First Report on the Public Credit

[8] During the American Revolution, the Continental Congress, under the Articles of Confederation, amassed huge war debts but lacked the power to service these obligations by tariffs or other taxation.

[9] When the state legislatures failed to meet quotas for war material by local taxation, Patriot armies turned to confiscating supplies from farmers and tradesmen, compensating them with IOUs of uncertain value.

[19][20] A consensus arose in Congress for the primary source of revenue to be tariff and tonnage duties,[21][22] which would serve to cover operating expenses for the central government and to pay interest and principal on foreign and domestic debt.

Many of them were combat veterans who, during demobilization in 1783,[13] had been paid in IOUs, "certificates of indebtedness"[33] or "securities" (not to be confused with the worthless Continental currency or bills of credit)[3] and redeemable when the government's fiscal order had been restored.

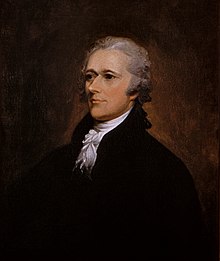

[36] Hamilton rejected both "repudiation" and "discrimination" and championed "redemption," the reserving of payment at full value strictly to the current holders of the certificates, with arrears of interest.

Rather than seeking to liquidate the national debt, Hamilton recommended for government securities to be traded at par to promote their exchange as legal tender equivalent in value to hard currency.

[40] Regular payments of the public debt would allow Congress to increase federal money supply safely, which would stimulate capital investments in agriculture and manufacturing.

[44] Monied speculators, alerted that Congress, under the new Constitution, might provide for payment at face value for certificates, sought to buy up devalued securities for profit and investment.

[48] When the report was made public in January 1790, speculators in Philadelphia and New York sent buyers by ship to southern states to buy up securities before the South became aware of the plan.

Devalued certificates were relinquished by holders at low rates even after the news had been received, which reflected the widely held conviction in the South that the credit and assumption measures would be defeated in Congress.

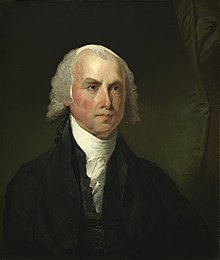

In his address to the House on February 11, 1790, Madison characterized Hamilton's "redemption" as a formula to defraud "battle-worn veterans of the war for independence" [30] and a handout to well-to-do speculators, mostly rich Northerners, including some members of Congress.

[53] His principled opposition to "redemption" was consistent with his view of a federal government designed to shield the less powerful from a majority interest, in this case his agrarian constituency, from Federalist-sponsored economic nationalism.

[57] As Hamilton's plan would greatly simplify and streamline finances, he found Madison's concern over the question of honoring both original and present holders of government securities naïve and counterproductive.

[58] Adopting a much-broader view of the effects of speculation, Hamilton acknowledged that many certificates had been obtained by wealthy individuals, but he considered the "few great fortunes" of minor significance and a "necessary evil" in the transition to sound credit.

"[64] Hamilton confessed years later that "the Federalists have... erred in relying so much on the rectitude and utility of their measures, as to have neglected the cultivation of popular favor, by fair and justifiable expedients.

"[65] Congress rejected Madison's "discrimination" in favor of Hamilton's "redemption" by 36 to 13 in the House of Representatives,[30] which preserved the sanctity of contracts as the cornerstone establishing confidence in public credit.

[36][70] Economically, state securities were vulnerable to local fluctuations in value and thus to speculative buying and selling, activities that would threaten the integrity of a national credit system.

[50][75] Hamilton's funding scheme and "redemption" had won relatively quick approval,[76] but "assumption" was stalled by bitter resistance from southern legislators, led by James Madison.

[88] Intense Congressional debates arose over the "residency question" and resulted in proposals identifying 16 possible sites in competing states, none of which could muster majority support.

[87][89] A number of government officials and state delegations gathered in clandestine meetings and political dinners[90] to resolve the stalled "assumption" bill by linking the "residency" debate to passage of Hamilton's financial program.

[91] Thomas Jefferson, who recently returned from France, where he had acted as a foreign diplomat, understood the practical necessity of Hamilton's fiscal goals establishing America's legitimacy throughout Europe's financial centers.

[92] As the newly appointed Secretary of State, Jefferson invited Hamilton to meet privately with the opposition leader James Madison in an effort to broker a compromise on "assumption" and "residence.

[97] For his part, Hamilton agreed to suppress opposition for the permanent location of the nation's capital at Georgetown on the Potomac, the present site of Washington, DC.

[109] The adoption of Hamilton's report had the immediate effect of converting what had been virtually worthless federal and state certificates of indebtedness to $60 million of funded government securities.