Shoaling and schooling

An unstructured aggregation might be a group of mixed species and sizes that have gathered randomly near some local resource, such as food or nesting sites.

Many hypotheses to explain the function of schooling have been suggested, such as better orientation, synchronized hunting, predator confusion and reduced risk of being found.

The herrings keep a certain distance from a moving scuba diver or a cruising predator like a killer whale, forming a vacuole which looks like a doughnut from a spotter plane.

"Shoaling behaviour is generally described as a trade-off between the anti-predator benefits of living in groups and the costs of increased foraging competition.

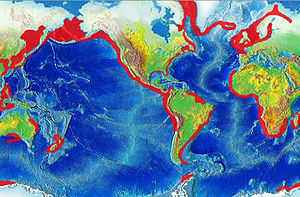

Wind-driven surface currents interact with these gyres and the underwater topography, such as seamounts, fishing banks, and the edge of continental shelves, to produce downwellings and upwellings.

Regions of notable upwelling include coastal Peru, Chile, Arabian Sea, western South Africa, eastern New Zealand and the California coast.

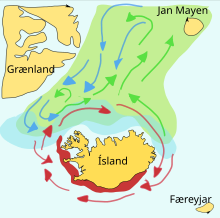

The capelin move inshore in large schools to spawn and migrate in spring and summer to feed in plankton rich areas between Iceland, Greenland, and Jan Mayen.

[12] While early laboratory-based experiments failed to detect hydrodynamic benefits created by the neighbours of a fish in a school,[19] it is thought that efficiency gains do occur in the wild.

Since fields of many fish will overlap, schooling should obscure this gradient, perhaps mimicking pressure waves of a larger animal, and more likely confuse the lateral line perception.

[43] In the detection component of the theory, it was suggested that potential prey might benefit by living together since a predator is less likely to chance upon a single group than a scattered distribution.

Adult sardines, about two years old, mass on the Agulhas Bank where they spawn during spring and summer, releasing tens of thousands of eggs into the water.

Huge numbers of sharks, dolphins, tuna, sailfish, Cape fur seals and even killer whales congregate and follow the shoals, creating a feeding frenzy along the coastline.

[46] The development of schooling behavior was probably associated with an increased quality of perception, predatory lifestyle and size sorting mechanisms to avoid cannibalism.

On the other hand, increased quality of perception would give small individuals a chance to escape or to never join a shoal with larger fish.

Threshers swim in circles to drive schooling prey into a compact mass, before striking them sharply with the upper lobe of its tail to stun them.

In South Carolina, the Atlantic bottlenose dolphin takes this one step further with what has become known as strand feeding, where the fish are driven onto mud banks and retrieved from there.

Some of these seabirds plummet from heights of 30 metres (100 feet), plunging through the water leaving vapour-like trails, similar to that of fighter planes.

To school the way they do, fish require sensory systems which can respond with great speed to small changes in their position relative to their neighbour.

[59] Parameters defining a fish shoal include: Boids simulation – needs Java The observational approach is complemented by the mathematical modelling of schools.

The most common mathematical models of schools instruct the individual animals to follow three rules: An example of such a simulation is the boids program created by Craig Reynolds in 1986.

[76] In 2009, building on recent advances in acoustic imaging,[59][77] a group of MIT researchers observed for "the first time the formation and subsequent migration of a huge shoal of fish.

"[78] The results provide the first field confirmation of general theories about how large groups behave, from locust swarms to bird flocks.

A chain reaction triggers when the population density reaches a critical value, like an audience wave travelling around a sport stadium.

[82] Consensus decision-making, a form of collective intelligence, thus effectively uses information from multiple sources to generally reach the correct conclusion.

Observations on the foraging behaviour of captive golden shiner (a kind of minnow) found they formed shoals which were led by a small number of experienced individuals who knew when and where food was available.

[85] Observations on the common roach have shown that food-deprived individuals tend to be at the front of a shoal, where they obtain more food[86][87] but where they may also be more vulnerable to ambush predators.

This has been demonstrated in guppies,[103][104] threespine stickleback,[105] banded killifish,[106] the surfperch Embiotoca jacksoni,[107] Mexican tetra,[108] and various minnows.

[109][110] A study with the White Cloud Mountain minnow has also found that choosing fish prefer to shoal with individuals that have consumed the same diet as themselves.

They can capture huge schools by rapidly encircling them with purse seine nets with the help of fast auxiliary boats and sophisticated sonar, which can track the shape of the shoal.

The squid feed primarily on small fish, crustaceans, cephalopods, and copepod, and hunt for their prey in a cooperative fashion, the first observation of such behaviour in invertebrates.