Fifty Grand

"Fifty Grand" tells the story of Jack Brennan as he trains for and boxes in his fight with challenger Jimmy Walcott.

Jack Brennan, the current welterweight champion, is at Danny Hogan's New Jersey training camp (called the "health farm" throughout the story) struggling to get in shape for his upcoming fight with favorite Jimmy Walcott.

Jack is not optimistic about the fight and does not adjust to life at the health farm; "He didn't like being away from his wife and the kids and he was sore and grouchy most of the time," Doyle reports.

That afternoon John Collins, Jack's manager, drives to the health farm with two well-dressed men named Steinfelt and Morgan.

Later that evening, he drinks heavily and suggests Doyle put money on Walcott, confiding that he himself has bet "fifty grand" on the opposing boxer.

"[1] Years before writing "Fifty Grand", Hemingway wrote a boxing story which appeared in the April 1916 edition of Oak Park High School's literary magazine Tabula.

This story, called "A Matter of Colour", was more obviously comical than "Fifty Grand", but the two bear several similarities, such as a non-protagonist narrator and a "trickster out-tricked" theme.

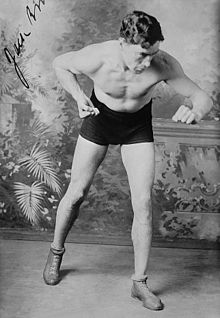

[2] Though authors today seldom write about boxing, stories like "Fifty Grand" were common and popular in the late 19th and early 20th century.

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle also wrote several stories about boxing, such as Rodney Stone and The Croxley Master, and made his famous Sherlock Holmes an amateur boxer.

[4] Hemingway, unable to remove anything from the story, allowed writer Manuel Komroff to cut it for him, but found his efforts unsatisfactory.

[4] The story finally appeared in the July 1927 issue of The Atlantic Monthly, under Ellery Sedgwick's owner-editorship, after Fitzgerald persuaded Hemingway to remove the first three pages, arguing that the Britton-Leonard fight they alluded to was too well known.

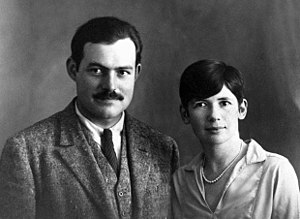

According to Philip G. and Rosemary R. Davies, Hemingway seems to have based the story on the 1 November 1922 welterweight championship fight between Jack Britton and Mickey Walker.

'"[3] Martine adds, "If a man standing at ringside in a photo of the knockdown is not Hemingway, one critic has offered to eat the New York Times September 26, 1922, p. 14, and the rest of the paper.

Fenton noted in 1952 that Jack fits the ideals of a professional, showing the ability to think and commitment to and knowledge of his sport.

His skill and craftsmanship in the ring stands in stark contrast to the brute strength and crude force employed by the slower, heavier Walcott.

"[3] Philip G. and Rosemary R. Davies read Jack as a code hero, whose courage is partly obscured by the facts of the Britton–Walker fight on which they believe Hemingway based the story.

"Brennan's courage, while real, cannot reverse the impression created by the bulk of the story", they write, unable to find Jack admirable until the final pages.

[5] They argue that Hemingway tried to show Jack's courage by giving him motives other than the obvious monetary one—they cite the statement, "His money was all right and now he wanted to finish it off right to please himself.

Even with the humor at both boxers' expense, he concludes that "Jack has done much more than protect his fifty grand; he has, through his quickwittedness and stoicism, prevailed without loss of his self-respect.

"[9] It may also be possible that Steinfelt and Morgan also organized for Walcott to throw the match with the low blow, as John reveals "They certainly tried a nice double-cross."

"[10] However, some critics—among them Wilson Lee Dodd, whose article entitled "Simple Annals of the Callous" appeared in the Saturday Review of Literature—found Hemingway's subjects lacking.

Joseph Wood Krutch called the stories in Men Without Women "Sordid little catastrophes" involving "very vulgar people.

(All very much alike, weariness too great, sordid small catastrophes, stack the cards on fate, very vulgar people, annals of the callous, dope fiends, soldiers, prostitutes, men without a gallus)[12]