Fishing industry in Scotland

A recent inquiry by the Royal Society of Edinburgh found fishing to be of much greater social, economic and cultural importance to Scotland than it is relative to the rest of the UK.

[1] Many of these are ports in relatively remote communities such as Kinlochbervie and Lerwick, which are scattered along an extensive coastline and which, for centuries, have looked to fishing as the main source of employment.

This, coupled with the coming of the railways as a means of more rapid transport, gave an opportunity to Scottish fishermen to deliver their catches to markets much more quickly than in the past.

[1] At the peak of the Herring Boom in 1907, 2,500,000 barrels of fish (227,000 tonnes) were cured and exported, the main markets being Germany, Eastern Europe and Russia.

Technical developments have concentrated fishing in the hands of fewer fishermen operating more efficient vessels and, although the annual value of catches continued to rise, the number of people working in the industry fell.

The concept of "freedom of the seas" has endured since the seventeenth century, when the Dutch merchant and politician, Hugo Grotius, defended the Dutch Republic's trading in the Indian Ocean, with the argument of "mare librum", based on the idea that fish stocks were so abundant that there could be no possible benefit obtained by claiming national jurisdiction over large areas of sea.

[4] Countries such as Scotland had claimed exclusive rights to fishing in inshore waters as early as the fifteenth century, but there was no formal consensus as to how far off shore these areas extended.

An agreement on the two regulations which make up the CFP was eventually reached on the night of 30 June 1970 - the day that negotiations were due to start for the accession of the UK, Ireland, Denmark and Norway.

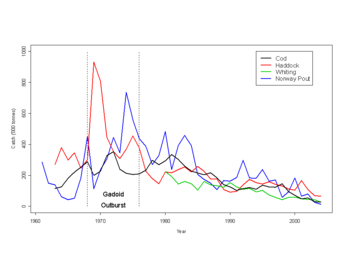

[1] The late 1960s and early 1970s were characterised by a sudden and unexplained increase in the abundance of a number of gadoid species (cod, haddock, whiting, etc.

Compromise was reached when it was agreed that the applicant countries would retain their 6-mile (11 km) exclusive limits, and their 12-mile (19 km) limits subject to existing historical rights, for substantial parts of their coastline, preventing continental European vessels fishing in much of the Scottish west coast, including all of the Minch and Irish Sea.

These limits have been renewed in legislation on two occasions, and although these rights are not a permanent feature of the policy, it is unlikely now that they will ever be extinguished, especially in the light of the need to conserve fish stocks.

[1] In January 1977, at the behest of the EEC, the UK and other member states extended their Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs) to 200 miles (370.4 km) or to the median line with other countries.

[6] The current status of the fishing industry in Scotland is best considered on a sector-by-sector basis, as each faces different problems and opportunities.

The Scottish demersal fleet has been facing economically difficult times for several years due to the decline of cod and haddock in the North Sea, which were the mainstay of catches.

This sector catches a diverse range of species and, although cod and haddock are important components, together accounting for 40% of the total landings, in absolute value they represent only a modest turnover of £55m.

This difference in behaviour, coupled with the inherent problem in measuring the age of crustaceans, means that standard stock assessment techniques cannot be used.

[9][10] The commercial performance of this sector suffered a near terminal setback during the 1970s, when the herring fisheries in the North Sea and west of Scotland collapsed and had to be closed.

These trends encouraged a number of enterprising fishermen to set about investing in the modernisation of the fleet through the commissioning of new, state-of-the-art vessels.

2006 raids by the Scottish Fisheries Protection Agency (SFPA) on a number of fish processors revealed large-scale misreporting of landings by pelagic vessels.

[1] Geographical distribution of the turnover of the Scottish industry is 77 % around Aberdeen; 24% in central and southern Scotland; and 11 per cent in the Highlands and Islands.

It accounts for more jobs than the catching industry and aquaculture combined, with the added significance that it provides employment for women in otherwise male-dominated labour markets.

Two distinct sub-sectors make up the processing industry: the primary processors involved in the filleting and freezing of fresh fish for onward distribution to fresh fish retail and catering outlets, and the secondary processors producing chilled, frozen and canned products for the retail and catering trades.

Difficulties in attracting local labour reflect the low pay, the seasonal or casual nature of employment and the poor work environment compared with office or supermarket jobs.

As a result, firms are now turning increasingly to agency labour and the employment of unskilled (and occasionally illegal[12]) immigrant workers.