First Battle of Algeciras

Both sides had suffered severe damage and casualties, but both were also aware that the battle would inevitably be rejoined and so the aftermath of the British defeat was one of frenzied activity at Gibraltar, Algeciras and Cadiz.

As a result, the British Royal Navy became dominant in the Mediterranean Sea and imposed blockades on French and Spanish ports in the region, including the important naval bases of Toulon and Cadiz.

[4] From there the combined fleet, bolstered by 1,500 French troops under General Pierre Devaux on Linois's ships,[5] could launch major operations against British forces or those of their allies: attacks on Egypt and Lisbon were both suggested, although no firm plan had been drawn up for either.

There Linois was informed by Captain Lord Cochrane, captured in his brig HMS Speedy on 4 July, that a powerful squadron of seven British ships of the line were stationed off Cadiz under Rear-Admiral Sir James Saumarez.

[6] At Gibraltar, the only ship in harbour was the small sloop-of-war HMS Calpe under Captain George Dundas, who on sighting the French squadron immediately sent word to Saumarez off Cadiz.

However, after hearing an inaccurate report from an American merchant ship that Linois had already sailed from Algeciras, Keats reasoned that the French would have turned eastwards for Toulon and thus he would be too late to catch them.

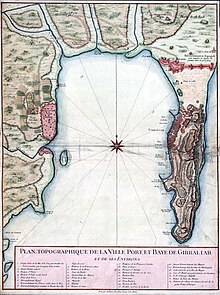

[9] The southern approach to the harbour was covered by three gunboats and batteries at Fort Santa Garcia and Torre de la Vila Vega on the shore and the fortified island of Isla Verda, which mounted seven heavy cannon, lay between Indomptable and Muiron.

[10] Further support was offered by more distant forts that could land shells in the anchorage and most importantly by the geography of the bay, which was scattered with complicated shoals and rocks that made navigation difficult for unfamiliar sailors.

On sighting the British squadron, Linois gave orders for the French ships to warp into the shallower waters along the shoreline, and many sailors and soldiers aboard were despatched to assist the Spanish gun batteries around the bay.

[16] The French and Spanish responded with a heavy cannonade against the anchored ships, the engagement lasting half an hour until Formidable temporarily ceased firing and began to slowly warp further inshore.

[17] Assistance was provided by Dundas in Calpe, who took his small vessel inshore to engage the Spanish batteries firing on the British squadron,[13] and also attacked the frigate Muiron at close range.

[18] At 09:15 the straggling rear of the British squadron began to arrive, led by the flagship HMS Caesar, which anchored ahead of Audacious and inshore of Venerable before opening fire on Desaix.

[21] Hannibal was now isolated at the northern end of the British line, under heavy fire from Formidable as well as the Spanish shore batteries and gunboats and unable to manoeuvre or effectively respond.

[22] Saumarez responded by cutting his cables on Caesar and wearing past the becalmed Audacious and Venerable, taking up station off Indomptable's vulnerable bows and repeatedly raking the stranded ship.

Both Caesar and Audacious were now directly exposed however to the heavy fire from Isla Verda, the batteries there and all around the bay now manned by French sailors who had evacuated the grounded ships of the line.

[22] Venerable's masts and rigging had been so badly torn by this stage of the battle that Hood was no longer able to effectively manoeuvre in the fitful breeze, although he did eventually pull his ship within range.

[18] To the north of this engagement, the trapped Pompée and Hannibal were under heavy fire from the anchored Formidable and an array of Spanish batteries and gunboats, both ships taking severe damage without being able to effectively reply as their main broadsides now faced away from the enemy.

[22] Pompée was already well on the way thanks to the towing boats, and Caesar and Audacious were able to cut their remaining anchors and limp out of the bay with the assistance of a sudden land breeze that carried them rapidly out of reach of the French and Spanish guns.

[23] French and Spanish soldiers then stormed the ship, and Hannibal's surgeon later reported that a number of wounded men were trampled to death as the boarding parties sought to extinguish the fires.

[25] Captain Dundas, who had watched the entire battle from Gibraltar, believed on seeing the flag that it meant that Ferris was still holding out on Hannibal and requesting either support to salvage his battered ship or for it to be evacuated before surrendering.

[27] The British crews had found during the engagement that their gunnery was affected by the lack of wind, much of their shot flying over the French ships and into the town of Algeciras, which was considerably damaged.

Urged by French Counter-Admiral Pierre Dumanoir le Pelley, who was in Cadiz to take occupation of the promised six ships of the line, Mazzaredo ordered Vice-Admiral Juan Joaquin de Moreno [es] to sail with a formidable force which arrived off Algeciras Bay on 9 July.

[38] Historian Richard Gardiner commented that "The well trained and led French had fought hard and skillfully and a combination of weather, luck and shore support had given them the victory against a superior force of which they had captured one.