Atlantic U-boat campaign of World War I

This campaign was highly destructive, and resulted in the loss of nearly half of Britain's initial merchant marine fleet during the course of the war.

While the operation was a failure, it caused the Royal Navy some uneasiness, disproving earlier estimates as to U-boats' radius of action and leaving the security of the Grand Fleet's unprotected anchorage at Scapa Flow open to question.

On the other hand, the ease with which U-15 had been destroyed by Birmingham encouraged the false belief that submarines were no great danger to surface warships.

[citation needed] On 5 September 1914, U-21 commanded by Lieutenant Otto Hersing made history when he torpedoed the Royal Navy light cruiser HMS Pathfinder.

Early in the morning of that day, a lookout on the bridge of U-9, commanded by Lieutenant Otto Weddigen, spotted a vessel on the horizon.

At closer range, Weddigen discovered three old Royal Navy armoured cruisers, HMS Aboukir, Cressy, and Hogue.

These three vessels were not merely antiquated, but were staffed mostly by reservists, and were so clearly vulnerable that a decision to withdraw them was already filtering up through the bureaucracy of the Admiralty.

This, in a sense, was a more significant victory than sinking a few old cruisers; the world's most powerful fleet had been forced to abandon its home base.

On 23 November U-18 penetrated Scapa Flow via Hoxa Sound, following a steamer through the boom and entering the anchorage with little difficulty.

U-18 then suffered a failure of her diving plane motor and the boat became unable to maintain her depth, at one point even impacting the seabed.

[8] The C-in-C Channel Fleet, Adm. Sir Lewis Bayly, was criticized for not taking proper precautions during the exercises, but was cleared of the charge of negligence.

The operation was performed broadly in accordance with the cruiser rules, the crew being ordered into the lifeboats before Glitra was sunk by having her seacocks opened.

[citation needed] Less than a week later, on 26 October, U-24 became the first submarine to attack an unarmed merchant ship without warning, when she torpedoed the steamship Admiral Ganteaume, with 2,500 Belgian refugees aboard.

[9] On 30 January 1915, U-20, commanded by Kapitänleutnant Otto Dröscher, torpedoed and sank the steamships Ikaria, Tokomaru and Oriole without warning, and on 1 February fired a torpedo at, but missed, the hospital ship Asturias, despite her being clearly identifiable as a hospital ship by her white paintwork with green bands and red crosses.

[14] These incidents caused outrage amongst neutrals and the scope of the unrestricted campaign was scaled back in September 1915 to lessen the risk of those nations entering the war against Germany.

The most effective defensive measures proved to be advising merchantmen to turn towards the U-boat and attempt to ram, forcing it to submerge.

[citation needed] There were no means to detect submerged U-boats, and attacks on them were limited to efforts to damage their periscopes with hammers and dropping guncotton bombs.

A further series of operations, in August and October 1916, were similarly unfruitful, and the strategy was abandoned in favour of resuming commerce warfare.

Renewed orders in October suggested that unrestricted submarine warfare may come at some point in the future, but commerce attacks had to operate under cruiser rules for now.

[25][26] According to German estimates, Scheer's intransigence cost Germany the opportunity to sink 1.6 to 3 million tons of Allied shipping.

In the three months following their introduction, on the Atlantic, North Sea, and Scandinavian routes, of 8,894 ships convoyed just 27 were lost to U-boats.

1917 and 1918 saw a series of attacks on hospital ships, which generally sailed fully lit, to show their non-combatant status.

[31] Commanded by Wilhelm Werner, U-55 also deliberately drowned dozens of crewmen who had survived the sinkings of the cargo ships Torrington in April 1917 and Belgian Prince in June 1917.

[34] The convoy system was effective in reducing allied shipping losses, while better weapons and tactics made the escorts more successful at intercepting and attacking U-boats.

The Flanders boats still tried to use the route, but continued to suffer losses, and after March switched their operations to Britain's east coast.

On 11 May, U-86 sank one of a pair of ships detached from a convoy in the Channel, but the next day an attack on the troopship RMS Olympic led to the destruction of U-103, while UB-72 was sunk by British submarine HMS D4.

[40] During the summer, the extension of the convoy system and effectiveness of the escorts made the east coast of Britain as dangerous for the U-boats as the Channel had become.

In October, with the German army in full retreat, the Flanders flotilla was forced to abandon its base at Bruges before it was overrun.

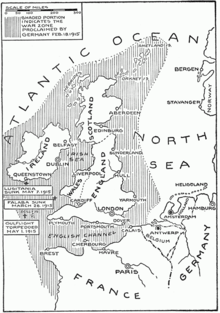

In 1918, the Allies, particularly the US, undertook to create a barrage across the Norwegian Sea, to block U-boat access to the Western Approaches by the north-about route.

This huge undertaking involved laying and maintaining minefields and patrols in deep waters over a distance of 300 nautical miles (556 kilometers).