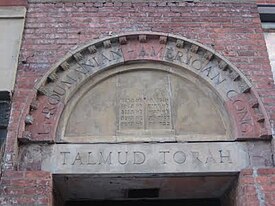

First Roumanian-American Congregation

'Gates of Heaven'), or the Roumanishe Shul[13] (Yiddish for "Romanian synagogue"), was an Orthodox Jewish congregation at 89–93 Rivington Street on the Lower East Side of Manhattan in New York City.

[7] Yossele Rosenblatt, Moshe Koussevitzky, Zavel Kwartin, Moishe Oysher, Jan Peerce and Richard Tucker were all cantors there.

These hardships, combined with an economic depression influenced by low crop yields, resulted in 30 percent of the Jews in Romania emigrating to the United States.

[31] Romanian Jewish immigrants in New York City gravitated to a fifteen-block area bounded by Allen, Ludlow, Houston and Grand streets.

The renovations cost approximately $36,000 (today $1,221,000), and included an entirely new Romanesque Revival facade in the reddish-orange brick that Cady also used on several other churches.

[41] The funds for the purchase were raised from the members of the congregation, and to honor those contributing $10 or more, names were engraved on one of four marble slabs in the stairway to the main sanctuary.

[51] At the meeting Albert Lucas also spoke out strongly against attempts by Christian groups to proselytize Jewish children in nurseries and kindergartens.

[51] Ostensibly to combat this proselytization, in 1903 the congregation was one of several New York City synagogues that allowed Lucas the use of its premises for free religious classes, "open to all children of the neighborhood".

[52] In December 1905 a mass meeting was held at the synagogue to protest massacres of Jews in Russia and mourn their deaths,[53] and the congregation donated $500 to a fund for the sufferers.

[59] At the latter meeting steps were taken to raise $1,000,000 (today $28 million) for oppressed Jews in Romania, and to campaign for their "equal rights and their emancipation from thralldom".

[61] The congregation ran into financial difficulties of its own in 1908, and in October of that year raised funds by selling a number of its Torah scrolls in a public auction.

[25][64] Robinson would later laugh that his propensity for taking the stage was demonstrated when he gave the longest Bar Mitzvah speech in the history of the congregation—"but the men sat still and listened".

[19] Yossele Rosenblatt, Moshe Koussevitzky, Zavel Kwartin and Moishe Oysher all sang there, as did Jan Peerce and Richard Tucker before they became famous opera singers.

[21] Having a reputation for good cantorial singing had a positive impact on a synagogue's finances; congregations depended on the funds from the sale of tickets for seats on the High Holy Days, and the better the cantor, the greater the attendance.

[67] Though his family actually went to a "small storefront synagogue", Buttons was discovered, at age eight, by a talent scout for Rosenblatt's Coopermans Choir, who heard him singing near the intersection of Fifth Street and Avenue C, at a "pickle stand".

[76] In the years following First Roumanian-American's initial purchase and renovation of the Rivington Street building, the congregation made a number of other structural alterations.

[44] On the third floor, centered above the portico, was a similar window, this one flanked by two short recessed twisted columns, each "supporting a stone lintel incised with a cupid's-bow ornament".

[81] The entrance can be seen in the panoramic photograph of the corner of Ludlow and Rivington streets found on the Beastie Boys' 1989 Paul's Boutique album cover foldout.

[71][83] Nevertheless, membership declined during the latter half of the 20th century as the upwardly mobile Jewish population of the Lower East Side moved to north Manhattan, Brooklyn, and the Bronx.

[87] In the early 1990s the congregation could still be assured of the required quorum of ten men for the minyan during the week, as local businessmen attended the morning and evening prayers before opening and after closing their shops.

[47] By 1996, however, the membership was down to around two dozen,[22] and Spiegel began holding services in the small social hall in the basement, as the main sanctuary had become too expensive to maintain.

[91] In the fall of that year Shimon Attie's laser visual work Between Dreams and History was projected onto the synagogue and neighboring buildings for three weeks.

[23][67] Joshua Cohen, writing in The Forward in 2008, described the roof as "falling in respectfully, careful not to disturb the local nightclubs, or the wine and cheesery newly opened across the street".

[97] The National Trust for Historic Preservation issued a press release about the collapse, in which it described "older religious properties, like the First Roumanian-American Synagogue" as "national treasures", and stated: The roof collapse at First Roumanian–American Synagogue this week demonstrates that houses of worship must have access to necessary technical assistance, staff and board training, and the development of new funding sources in order to save these landmarks of spirituality, cultural tradition, and community service.

[96] After a contractor found water damage in the ceiling beams in early December, the three Spiegel brothers had been holding services in their mother Chana's apartment at 383 Grand Street,[29][97] where they placed the congregation's 15 Torah scrolls following the roof cave-in.

[100] Richard Price described the collapsed building in his novel Lush Life,[95] writing that, after the demolition, only the rear wall with a Star of David in stained glass remained:[101] "The candlesticks were standing up in the rubble, and the whole place looked like an experimental stage set—like Shakespeare in the Park.

[102] In a 2008 addendum to his book Dough: A Memoir, Mort Zachter described the remains as "a multimillion dollar real estate opportunity masquerading as a vacant, weed-strewn lot".

[103] The collapse of the roof, and subsequent destruction of the synagogue, generated widespread concern and criticism among preservationists,[6] who blamed Jacob and Shmuel Spiegel—a charge the family rejected.

Julia Vitullo-Martin, senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute and director of its Center for Rethinking Development, stated that First Roumanian-American's roof collapse and subsequent destruction dramatized an "ongoing though undocumented synagogue crisis—particularly in poor neighborhoods" and revealed a broader problem peculiar to Jewish houses of worship: Since Judaism, unlike Catholicism, lacks a hierarchy that could keep track of how many [synagogues] are abandoned and demolished, the breadth of the problem is more difficult to ascertain.

[105]In the years preceding the building's collapse, the congregation had received offers of assistance from the New York Landmarks Conservancy, the National Trust for Historic Preservation, Lower East Side Conservancy, and the New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation, though reports on the amounts and types of assistance offered varied.