Flavian dynasty

The Flavian dynasty, lasting from 69 to 96 CE, was the second dynastic line of emperors to rule the Roman Empire following the Julio-Claudians, encompassing the reigns of Vespasian and his two sons, Titus and Domitian.

The reign of Titus was struck by multiple natural disasters, the most severe of which was the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 CE, which saw the surrounding cities of Pompeii and Herculaneum be completely buried under ash and lava.

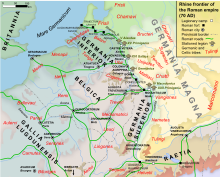

Substantial conquests were made in Great Britain under the command of Gnaeus Julius Agricola between 77 and 83 CE, while Domitian was unable to procure a decisive victory against King Decebalus in the war against the Dacians.

Following a prolonged period of retirement during the 50s, he returned to public office under Nero, serving as proconsul of the Africa province in 63, and accompanying the emperor during an official tour of Greece in 66.

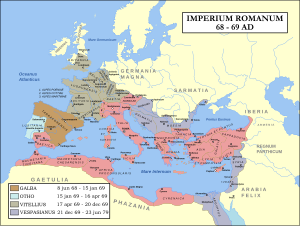

[24] A strong force drawn from the Judaean and Syrian legions marched on Rome under the command of Mucianus, while Vespasian himself traveled to Alexandria, leaving Titus in charge of ending the Jewish rebellion.

Terms of peace, including a voluntary abdication, were agreed upon with Titus Flavius Sabinus II,[28] but the soldiers of the Praetorian Guard—the imperial bodyguard—considered such a resignation disgraceful, and prevented Vitellius from carrying out the treaty.

With nothing more to be feared from the enemy, Domitian came forward to meet the invading forces; he was universally saluted by the title of Caesar, and the mass of troops conducted him to his father's house.

[30] Upon receiving the tidings of his rival's defeat and death at Alexandria, the new Emperor at once forwarded supplies of urgently needed grain to Rome, along with an edict or a declaration of policy, in which he gave assurance of an entire reversal of the laws of Nero, especially those relating to treason.

[37] Despite initial concerns over his character, Titus ruled to great acclaim following the death of Vespasian on 23 June 79, and was considered a good emperor by Suetonius and other contemporary historians.

[43] Domitian was declared emperor by the Praetorian Guard the day after Titus' death, commencing a reign which lasted more than fifteen years—longer than any man who had governed Rome since Tiberius.

Domitian strengthened the economy by revaluing the Roman coinage,[44] expanded the border defenses of the Empire,[45] and initiated a massive building programme to restore the damaged city of Rome.

[46] In Britain, Gnaeus Julius Agricola expanded the Roman Empire as far as modern day Scotland,[47] but in Dacia, Domitian was unable to procure a decisive victory in the war against the Dacians.

Modern history has rejected these views, instead characterising Domitian as a ruthless but efficient autocrat, whose cultural, economic and political programme provided the foundation for the Principate of the peaceful 2nd century.

He became personally involved in all branches of the administration: edicts were issued governing the smallest details of everyday life and law, while taxation and public morals were rigidly enforced.

Whereas his father and brother had virtually excluded non-Flavians from public office, Domitian rarely favoured his own family members in the distribution of strategic posts, admitting a surprisingly large number of provincials and potential opponents to the consulship,[58] and assigning men of the equestrian order to run the imperial bureaucracy.

[61] Coin types from this era display a highly consistent degree of quality, including meticulous attention to Domitian's titulature, and exceptionally refined artwork on the reverse portraits.

Josephus describes a procession with large amounts of gold and silver carried along the route, followed by elaborate re-enactments of the war, Jewish prisoners, and finally the treasures taken from the Temple of Jerusalem, including the Menorah and the Torah.

[72] Although the Romans inflicted heavy losses on the Caledonians, two-thirds of their army managed to escape and hide in the Scottish marshes and Highlands, ultimately preventing Agricola from bringing the entire British island under his control.

[73] His most significant military contribution was the development of the Limes Germanicus, which encompassed a vast network of roads, forts and watchtowers constructed along the Rhine river to defend the Empire.

[76] In 87, the Romans invaded Dacia once more, this time under command of Tettius Julianus, and finally managed to defeat Decebalus late in 88, at the same site where Fuscus had previously been killed.

[77] An attack on Dacia's capital was abandoned, however, when a crisis arose on the German frontier, forcing Domitian to sign a peace treaty with Decebalus which was severely criticized by contemporary authors.

[78] For the remainder of Domitian's reign Dacia remained a relatively peaceful client kingdom, but Decebalus used the Roman money to fortify his defenses, and continued to defy Rome.

On 24 August 79, barely two months after his accession, Mount Vesuvius erupted,[80] resulting in the almost complete destruction of life and property in the cities and resort communities around the Bay of Naples.

[82] Titus appointed two ex-consuls to organise and coordinate the relief effort, while personally donating large amounts of money from the imperial treasury to aid the victims of the volcano.

[83][84] Although the extent of the damage was not as disastrous as during the Great Fire of 64, crucially sparing the many districts of insulae, Cassius Dio records a long list of important public buildings that were destroyed, including Agrippa's Pantheon, the Temple of Jupiter, the Diribitorium, parts of Pompey's Theatre and the Saepta Julia among others.

[85] According to the historian John Crook, however, the alleged conspiracy was in fact a calculated plot by the Flavian faction to remove members of the opposition tied to Mucianus, with the mutinous address found on Caecina's body a forgery by Titus.

"I will not kill a dog that barks at me," were words expressing the temper of Vespasian, while Titus once demonstrated his generosity as Emperor by inviting men who were suspected of aspiring to the throne to dinner, rewarding them with gifts and allowing them to be seated next to him at the games.

The senatorial officers may have disapproved of Domitian's military strategies, such as his decision to fortify the German frontier rather than attack, his recent retreat from Britain, and finally the disgraceful policy of appeasement towards Decebalus.

[108] In addition to providing spectacular entertainments to the Roman populace, the building was conceived as a gigantic triumphal monument to commemorate the military achievements of the Flavians during the Jewish wars.

All the surviving accounts from this period, many of them written by his own contemporaries such as Suetonius Tranquillus, Cassius Dio, and Pliny the Elder, present a highly favourable view towards Titus.