Field of Mars (Saint Petersburg)

Over its long history it has been alternately a meadow, park, pleasure garden, military parade ground, revolutionary pantheon and public meeting place.

The space now covered by the Field of Mars was initially an open area of swampy land between the developments around the Admiralty, and the imperial residence in the Summer Garden.

It was drained by the digging of canals in the first half of the eighteenth century, and initially served as parkland, hosting a tavern, post office and the royal menagerie.

Popular with the nobility, several leading figures of Petrine society established their town houses around the space in the mid eighteenth century.

During the reigns of Emperor Paul I and his son Alexander I, the square took on more of a martial purpose, with the construction of military monuments in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.

(Renaming took place in 1818, not 1805, according to the Oxford Revised edition of War And Peace) The square was part of the further development of the area by architect Carlo Rossi in the late 1810s, involving new buildings around the perimeter, and the extension of streets and frontages.

The monument became the centre of an early pantheon of those who died in the service of the nascent Soviet state, and burials of some of the dead of the October Revolution and the Russian Civil War, as well as prominent figures in the government, took place between 1917 and 1933.

[2] In the early 18th century the land which eventually became the Field of Mars was a marshy area with trees and shrubs, lying between the Neva to the north, and the Mya (now the Moyka) and Krivusha (now the Griboyedov Canal) rivers to the south.

Those that settled in the area included Charles Frederick, Duke of Holstein-Gottorp, Alexander Rumyantsev, Adam Veyde, and Pavel Yaguzhinsky, and Peter the Great's daughter, Elizabeth Petrovna.

[3] With the canals dug to carry away water, the land was soon drained, and on the orders of Peter the Great, it was levelled, cleared and sown with grass, with alleys laid out for walking and riding.

Architect Mikhail Zemtsov designed 24 garden pavilions, and oversaw the laying out of new paths and tree planting carried out by Harmen van Bol'es and his apprentice Ilya Surmin.

[3] In 1750 a theatre, designed by Rastrelli, was built on the square, replacing an earlier one that had stood on the corner of the Catherine Canal and Nevsky Prospect but had burnt down in 1749.

[2] It also hosted the Maly Theatre on the banks of the Moyka, and was the venue of a German troupe led by Karl Knipper, which performed with the pupils of the city's Foundling Home.

Ivan Dmitrevsky, an actor in the troupe, and later its director, arranged for it to present the first productions of comedic works by Denis Fonvizin, including The Brigadier and The Minor.

[3] The city continued to expand during the second half of the eighteenth century and large townhouses and palaces were built along the northern boundary of the meadow, along the Neva embankment.

[3] Yury Felten designed the three-storey Lombard building to replace the Razumovsky residence on the west side of the meadow, at the junction with the prestigious Millionnaya Street.

[2] The new name also referenced the Campus Martius in Rome and the Champ de Mars in Paris, drawing parallels and asserting that Saint Petersburg was also to be considered as a great European capital.

Pushkin acknowledged the military connection in his 1833 poem The Bronze Horseman; I love the military vigourParaded on the Field of Mars:Stout-hearted foot troops and hussarsIn orderly and pleasing figure;Torn battle colours held on high;Smart ranks in measured rhythm swaying;Glint of brass helmets, all displayingProud bullet scars from wars gone by.

[7] Military use trampled the remaining grassy surface to dust, which when raised by the soldiers' boots, blew across the city, often settling in the trees of the nearby Summer Garden, and earning the Field of Mars its nickname of the "Saint Petersburg Sahara".

[3][4] The next major redevelopment of the area was in 1818, with architect Carlo Rossi including it in the development of his architectural ensemble to the south, centred around the Mikhailovsky Palace estate.

[4] Reviews of the Guard Corps were held every May, prior to the Imperial family's departure for its summer residences, along with parades to mark important events.

[8] Another review was held on the field on 21 April 1856, marking the ceremonial disbanding of regiments of the national militia that had been raised for service in the Crimean War.

The farce is played briskly...[3] The artist Mstislav Dobuzhinsky recalled visiting a fair on the field when a child:Approaching the Field of Mars, where the booths stood, already from the Chain Bridge and even earlier, from Panteleimonovskaya, I heard the shaking of the human rumble and a whole sea of sounds - horns, and the squeak of whistles, and the mournful sound of the street-organ, the accordion, and the banging of tambourines, and individual cries — all this drew me on, and with all my strength I hurried my nanny to get there as quickly as possible.

Other failed proposals included that in 1913 to return the Rumyantsev Obelisk to the Field of Mars, and the creation of a shopping centre with a hotel, a restaurant and a post office.

In 1909, Franz Roubaud's panoramic painting "The Defence of Sevastopol" was displayed on the Field of Mars in a special pavilion designed by Vasily Shene.

[3] After the February Revolution, the Petrograd Soviet decided to create an honorary communal burial ground for those who had been killed in the unrest, and the Field of Mars was selected.

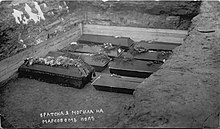

[3] Ultimately only 184 victims were buried on the Field of Mars, comprising 86 soldiers, 9 sailors, 2 officers, 32 workers, 6 women, 23 people for whom social status could not be determined, and 26 unknown dead.

The graves had been prepared by blasting trenches in the frozen ground, with the lowering of each coffin marked by a cannon shot from the Peter and Paul Fortress.

Police detained 658 people, including Maksim Reznik [ru], a deputy of the Legislative Assembly of Saint Petersburg, and several journalists.

[18] In August 2017 Poltavchenko revoked the "Hyde Park" status of the Field of Mars, citing the nature of the burials and memorial made it an inappropriate location for rallies.

by Benjamin Patersen .