Fishery

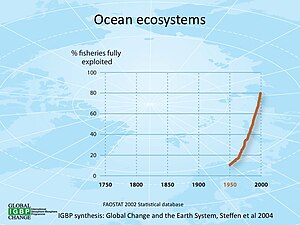

171 million tonnes of fish were produced in 2016, but overfishing is an increasing problem, causing declines in some populations.

There are commercial fisheries worldwide for finfish, mollusks, crustaceans and echinoderms, and by extension, aquatic plants such as kelp.

Some of these species are herring, cod, anchovy, tuna, flounder, mullet, squid, shrimp, salmon, crab, lobster, oyster and scallops.

[18] FAO predicted in 2018 the following major trends for the period up to 2030:[18] The goal of fisheries management is to produce sustainable biological, environmental and socioeconomic benefits from renewable aquatic resources.

Wild fisheries are classified as renewable when the organisms of interest (e.g., fish, shellfish, amphibians, reptiles and marine mammals) produce an annual biological surplus that with judicious management can be harvested without reducing future productivity.

[20][21] According to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), there are "no clear and generally accepted definitions of fisheries management".

[22] However, the working definition used by the FAO and much cited elsewhere is: The integrated process of information gathering, analysis, planning, consultation, decision-making, allocation of resources and formulation and implementation, with necessary law enforcement to ensure environmental compliance, of regulations or rules which govern fisheries activities in order to ensure the continued productivity of the resources and the accomplishment of other fisheries objectives.

[22]International attention to these issues has been captured in Sustainable Development Goal 14 "Life Below Water" which sets goals for international policy focused on preserving coastal ecosystems and supporting more sustainable economic practices for coastal communities, including in their fishery and aquaculture practices.

The study of fisheries law is important in order to craft policy guidelines that maximize sustainability and legal enforcement.

[24] This specific legal area is rarely taught at law schools around the world, which leaves a vacuum of advocacy and research.

These regulations can contain a large diversity of fisheries management schemes including quota or catch share systems.

It is important to study seafood safety regulations around the world in order to craft policy guidelines from countries who have implemented effective schemes.

Also, this body of research can identify areas of improvement for countries who have not yet been able to master efficient and effective seafood safety regulations.

According to a 2019 FAO report, global production of fish, crustaceans, molluscs and other aquatic animals has continued to grow and reached 172.6 million tonnes in 2017, with an increase of 4.1 percent compared with 2016.

The latter is largely caused by plastic-made fishing gear like drift nets and longlining equipment that are wearing down by use, lost or thrown away.

[31][32] The journal Science published a four-year study in November 2006, which predicted that, at prevailing trends, the world would run out of wild-caught seafood in 2048.

The scientists stated that the decline was a result of overfishing, pollution and other environmental factors that were reducing the population of fisheries at the same time as their ecosystems were being annihilated.