International Workingmen's Association

Among the many European radicals were English Owenites, followers of Pierre-Joseph Proudhon and Louis Auguste Blanqui, Irish and Polish nationalists, Italian republicans and German socialists.

Most of the British members of the committee were drawn from the Universal League for the Material Elevation of the Industrious Classes[6] and were noted trade-union leaders like Odger, George Howell (former secretary of the London Trades Council, which itself declined affiliation to the IWA, although remaining close to it), Cyrenus Osborne Ward and Benjamin Lucraft and included Owenites and Chartists.

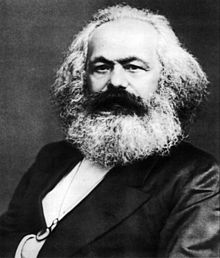

[7] This executive committee in turn selected a subcommittee to do the actual writing of the organisational programme—a group which included Marx and which met at his home about a week after the conclusion of the St. Martin's Hall assembly.

[5] This subcommittee deferred the task of collective writing in favour of sole authorship by Marx and it was he who ultimately drew up the fundamental documents of the new organisation.

After the Paris Commune (1871), Bakunin characterised Marx's ideas as authoritarian and argued that if a Marxist party came to power its leaders would end up as bad as the ruling class they had fought against (notably in his Statism and Anarchy).

In 1874, Marx wrote some decisive notes rebutting Bakunin's affirmations on this book, referring to them as mere political rhetoric without a theory of the State and without the knowledge about social class struggles and the economic factor.

On the opposing side, the anarchists, who held complete control of the working-class movement in Spain, persistently tried to recruit Portuguese socialists to the Alliance.