenbacks'.

[31] Immediately after World War I, governments and banks generally still promised to convert notes and coins into their nominal commodity (redemption by specie, typically gold) on demand.

[32] Other currencies were calibrated with the U.S. dollar at fixed rates: for example the pound sterling traded for many years within a narrow band centred on US$2.80.

In the United States, the Coinage Act of 1965 eliminated silver from circulating dimes and quarter dollars, and most other countries did the same with their coins.

[34] The Canadian penny, which was mostly copper until 1996, was removed from circulation altogether during the autumn of 2012 due to the cost of production relative to face value.

The Bank for International Settlements published a detailed review of payment system developments in the Group of Ten (G10) countries in 1985, in the first of a series that has become known as "red books".

[39] A red book summary of the value of banknotes and coins in circulation is shown in the table below where the local currency is converted to US dollars using the end of the year rates.

[40] The value of this physical currency as a percentage of GDP ranges from a maximum of 19.4% in Japan to a minimum of 1.7% in Sweden with the overall average for all countries in the table being 8.9% (7.9% for the US).

The adoption of fiat currency by many countries, from the 18th century onwards, made much larger variations in the supply of money possible.

[43][41] Economists generally believe that high rates of inflation and hyperinflation are caused by an excessive growth of the money supply.

[45] Small (as opposed to zero or negative) inflation reduces the severity of economic recessions by enabling the labor market to adjust more quickly to a recession, and reduces the risk that a liquidity trap (a reluctance to lend money due to low rates of interest) prevents monetary policy from stabilizing the economy.