First Russian circumnavigation

[6] During the 1780s, growing activity by Great Britain, France, and the United States in the North Pacific, threatened Russian interests in the Far East – notably, the Aleutian Islands where the Chukchi people resisted colonization through force.

[7] On December 22, 1786, Empress Catherine the Great of Russia signed an order directing the Admiralty Board to send the Baltic fleet to Kamchatka via the Cape of Good Hope and Sunda Strait.

Between 1791 and 1802, the wealthy merchant Thorkler from Reval (Tallinn) undertook several round-the-world and half-round-the-world expeditions on French ships, visiting places such as Petropavlovsk-Kamchatsky, Nootka Island, Canton, and Kolkata.

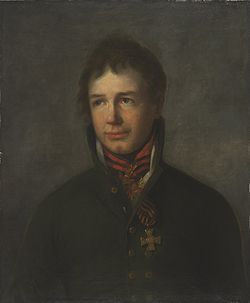

A new opportunity arose under the rule of Alexander I, as the Russian government faced financial strain due to its involvement in the Second and Third Coalitions against France, leading Krusenstern to resubmit his plan.

He argued for robust state support for large, private enterprises to develop shipping in the Pacific and proposed using ports in Northwest America and Kamchatka to strengthen the Russian position in the fur trade while reducing the strength of England and the US.

[10][18] On July 29, 1802, Minister of Commerce Nikolay Rumyantsev and Nikolai Rezanov, representing the Main Board of the Russian-American Company, submitted a similar project, referring to Krusenstern's original 1799 proposal.

[22] The expedition aimed to explore the Amur River and nearby areas, find convenient ports for the Russian Pacific fleet, bring cargo to Alaska, and establish trading relations with Japan and Canton.

Historians suggest that Rezanov's appointment to the expedition may have been politically motivated as a form of exile, as he allegedly conspired against Platon Zubov and Peter Ludwig von der Pahlen.

[23] Minister of Foreign Affairs, Chancellor Alexander Vorontsov, ordered Russian embassies in England, Spain, the Netherlands, Portugal, and France to ask their local governments to help the expedition.

The ambassador's retinue also included some random selections: in particular, Count Fyodor Tolstoy, hieromonk Gideon (Fedotov) from the Alexander Nevsky Lavra, and clerk Nikolai Korobitsyn from the RAC.

When playing music in the mess, Romberg was the first violin in the ship's orchestra,[note 4] while Ratmanov read books on travel and philosophy even during shifts and got annoyed if others distracted him.

Based on the recommendation of Austrian astronomer Franz Xaver von Zach, the directors hired Swiss flautist Johann Caspar Horner, who had once stolen the skull of an executed man in Macau, to serve as a specimen.

Of all officers on the Nadezhda, only Ratmanov, Rezanov, Count Tolstoy, Fyodor Shemelin (merchant), Brinkin (botanist), Kurlyandov (painter), and Petr Golovachev [ru] were of Russian origin.

Sevastyanov provided 14 basic procedures for conducting observations including marking specimens according to binomial nomenclature, sketching appearances, and conveying samples for transfer to the Imperial Cabinet of the Russian Empire.

Krusenstern thought that Antoine François Prévost's publication "Mémoires et aventures d 'un homme de qualité qui s'est retiré du monde" was so important that later he even passed it to Kotzebue: the book travelled around the world twice.

[93] On the Nadezhda, quartermaster Ivan Kurganov, who "had excellent abilities and gift of speech" dressed up as Neptune[clarification needed][94] and gave vodka to the crew that got "pretty drunk" afterwards.

Following the example of Laperouse, Krusenstern entered Brazil through the port Florianópolis, which, compared to Rio de Janeiro, had a softer climate, freshwater, and cheaper food and tariffs.

Langsdorf, who knew Portuguese, was highly interested in everything: maté consumption, the damage that cassava might cause to teeth, how local indigenous people hunted, and learning to spin cotton.

When the Nadezhda arrived at the port, Anna-Maria, Krusenstern prohibited the exchange of the RAC's axes for local rarities (pieces of jewellery or weapons) in the hope of saving them for buying more pigs later.

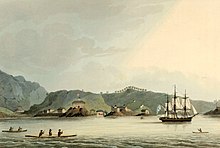

Rezanov took an "honour guard" on vacated seats: captain of the battalion of Petropavlovsk Ivan Fedorov, lieutenant Dmitry Koshelev – brother of the governor, and eight non-commissioned and privates.

[164] Rezanov had an "open list" from the Batavian Republic and the precept in the name of the head of the Dutch East India Company Hendrick Doof for assisting in maintaining the embassy's mission.

The only thing that caused genuine interest from the Japanese side was the clock (English work) from the Hermitage in the shape of an elephant, which was able to turn the trunk and ears, and the kaleidoscopic lights made by Russian inventor Ivan Kulibin.

Nevertheless, Levenstern claimed that due to the fact that Japanese did not know that it is possible to make triangulation and cartography from the board, for that short period, officers on the Nadezhda were able to conduct more material than Dutch for 300 years.

Despite the heavy rain, only Rezanov was invited to the tent where the representatives told him that they completely reject any type of trade relations[note 8] On April 7, there was a farewell ceremony where Russian members of the crew expressed a desire to leave Japan as soon as possible.

[185] Despite extreme discontent of the Japanese authorities, Krusenstern decided to return the embassy in Petropavlovsk through the Sea of Japan – along the west coast of Honshu and Hokkaido which was quite unknown to Europeans.

[202] On August 30 at 3 pm, everyone safely returned to Petropavlovsk: All this time there were rare days in which rain would not wet us, or foggy moisture penetrate our dresses; moreover, we had no fresh provisions, turning off the fish of the Gulf of Hope, and no anti-zingotic agents; but, in spite of all that, we had not a single patient on the ship.

Negotiations with the head of the indigenous population of Sitka – Sitcan toyon Kotlean – failed because Baranov demanded to surrender the fortress and pass on reliable Amanats [ru] to Russians.

By that time, the trade season had already opened, and British personnel went to Guangzhou, while the personal house of the director and the premises of the company were provided to Krusenstern and officers who wanted to scatter ashore.

[247] Despite all the difficulties, the decisiveness of the British and Russian side took effect: the goppo personally visited Nadezhda and met with Lisyansky (Krusenstern was absent) – a rare case in relations between Chinese officials and foreign merchants.

They identified the Equatorial Counter Current in the Atlantic and the Pacific Oceans, measured temperature differences at depths of up to 400 meters, and determined its specific gravity, clarity, and color.