Fifteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution

In the final years of the American Civil War and the Reconstruction Era that followed, Congress repeatedly debated the rights of the millions of black freedmen.

[3]In the final years of the American Civil War and the Reconstruction Era that followed, Congress repeatedly debated the rights of black former slaves freed by the 1863 Emancipation Proclamation and the 1865 Thirteenth Amendment, the latter of which had formally abolished slavery.

Following the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment by Congress, however, Republicans grew concerned over the increase it would create in the congressional representation of the Democratic-dominated Southern states.

[5][6][7] In 1865, Congress passed what would become the Civil Rights Act of 1866, guaranteeing citizenship without regard to race, color, or previous condition of slavery or involuntary servitude.

The bill also guaranteed equal benefits and access to the law, a direct assault on the Black Codes passed by many post-war Southern states.

The Black Codes attempted to return ex-slaves to something like their former condition by, among other things, restricting their movement, forcing them to enter into year-long labor contracts, prohibiting them from owning firearms, and by preventing them from suing or testifying in court.

In his veto message, he objected to the measure because it conferred citizenship on the freedmen at a time when 11 out of 36 states were unrepresented in the Congress, and that it allegedly discriminated in favor of African Americans and against whites.

[11][12] The experience encouraged both radical and moderate Republicans to seek Constitutional guarantees for black rights, rather than relying on temporary political majorities.

[13] On June 18, 1866, Congress adopted the Fourteenth Amendment, which guaranteed citizenship and equal protection under the laws regardless of race, and sent it to the states for ratification.

[14] Section 2 of the Fourteenth Amendment punished, by reduced representation in the House of Representatives, any state that disenfranchised any male citizens over 21 years of age.

By failing to adopt a harsher penalty, this signaled to the states that they still possessed the right to deny ballot access based on race.

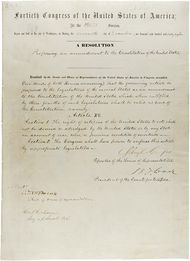

[23] A House and Senate conference committee proposed the amendment's final text, which banned voter restriction only on the basis of "race, color, or previous condition of servitude.

"[3] To attract the broadest possible base of support, the amendment made no mention of poll taxes or other measures to block voting, and did not guarantee the right of blacks to hold office.

[32] Some Radical Republicans, such as Massachusetts Senator Charles Sumner, abstained from voting because the amendment did not prohibit literacy tests and poll taxes.

[27] Though many of the original proposals for the amendment had been moderated by negotiations in committee, the final draft nonetheless faced significant hurdles in being ratified by three-fourths of the states.

[25] However, with the passage of the Fourteenth Amendment, which had explicitly protected only male citizens in its second section, activists found the civil rights of women divorced from those of blacks.

[26] Newly elected President Ulysses S. Grant strongly endorsed the amendment, calling it "a measure of grander importance than any other one act of the kind from the foundation of our free government to the present day."

He privately asked Nebraska's governor to call a special legislative session to speed the process, securing the state's ratification.

[21] In April and December 1869, Congress passed Reconstruction bills mandating that Virginia, Mississippi, Texas and Georgia ratify the amendment as a precondition to regaining congressional representation; all four states did so.

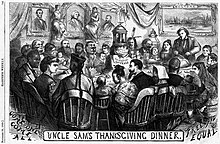

[43]African Americans called the amendment the nation's "second birth" and a "greater revolution than that of 1776", according to historian Eric Foner in his book The Second Founding: How the Civil War and Reconstruction Remade the Constitution.

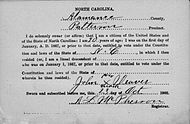

[45] In United States v. Reese (1876),[46] the first U.S. Supreme Court decision interpreting the Fifteenth Amendment, the Court interpreted the amendment narrowly, upholding ostensibly race-neutral limitations on suffrage, including poll taxes, literacy tests, and a grandfather clause that exempted citizens from other voting requirements if their grandfathers had been registered voters.

As president, he refused to enforce federal civil rights protections, allowing states to begin to implement racially discriminatory Jim Crow laws.

[52] In Ex Parte Yarbrough (1884), the Court allowed individuals who were not state actors to be prosecuted because Article I, Section 4, gives Congress the power to regulate federal elections.

Along with increasing legal obstacles, blacks were excluded from the political system by threats of violent reprisals by whites in the form of lynch mobs and terrorist attacks by the Ku Klux Klan.

[51] In Guinn v. United States (1915),[55] a unanimous Court struck down an Oklahoma grandfather clause that effectively exempted white voters from a literacy test, finding it to be discriminatory.

[62][63] However, in United States v. Classic (1941),[64] the Court ruled that primary elections were an essential part of the electoral process, undermining the reasoning in Grovey.

Based on Classic, the Court in Smith v. Allwright (1944),[65] overruled Grovey, ruling that denying non-white voters a ballot in primary elections was a violation of the Fifteenth Amendment.

[66] In the last of the Texas primary cases, Terry v. Adams (1953),[67] the Court ruled that black plaintiffs were entitled to damages from a group that organized whites-only pre-primary elections with the assistance of Democratic party officials.