Extrasolar planets in fiction

Indeed, one activity associated with hard science fiction is "world building", meticulously crafting bizarre planets that nonetheless accord with all scientific laws.

[5][6] The majority of extrasolar planets in fiction are inhabited by native species,[4] and humans are variously depicted as being integrated into or remaining apart from such alien ecosystems.

[9] In Hal Clement's 1953 novel Mission of Gravity, the planet Mesklin's rapid rotation causes it to be shaped roughly like a flat disk and gravity is consequently about 200 times weaker at the equator than it is at the poles,[1][9][10] while the moon Jinx in Larry Niven's 1975 short story "The Borderland of Sol" is instead stretched by tidal forces from the planet it orbits rather than flattened, resulting in a prolate spheroid shape where the equator is covered by an atmosphere but the poles rise up above it.

[9] Double planets close enough together to share an atmosphere through their Roche lobes appear in Homer Eon Flint's 1921 short story "The Devolutionist", Robert L. Forward's 1982 novel Rocheworld (a.k.a.

[3][9][14][15] A planet in the shape of a torus is the setting of Flint's 1921 short story "The Emancipatrix", being the result of the protoplanetary disk condensing so quickly that it did not coalesce into a spherical shape first; an artificial planet-sized torus also appears in John P. Boyd [Wikidata]'s 1981 short story "Moonbow", while Niven wrote of a much larger toroidal megastructure in space in the 1970 novel Ringworld and a much smaller one in the 1973 novel Protector.

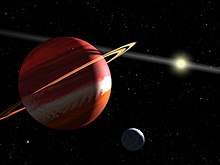

[18] Hal Clement's 1957 novel Cycle of Fire depicts a planet in a binary star system where the seasons last for decades and different species dominate the hot and cold parts of the year,[1][14][19] Poul Anderson's 1974 novel Fire Time portrays a planet where the majority of the surface becomes uninhabitable approximately once a millennium when it makes a close approach to one of its stars and mass migration of the native lifeforms ensues,[18] and Brian Aldiss's 1982–1985 Helliconia trilogy is set on a planet where the orbital mechanics lead to century-long seasons and there are two distinct ecosystems—one adapted to the short period around the closer star and another adapted to the long year around the more distant one.

[1][3][31] Desert planets are common; astrophysicist Elizabeth Stanway [Wikidata] posits that this is because the setting strikes the right balance between novelty and familiarity to most audiences, in addition to the relative inhospitality providing a survival aspect to the narrative.

[33] One of the most prominent examples thereof is Arrakis in Frank Herbert's 1965 novel Dune, where the extreme scarcity of water influences all aspects of the planet's ecology and society.

[34][35][36] One of the planets in the 2014 film Interstellar is covered by a shallow ocean and orbits so closely around a black hole that there are both tidal waves the height of mountains and extreme time dilation.

[1][38] Sentient planets appear in Ray Bradbury's 1951 short story "Here There Be Tygers", Stanisław Lem's 1961 novel Solaris, and Terry Pratchett's 1976 novel The Dark Side of the Sun.

[38] The related concept known as the Gaia hypothesis—an entire planetary ecosphere functioning as a single organism, often but not always imbued with a planet-wide consciousness—is more common; examples include Murray Leinster's 1949 short story "The Lonely Planet", Isaac Asimov's 1982 novel Foundation's Edge, and the 2009 film Avatar.