First Carlist War

[6] Furthermore, various conflicts with the British and especially the Battle of Trafalgar had left the Spanish without the naval strength to maintain healthy maritime trade with the Americas and the Philippines, leading to historically low overseas revenue.

Various conflicts with the British and especially the Battle of Trafalgar had left the Spanish without the naval strength to maintain healthy maritime trade with the Americas and the Philippines, leading to historically low overseas revenue and ability to control the colonies.

[13] Nonetheless, the Spanish government would be overburdened with costs needed to establish control over the country over the following decades—88% of taxes collected in February 1822 went to fund the military—which increased when Ferdinand maintained a French garrison between 1824-1828 "as a Varangian Guard" to ensure his power.

Some historians argue that the Pragmatic Sanction was encouraged in order to please the politically-active liberal financiers,[citation needed] and in fact it was in the interest of loan repayment that the British and French protected the cristinos during the war.

[20] Furthermore, Spain was undergoing a deflationary spiral caused by both the Napoleonic War and the loss of the colonies, which left Spanish producers without the incredibly valuable market to sell their goods to as well as the Mint without the metal crucial to make coins.

The sparseness of population as well as the general predicaments of Spanish labourers resulted in gross mismanagement of arable land[6]and inability of Spain to significantly restart industrial and commercial activity after the Napoleonic War.

He also established a militia called the Voluntarios Realistas ("Royalist Volunteers") which peaked at 284,000 men in 1832 in order to facilitate this suppression, led by an inspector general who answered only to the King himself and funded independently by permanent tax revenues.

[43] Nonetheless, the political situation in Spain was too fragmented for a moderate government like Bermudez's to gain and maintain public support and most of its activity was restrained to controlling potential rebellions from both the Carlists and the liberals.

[citation needed] This Constitution abolished Basque home rule, and in the following years the contrafueros (literally "against fueros") removed provisions such as fiscal sovereignty and specificity of military draft.

[47]Modern historian Mark Lawrence agrees:The Pretender’s foralism was not proactive but purely in reaction to the fact that the rest of Spain (which had long been stripped of its fueros) had failed to rally to his cause.

[51] Coverdale summarised four factors as to why this was so: (1) traditional society was still economically viable for most of population, hence liberalism was seen a threat; (2) natural leadership strata (clergy, landowners) lived cheek by jowl with peasants and supported the Carlist cause; (3) the terrain was sufficiently abrupt and broken to prevent the use of cavalry and to facilitate small bands to escape (to change their shirts and fight another day), whilst the landscape was densely populated enough to allow regular food and supplies; and (4) the appearance of the extremely gifted guerrilla leader, Tomás de Zumalacárregui.

The end of this option during a period of accelerated population growth meant that the Basque region "faced a bottleneck of impoverished and underemployed men of military age who had little [to] lose by joining Carlist insurrections".

[citation needed] The Basque pro-fueros liberal class under the influence of the Enlightenment and ready for independence from Spain (and initially at least allegiance to France) was put down by the Spanish authorities at the end of the War of the Pyrenees (San Sebastián, Pamplona, etc.).

Salvador de Madariaga, in his book Memories of a Federalist (Buenos Aires, 1967), accused the Basque clergy of being "the heart, the brain and the root of the intolerance and the hard line" of the Spanish Catholic Church.[when?

[citation needed] As Paul Johnson has written, "both royalists and liberals began to develop strong local followings, which were to perpetuate and transmute themselves, through many open commotions and deceptively tranquil intervals, until they exploded in the merciless civil war of 1936-39.

[61]However, Henry Bill, another contemporary, wrote that, although "it was mutually agreed upon to treat the prisoners taken on either side according to the ordinary rules of war, a few months only elapsed before similar barbarities were practiced with all their former remorselessness.

"[62] Carlos had refused to openly challenge either the Pragmatic Sanction nor his brother while the latter remained alive, as the "recent legitimist rising knowns as the Agraviados had taught him the wisdom of awaiting events.

[6] Most of these propagandist pamphlets published before the war were printed in France by Carlist exiles who then smuggled them into Spain, and so were most widely distributed in the northern regions of the Basque Country, Navarre, Aragon, and Catalonia.

[76] The growing anti-militarist sentiment amongst the liberals resulted in the emergence in the Napoleonic War amongst the army of a faction that "was hostile to the whole constitutional experiment" due to the "shabby treatment" received from politicians.

[61]However, Henry Bill, another contemporary, wrote that, although "it was mutually agreed upon to treat the prisoners taken on either side according to the ordinary rules of war, a few months only elapsed before similar barbarities were practiced with all their former remorselessness.

[70] While permanent fortresses placed in vantage points and equipped with artillery were used, guerilla patrols and armed farmers often served to control remote hilltops and roads between villages and cities.

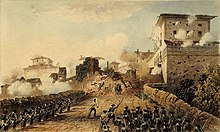

[70] The war was long and hard, and the Carlist forces (labeled "the Basque army" by John F. Bacon) achieved important victories in the north under the direction of the brilliant general Tomás de Zumalacárregui.

In December, Valdes's focus on Navarre allowed the Carlists in the other Basque provinces to regroup as the secondary units he left behind only patrolled the main roads and garrisoned the principal towns of the region.

[85] In summer 1834, Liberal (Isabeline) forces set fire to the Sanctuary of Arantzazu and a convent of Bera, while Zumalacárregui showed his toughest side when he had volunteers refusing to advance over Etxarri-Aranatz executed.

The Carlist cavalry engaged and defeated in Viana an army sent from Madrid (14 September 1834), while Zumalacárregui's forces descended from the Basque Mountains over the Álavan Plains (Vitoria), and prevailed over general Manuel O'Doyle.

The veteran general Espoz y Mina, a Liberal Navarrese commander, attempted to drive a wedge between the Carlist northern and southern forces, but Zumalacárregui's army managed to hold them back (late 1834).

In January, the liberal government of Francisco Martínez de la Rosa successfully narrowly defeated an attempted military coup d'état and then faced urban uprisings in Málaga, Zaragoza, and Murcia in the spring.

[89] In January, the Carlists took over Baztan in an operation where the general Espoz y Mina narrowly escaped a severe defeat and capture, while the local Liberal Gaspar de Jauregi Artzaia ('the Shepherd') and his chapelgorris were neutralized in Zumarraga and Urretxu.

An English commentator wrote that "it was at Majaciete that [Narváez] rescued Andalucía from the Carlist invasion by a brilliant coup de main, in a rapid but destructive action, which will not readily be effaced from the memory of the southern provinces.

[93]Paul Johnson agrees with the characterization, writing "both royalists and liberals began to develop strong local followings, which were to perpetuate and transmute themselves, through many open commotions and deceptively tranquil intervals, until they exploded in the merciless civil war of 1936-39.