Flora of Madagascar

The high degree of endemism is due to Madagascar's long isolation following its separation from the African and Indian landmasses in the Mesozoic, 150–160 and 84–91 million years ago, respectively.

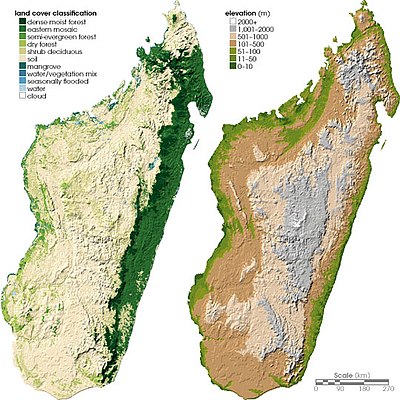

Dry forest and succulent woodland are found in the drier western part and grade into the unique spiny thicket in the southwest, where rainfall is lowest and the wet season shortest.

Among them are rice, the staple dish of Malagasy cuisine grown in terraced fields in the highlands, and greater yam, taro, cowpea, and plantain.

Madagascar's high endemism and species richness coupled with a sharp decrease in primary vegetation make the island a global biodiversity hotspot.

To preserve natural habitats, around 10% of the land surface is protected, including the World Heritage sites Tsingy de Bemaraha and the Rainforests of the Atsinanana.

While historically mainly European naturalists described Madagascar's flora scientifically, today a number of national and international herbaria, botanical gardens and universities document plant diversity and engage in its conservation.

Palm genera that are endemic to Madagascar are Beccariophoenix, Bismarckia, Dypsis, Lemurophoenix, Marojejya, Masoala, Ravenea, Satranala, Tahina, and Voanioala.

The endemic traveller's tree (Ravenala madagascariensis), a national emblem and widely planted, is the sole Madagascan species in the family Strelitziaceae.

[8] The chytrid fungus Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis, responsible for chytridiomycosis, an infectious disease threatening amphibian populations worldwide, was long considered absent from Madagascar.

The geology of Madagascar features mainly igneous and metamorphic basement rocks, with some lava and quartzite in the central and eastern plateaus, while the western part has belts of sandstone, limestone (including the tsingy formations), and unconsolidated sand.

The predominantly evergreen forest, up to 35 m high (115 ft), is composed of tree and understory species from various families such as Burseraceae, Ebenaceae, Fabaceae, and Myristicaceae; bamboos and lianas are frequent.

[17] At higher altitudes on thin soil, they grade into an indigenous, hard-leaved vegetation that includes Asteraceae, Ericaceae, Lauraceae, and Podocarpaceae shrubs, among others,[13] and is singled out by the WWF as "ericoid thickets" ecoregion.

[25] Molecular clock analyses however suggest that most plant and other organismal lineages immigrated via across-ocean dispersal, given that they are estimated to have diverged from continental groups well after Gondwana broke up.

[27] Most extant plant groups have African affinities, consistent with the relatively small distance to the continent, and there are also strong similarities with the Indian Ocean islands of the Comoros, Mascarenes, and Seychelles.

Humid forests probably established since the Oligocene, when India had cleared the eastern seaway, allowing trade winds to bring in rainfall, and Madagascar had moved north of the subtropical ridge.

The intensification of the Indian Ocean monsoon system after around eight million years ago is believed to have further favoured the expansion of humid and sub-humid forests in the Late Miocene, especially in the northern Sambirano region.

[28] A Madagascan lineage of Euphorbia occurs across the island, but some species evolved succulent leaves, stems and tubers in adaptation to arid conditions.

[30] Madagascar's fauna is thought to have coevolved to a certain extent with its flora: The famous plant–pollinator mutualism predicted by Charles Darwin, between the orchid Angraecum sesquipedale and the moth Xanthopan morganii, is found on the island.

[33] The extinct Madagascan megafauna also included grazers such as two giant tortoises (Aldabrachelys) and the Malagasy hippopotamuses, but it is unclear to what extent their habitats resembled today's widespread grasslands.

Its only overseas connections were occasional Arab, Portuguese, Dutch, and English sailors, who brought home anecdotes and tales about the fabulous nature of Madagascar.

[37][38] About one century later, in 1770, French naturalists and voyagers Philibert Commerson and Pierre Sonnerat visited the island from the Isle de France (now Mauritius).

[39] They collected and described a number of plant species, and many of Commerson's specimens were described later by Jean-Baptiste de Lamarck and Jean Louis Marie Poiret in France.

[36]: 185–187 The British missionary and naturalist Richard Baron, Grandidier's contemporary, lived in Madagascar from 1872 to 1907 where he also collected plants and discovered up to 1,000 new species;[44] many of his specimens were described by Kew botanist John Gilbert Baker.

It holds a herbarium with roughly 700,000 Malagasy plant specimens and a seed bank and living collection, and continues to edit the Flore de Madagascar et des Comores series begun by Humbert in 1936.

Later European traders and colonists introduced crops like litchi and avocado[66] and promoted the cultivation of exports like cloves, coconut, coffee and vanilla in plantations.

[66] The traditional slash-and-burn agriculture (tavy), practised for centuries, today accelerates the loss of primary forests as populations grow[69] (see below, Threats and conservation).

[66] A notorious example is the South American water hyacinth (Eichhornia crassipes), which spread widely through subtropical and tropical regions and is considered a serious plant pest in wetlands.

[71] A prickly pear cactus, Opuntia monacantha, was introduced to southwest Madagascar in the late 18th century by French colonialists, who used it as natural fence to protect military forts and gardens.

[71] Madagascar, together with its neighbouring islands, is considered a biodiversity hotspot because of its high species richness and endemism coupled with a dramatic decrease of primary vegetation.

[79] Global warming is expected to reduce or shift climatically suitable areas for plant species and threatens coastal habitats, such as littoral forests, through rising sea levels.