Flatiron Building

The building's steel frame, designed by structural engineering firm Purdy and Henderson, was intended to withstand four times the maximum wind force of the area.

[34] This left four stories of the Cumberland's northern face exposed, which Eno rented out to advertisers, including The New York Times, which installed a sign made up of electric lights.

[37][38] Eno later put a canvas screen on the wall, projecting images from a magic lantern atop one of his smaller buildings, where he alternately presented advertisements and interesting pictures.

Both the Times and the New-York Tribune began using the screen for news bulletins, and on election nights tens of thousands of people would gather in Madison Square, waiting for the latest results.

The New York State Assembly appropriated $3 million for the city to buy it, but this fell through when a newspaper reporter discovered that the plan was a graft scheme by Tammany Hall boss Richard Croker.

Around the same time, the New York City Department of Buildings (DOB) indicated that it would refuse to approve Purdy's initial plans unless the engineers submitted detailed information about the framework, fireproofing, and wind-bracing systems.

[78] Purdy complied with most of the DOB's requests, submitting detailed drawings and documents, but he balked at the department's requirement that the design include fire escapes.

[121][122] Other tenants included an overflow of music publishers from "Tin Pan Alley" on 28th Street;[118] a landscape architect;[119] the Imperial Russian Consulate, which took up three floors;[36] the New York State Athletic Commission;[123] the Bohemian Guides Society;[119] the Roebling Construction Company, owned by the sons of Tammany Hall boss Richard Croker; and the crime syndicate Murder, Inc.[121] The puppeteer Tony Sarg had a studio in the Flatiron Building during the 1910s.

[127] Ultimately, part of the basement was occupied by the Flatiron Restaurant, which could seat 1,500 patrons and was open from breakfast through late supper for those taking in a performance at one of the many theatres which lined Broadway between 14th and 23rd Streets.

After U.S. Realty constructed the New York Hippodrome, Madison Square Garden was no longer the venue of choice, and survived largely by staging boxing matches.

As an innovation to attract customers from another restaurant opened by his brothers, Bustanoby hired a black musical group, Louis Mitchell and his Southern Symphony Quintette, to play dance tunes at the Taverne and the Café.

[155] The new owners made some superficial changes in the early 1950s, such as adding a dropped ceiling to the lobby and replacing the original mahogany-paneled entrances with revolving doors.

[162][163] According to McCormack, the company's authors were "fascinated" by the building; he said it was "the only office I know of where you can stand in one place and see the East River, the Hudson and Central Park without moving".

These "point" offices are the most coveted and feature amazing northern views that look directly upon another famous Manhattan landmark, the Empire State Building.

[191] Mainetti subsequently said in 2015 that, when Macmillan's lease expired, "There possibly is going to be an upgrade and the building could make also a good potential hotel conversion, which we're not completely taking off the table.

[160] GFP Real Estate announced that it would upgrade the building's interior, since the structure would be almost completely vacant,[160][197] except for a T-Mobile store at the base.

[208] According to Jeffrey Gural, who came in second in the bidding, immediately after the auction on the steps of the New York County Courthouse, Garlick asked him if he wanted to partner in the building, later offering a 10% stake in return for putting up the $19 million down payment.

[110] Burnham initially did not want to add the "cowcatcher" space, since he believed it would ruin the symmetry of the prow's design, but he was forced to accept the addition on Black's insistence.

The windows are flanked by alternating wide and narrow piers, each of which contains terracotta panels with decorations such as foliate motifs, masks, lozenges, and wreaths.

[251] The construction of the Flatiron was made feasible by a change to New York City's building codes in 1892, which eliminated the requirement that masonry be used for fireproofing considerations.

[258] At ground level, the building's northern prow is cantilevered from a pair of elliptical girders, while the southwest and southeast corners contain diagonal floor beams.

[104][91] According to The New York Times, offices in the prow had "impressive" views "because of the converging traffic street markings, which accent the telescoping boulevards, and because of the changing seasons in Madison Square Park".

[113][279] The New-York Tribune called the new building "A stingy piece of pie ... the greatest inanimate troublemaker in New York",[11] a sentiment repeated by Architectural Record.

Futurist H. G. Wells wrote in his 1906 book The Future in America: A Search After Realities: "I found myself agape, admiring a sky-scraper the prow of the Flat-iron Building, to be particular, ploughing up through the traffic of Broadway and Fifth Avenue in the afternoon light.

[229] Karl Zimmermann of The Washington Post wrote in 1987 that the Flatiron was "an idiosyncratic wedge blanketed with French Renaissance ornamentation, still remarkable today in its lightness, grace and novelty.

[283] Stieglitz reflected on the dynamic symbolism of the building, noting upon seeing it one day during a snowstorm that "... it appeared to be moving toward me like the bow of a monster ocean steamer – a picture of a new America still in the making.

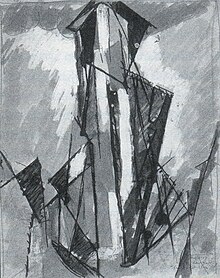

Painters of the Ashcan School, like John Sloan, Everett Shinn, and Ernest Lawson also painted images of the building, as did Paul Cornoyer and Childe Hassam.

"[291] Due to the geography of the site, with Broadway on one side, Fifth Avenue on the other, and the open expanse of Madison Square and the park in front of it, the wind currents around the building could be treacherous.

[296] The winds prompted a lawsuit from a nearby property owner,[297] and they were also blamed for the 1903 death of a bicycle messenger, who was blown into the street and run over by a car.

[300] This was in part because many buildings occupied rectangular sites on Manhattan's street grid;[301] furthermore, developers tended to avoid buying oddly-shaped plots, as their unconventional dimensions were hard to market to potential tenants.