Great Fire of London

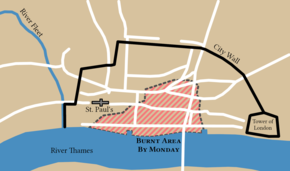

The use of the major firefighting technique of the time, the creation of firebreaks by means of removing structures in the fire's path, was critically delayed due to the indecisiveness of the Lord Mayor, Sir Thomas Bloodworth.

The fears of the homeless focused on the French and Dutch, England's enemies in the ongoing Second Anglo-Dutch War; these substantial immigrant groups became victims of street violence.

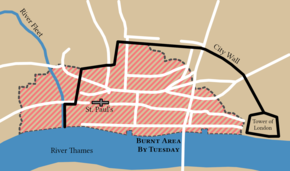

On Tuesday, the fire spread over nearly the whole city, destroying St Paul's Cathedral and leaping the River Fleet to threaten Charles II's court at Whitehall Palace.

The battle to put out the fire is considered to have been won by two key factors: the strong east wind dropped, and the Tower of London garrison used gunpowder to create effective firebreaks, halting further spread eastward.

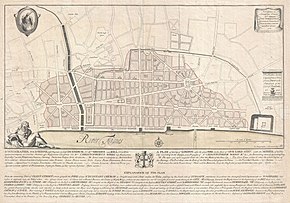

[17] The only major area built with brick or stone was the wealthy centre of the city, where the mansions of the merchants and brokers stood on spacious lots, surrounded by an inner ring of overcrowded poorer parishes, in which all available building space was used to accommodate the rapidly growing population.

Charles's next, sharper message in 1665 warned of the risk of fire from the narrowness of the streets and authorised both imprisonment of recalcitrant builders and demolition of dangerous buildings.

The Thames offered water for firefighting and the chance of escape by boat, but the poorer districts along the riverfront had stores and cellars of combustibles which increased the fire risk.

This drastic method of creating firebreaks was increasingly used towards the end of the Great Fire, and modern historians believe that this in combination with the wind dying down was what finally won the struggle.

[47][48] Jacob Field notes that although Bloodworth "is frequently held culpable by contemporaries (as well as some later historians) for not stopping the Fire in its early stages... there was little [he] could have done" given the state of firefighting expertise and the sociopolitical implications of antifire action at that time.

[52] Pepys found Bloodworth trying to coordinate the fire-fighting efforts and near to collapse, "like a fainting woman", crying out plaintively in response to the King's message that he was pulling down houses: "But the fire overtakes us faster than we can do it."

[62] The houses of the bankers in Lombard Street began to burn on Monday afternoon, prompting a rush to rescue their stacks of gold coins before they melted.

[66][67] John Evelyn, courtier and diarist, wrote: The conflagration was so universal, and the people so astonished, that from the beginning, I know not by what despondency or fate, they hardly stirred to quench it, so that there was nothing heard or seen but crying out and lamentation, running about like distracted creatures without at all attempting to save even their goods, such a strange consternation there was upon them.

He observed a great exodus of carts and pedestrians through the bottleneck City gates, making for the open fields to the north and east, "which for many miles were strewed with moveables of all sorts, and tents erecting to shelter both people and what goods they could get away.

Fear and suspicion hardened into certainty on Monday, as reports circulated of imminent invasion and of foreign undercover agents seen casting "fireballs" into houses, or caught with hand grenades or matches.

[75] Suspicions rose to panic and collective paranoia on Monday, and both the Trained Bands and the Coldstream Guards focused less on fire fighting and more on rounding up foreigners and anyone else appearing suspicious, arresting them, rescuing them from mobs, or both.

[84] "The Duke of York hath won the hearts of the people with his continual and indefatigable pains day and night in helping to quench the Fire," wrote a witness in a letter on 8 September.

[85] On Monday evening, hopes were dashed that the massive stone walls of Baynard's Castle, Blackfriars would stay the course of the flames, the western counterpart of the Tower of London.

[87] The Duke of York's command post at Temple Bar, where Strand meets Fleet Street, was supposed to stop the fire's westward advance towards the Palace of Whitehall.

[92] Through the day, the flames began to move eastward from the neighbourhood of Pudding Lane, straight against the prevailing east wind and towards the Tower of London with its gunpowder stores.

[94] Everybody had thought St. Paul's Cathedral a safe refuge, with its thick stone walls and natural firebreak in the form of a wide empty surrounding plaza.

Evelyn was horrified at the numbers of distressed people filling it, some under tents, others in makeshift shacks: "Many [were] without a rag or any necessary utensils, bed or board ... reduced to extremest misery and poverty.

Food production and distribution had been disrupted to the point of non-existence; Charles announced that supplies of bread would be brought into the City every day, and markets set up round the perimeter.

Surging into the streets, the frightened mob fell on any foreigners whom they happened to encounter, and were pushed back into the fields by the Trained Bands, troops of Life Guards, and members of the court.

[1] Field argues that the number "may have been higher than the traditional figure of six, but it is likely it did not run into the hundreds": he notes that the London Gazette "did not record a single fatality" and that had there been a significant death toll it would have been reflected in polemical accounts and petitions for charity.

[115] Charles II encouraged the homeless to move away from London and settle elsewhere, immediately issuing a proclamation that "all Cities and Towns whatsoever shall without any contradiction receive the said distressed persons and permit them the free exercise of their manual trades".

[127] On 5 October, Marc Antonio Giustinian, Venetian Ambassador in France, reported to the Doge of Venice and the Senate, that Louis XIV announced that he would not "have any rejoicings about it, being such a deplorable accident involving injury to so many unhappy people".

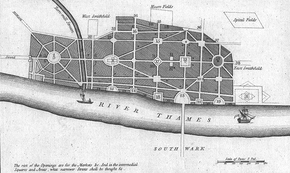

According to archaeologist John Schofield, Wren's plan "would have probably encouraged the crystallisation of the social classes into separate areas", similar to Haussmann's renovation of Paris in the mid-1800s.

[148] Despite these factors, London retained its "economic pre-eminence" because of the access to shipping routes and its continued central role in political and cultural life in England.

[119] Allegations that Catholics had started the fire were exploited as powerful political propaganda by opponents of pro-Catholic Charles II's court, mostly during the Popish Plot and the exclusion crisis later in his reign.

[158][157] On Charles' initiative, a Monument to the Great Fire of London was erected near Pudding Lane, designed by Christopher Wren and Robert Hooke, standing 61+1⁄2 metres (202 ft) tall.