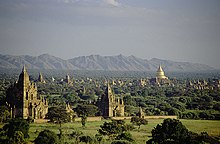

First Mongol invasion of Burma

The invasions ushered in 250 years of political fragmentation in Burma and the rise of ethnic Tai-Shan states throughout mainland Southeast Asia.

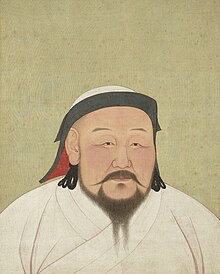

After a brief lull, Kublai Khan in 1281 again turned his attention to Southeast Asia, demanding tribute from Pagan, the Khmer Empire, Đại Việt and Champa.

Two dry season campaigns (1283–1285) later, the Mongols had occupied down to Tagaung and Hanlin, forcing the Burmese king to flee to Lower Burma.

[4] Between the newly conquered Mongol territory and Pagan were a wide swath of borderlands stretching from present-day Dehong, Baoshan and Lincang prefectures in Yunnan as well as the Wa and Palaung regions (presumably in present-day northern Shan State),[note 2] which Pagan and Dali had both claimed and exercised overlapping spheres of influence.

For the next dozen years, they consolidated their hold over the newly conquered land, which not only provided them with a base from which to attack the Song from the rear but also was strategically located on the trade routes from China to Burma and India.

The Mongols set up military garrisons, manned mostly by Turkic-speaking Muslims from Central Asia, in 37 circuits of the former Dali Kingdom.

The crown had lost resources needed to retain the loyalty of courtiers and military servicemen, inviting a vicious circle of internal disorders and external challenges.

The letter says:[12]"If you have finally decided to fulfill your duties towards the All-Highest, send one of your brothers or senior ministers, to show men that all the world is linked with Us, and enter into a perpetual alliance.

[14] Meanwhile, in 1274, the former Dali Kingdom was officially reorganized as the province of Yunnan, with Sayyid Ajjal Shams al-Din Omar as governor.

Just coming off a disastrous Japanese campaign, the emperor was unwilling to commit the central government troops to what he considered a low priority affair.

[note 5] Like in 1272, the Burmese government responded by sending an army to reclaim the rebellious state; but unlike in 1272, the Mongols had posted a sizable garrison there.

"[17][19] Even then, the 40,000 to 60,000 figures of the Burmese army strength were likely eye estimates and may still be too high; the Mongols may have erred "on the side of generosity" not to "diminish their glory in defeating superior numbers.

"[20] According to Marco Polo's account, in the early stages of the battle, the Turkish and Mongol horsemen "took such fright at the sight of the elephants that they would not be got to face the foe, but always swerved and turned back," while the Burmese forces pressed on.

But the Mongol commander Huthukh[note 9] did not panic; he ordered his troops to dismount, and from the cover of the nearby treelines, aim their bows directly at the advancing elephants.

In the following dry season of 1277–1278, c. December 1277, a Mongol army of 3,800 men led by Nasr al-Din, son of Gov.

Pagan did not relinquish its claim to the frontier regions, and the Burmese, apparently taking advantage of Mongol preoccupations elsewhere, rebuilt their forts at Kaungsin and Ngasaunggyan later in 1278, posting permanent garrisons commanded by Einda Pyissi.

The Burmese king was to send his ten senior ministers accompanied by one thousand cavalry officers to the emperor's court.

[26] At least one army consisted of 14,000 men of the erstwhile Khwarezmid Empire under the command of Yalu Beg was sent to Yunnan to reinforce the Burma invasion force, which again was made up of Turks and other central Asians.

Prince Sangqudar was the commander-in-chief of the invasion force; his deputies were Vice Governor Taipn, and commander Yagan Tegin.

A usurper named Wareru seized the southern port city of Martaban (Mottama) by killing its Pagan-appointed governor.

[5][29] The two sides had reached a tentative agreement by 3 March 1286,[note 12] which calls for a full submission of the Pagan Empire, and central Burma to be organized as the province of Mianzhong (Chinese: 緬中; Wade–Giles: Mien-Chung).

The Burmese delegation formally acknowledged Mongol suzerainty of their kingdom, and agreed to pay annual tribute tied to the agricultural output of the country.

The Mongol army commanded by Prince Ye-sin Timour, a grandson of the emperor, marched south toward Pagan.

[29] According to mainstream traditional (colonial-era) scholarship, the Mongol army ignored the imperial orders to evacuate; fought its way down to Pagan with the loss of 7000 men; occupied the city; and sent out detachments to receive homage, one of which reached south of Prome.

[41][42] They were held at bay by the Burmese defenses led by commanders Athinkhaya, Yazathingyan and Thihathu, and probably never got closer than 160 km north of Pagan.

To check their rising power, Kyawswa submitted to the Mongols in January 1297, and was recognized by the Yuan emperor Temür Khan as King of Pagan on 20 March 1297.

Two years later, on 4 April 1303, the Mongols abolished the province of Zhengmian (Cheng-Mien), evacuated Tagaung, and returned to Yunnan.

The invasions ushered in a period of political fragmentation, and the rise of Tai-Shan states throughout mainland Southeast Asia.

[note 13] The vast region surrounding the Irrawaddy valley would continue to be made up of several small Tai-Shan states well into the 16th century.

[55][56]) From a geopolitical standpoint, the Mongol–Chinese presence in Yunnan pushed the Shan migrations in the direction of Burma (and parts of the Khmer Empire).