First-move advantage in chess

[1] Some players, including world champions such as José Raúl Capablanca, Emanuel Lasker, Bobby Fischer, and Vladimir Kramnik, have expressed fears of a "draw death" as chess becomes more deeply analyzed, and opening preparation becomes ever more important.

To alleviate this danger, Capablanca, Fischer, and Kramnik proposed chess variants to revitalize the game, while Lasker suggested changing how draws and stalemates are scored.

Several of these suggestions have been tested with engines: in particular, Larry Kaufman and Arno Nickel's extension of Lasker's idea – scoring being stalemated, bare king, and causing a threefold repetition as quarter-points – shows by far the greatest reduction of draws among the options tested, and Fischer random chess (which obviates preparation by randomising the starting array) has obtained significant uptake at top level.

"[2][3] Two decades later, statistician Arthur M. Stevens concluded in The Blue Book of Charts to Winning Chess, based on a survey of 56,972 master games that he completed in 1967, that White scores 59.1%.

In 2005, Grandmaster (GM) Jonathan Rowson wrote that "the conventional wisdom is that White begins the game with a small advantage and, holding all other factors constant, scores approximately 56% to Black's 44%".

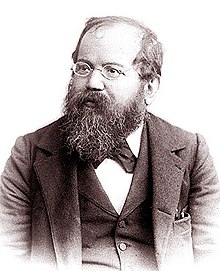

[35] Steinitz, the first World Champion, who is widely considered the father of modern chess,[36][37][38] wrote in 1889, "It is now conceded by all experts that by proper play on both sides the legitimate issue of a game ought to be a draw.

[40][41][42] Reuben Fine, one of the world's leading players from 1936 to 1951,[43] wrote that White's opening advantage is too intangible to be sufficient for a win without an error by Black.

[71] Fourteenth World Champion Vladimir Kramnik agreed, writing: "From my own experience, I know how difficult it has become to force a complex and interesting fight if your opponent wants to play it safe.

As soon as one side chooses a relatively sterile line of play, the opponent is forced to follow suit, leading to an unoriginal game and an inevitably drawish outcome.

)[75] Kaufman does concede that this is a "much more extreme idea" than simply penalising perpetual check (which is more like the East Asian rules), but argues for it nonetheless because engine-play experiments show that most repetition draws occur when any other move would lead to a position that is not clearly drawn.

Kaufman and Nickel thus argue that this last extension of Lasker's rule "is the simplest and most acceptable way to reduce draws dramatically without fundamentally changing the game.

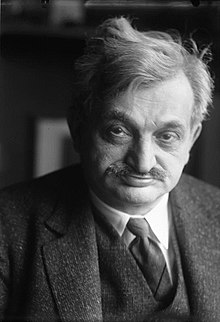

In 1928, Max Euwe (who later became the fifth World Champion) replied to Capablanca's proposal to the effect that he thought that changes were unnecessary, but that he was in agreement with Lasker and Réti that reevaluating stalemate and considering bare king as a victory "would do the game no harm".

Thus Kaufman calls this solution "terrible", going against "the very nature of the game": he writes that "The inferior side should be trying to draw, and to penalize Black for obtaining a good result is crazy.

[84] He writes: "The chess analogue would perhaps be to count pawn 3, knight 10, bishop 11, rook 16, queen 31 in case of a draw by normal rules, with Black winning ties.

[85] Kaufman has also mentioned the old Japanese variant chu shogi (played on a 12×12 board with 46 pieces per side) as a case where draws or opening theory should not be a problem.

[14] More recently, IM Hans Berliner, a former World Champion of Correspondence Chess, claimed in his 1999 book The System that 1.d4 gives White a large, and possibly decisive, advantage.

Starting from 2004, GM Larry Kaufman has expressed a more nuanced view than Adams and Berliner, arguing that the initiative stemming from the first move can always be transformed into some sort of enduring advantage, albeit not a decisive one.

Kaufman writes that "once White makes one or two second-rate moves I start to look for a black advantage",[103] which is similar to the view offered by the 1786 Traité des Amateurs.

"[110] Rowson writes that Adorján's "contention is one of the most important chess ideas of the last two decades ... because it has shaken our assumption that White begins the game with some advantage, and revealed its ideological nature".

"[114] In 2021, Kaufman noted that the number of openings considered playable at the top level has shrunk further, because engines have shown that space advantages are worth more than had been previously supposed: consequently, he writes that "many defenses formerly considered to be playable, if slightly worse for Black, are now viewed as practically, if not theoretically, losing to a well prepared opponent", listing the King's Indian Defense as an example.

Kaufman wrote in 2004 that White's "only serious [tries] for advantage in the opening" are 1.e4 and the Queen's Gambit (by which he means playing d4 and c4 in the first few moves, thus also including diverse Black responses like the King's Indian, the Nimzo-Indian, the Modern Benoni, and the Grünfeld).

"[120] Likewise, Watson surmised that Kasparov, when playing Black, bypasses the question of whether White has an opening advantage "by thinking in terms of the concrete nature of the dynamic imbalance on the board, and seeking to seize the initiative whenever possible".

"[128] Third, some players are able to use the initiative to "play a kind of powerful 'serve and volley' chess in which Black is flattened with a mixture of deep preparation and attacking prowess."

"[134] Rowson also notes that Black's chances increase markedly by playing good openings, which tend to be those with flexibility and latent potential, "rather than those that give White fixed targets or that try to take the initiative prematurely."

"[136] Watson remarks, "Black's goal is to remain elastic and flexible, with many options for his pieces, whereas White can become paralyzed at some point by the need to protect against various dynamic pawn breaks.

"[148] To explain this paradox, Watson discusses several different reversed Sicilian lines, showing how Black can exploit the disadvantages of various "extra" moves for White.

White is supposed to try for more than just obtaining a comfortable game in reversed colour opening set-ups, and, as the statistics show—surprisingly for a lot of people, but not for me—White doesn't even score as well as Black does in the same positions with his extra tempo and all.

"[183] In symmetrical positions, as the Hodgson–Arkell and Portisch–Tal games discussed below illustrate, Black can continue to imitate White as long as he finds it feasible and desirable to do so, and deviate when that ceases to be the case.

[184][185] On a guest appearance of the Lex Friedman Podcast in October 2022, grandmaster and current number-two classical chess player Hikaru Nakamura believes that Black can maintain sufficient symmetry to force a draw with perfect play.

[208] (If there is no increment, then difficult questions arise when players must try to flag in trivial draws,[208] which happened in the Women's World Chess Championship 2008 in the match between Monika Soćko and Sabina-Francesca Foisor.