Floyd Bennett Field

[10] Floyd Bennett Field was New York City's first municipal airport, built largely in response to the growth of commercial aviation after World War I.

[14] In mid-1927, Herbert Hoover, the United States Secretary of Commerce, approved the creation of a "Fact-Finding Committee on Suitable Airport Facilities for the New York Metropolitan District".

[25] La Guardia, along with Representative William W. Cohen, introduced a motion in the 70th United States Congress to establish the airport on Governors Island, but it was voted down.

[18] However, airline companies feared that the Barren Island Airport would have low visibility during foggy days,[22] a claim Chamberlin disputed because he said there was little history of fog in the area.

One of the members of Hoover's Fact-Finding Committee objected because Middle Village was located at a higher elevation with less fog, while Barren Island was more frequently foggy during the spring and fall.

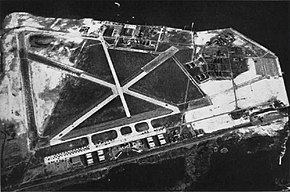

[67] As a general aviation airfield, Floyd Bennett Field attracted the record-breaking pilots of the interwar period because of its superior modern facilities, lack of nearby obstacles, and convenient location near the Atlantic Ocean (see § Notable flights).

[69] Various improvements were made to the airport throughout its entire commercial existence: first as a seaplane hangar, then by the Works Progress Administration (WPA), and finally by the United States Navy.

[87] In December 1935, a meeting was held at the Post Office Department headquarters in Washington, D.C., concerning Floyd Bennett Field's suitability as an airmail terminal.

[88] Grover Whalen, chairman of La Guardia's Committee on Airport Development, argued that the city had an "inalienable right" to appear on maps of the United States' airspace, and that Floyd Bennett Field was ready for use as an alternate airmail terminal.

[89] In March 1936, Farley announced that he had rejected the bid to move airmail operations to Floyd Bennett Field because all evidence showed that doing so would cause a decline in traffic and profits.

[65] Spurred by the expansion of air travel across the United States, the Department of Docks began planning extensive upgrades to Floyd Bennett Field in 1934.

[70] In 1939, the Navy started constructing a base for 24 seaplanes at Floyd Bennett Field, in preparation for expanding its "neutrality patrol" activities during World War II.

[129] In addition, Navy WAVES (Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service) took up several positions, including those of air traffic controllers, parachute riggers, and aviation machinist's mates.

[149][152] At the time, it was the largest Naval Air Reserve base in the U.S.[154] The Navy demolished many of the temporary structures, including the barracks, as well as the outdated Sperry floodlights.

The Navy lengthened three runways, reconstructed roads and taxiways, built a beacon tower and veterans' housing, and added some fuel storage containers.

[168][169] During the height of the Vietnam War in the late 1960s, military budgets were strained by a combination of combat operations in Southeast Asia and funding constraints due to President Lyndon Johnson's concurrent Great Society programs.

[172][160] On April 4, 1970, the Navy conducted its last daily formal inspections, an act that started the process of decommissioning NAS New York / Floyd Bennett Field.

The field's chief park ranger at the time attributed the low visitor count to several factors, including "the chain-link fence along Flatbush Avenue, the Coast Guard station and the guardhouse".

[195]: 33 A small portion remained in the possession of the Coast Guard's parent agency at the time, U.S. Department of Transportation, so the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) could use it.

[189] The New York City Department of Sanitation (DSNY) also moved into Floyd Bennett Field by the late 1990s, using the runways as a location for truck-driving practice.

[208] In the immediate aftermath of Hurricane Sandy in October and November 2012, a portion of one runway was used as a staging area by the Federal Emergency Management Agency, for relief workers who were conducting rescues and evacuations in the Rockaways.

Senators Chuck Schumer and Kirsten Gillibrand announced that a bill with a $2.4 million upgrade for the New York State Marine Corps Reserve complex in Brooklyn had passed in the U.S.

[212] Nonprofit organization Jamaica Bay-Rockaway Parks Conservancy presented plans to the Brooklyn Community Board 18 in April 2023 for the restoration of three structures at Floyd Bennett Field.

[226][228][56] The neoclassical details of the building, which can also be found in train stations and post offices built in the early 20th century, were purposely included to give passengers a familiar feeling.

[226] Before the tunnels were added during the WPA renovations, passengers exiting out the eastern side of the building would descend to the airport apron, where they could board planes from ground level.

The $600,000 steel-framed Hangar A, which was built to house the Navy's flying boats, contains a steel frame and glazed sliding doors to the north and south.

[257][230] The 2-acre (0.81 ha) freshwater Return-A-Gift pond, built circa 1980, is also located in the North Forty Area, near the clear flight path zone for Runway 12–30.

[63][263][264] On July 28–30, 1931, Russell Norton Boardman and John Louis Polando flew a Bellanca Special J-300 high-wing monoplane named Cape Cod to Istanbul’s Yeşilköy Airport—now Atatürk Airport—in 49:20 hours, establishing a straight-line distance record of 5,011.8 miles (8,065.7 km).

[267][268] Seventeen minutes after Boardman and Polando departed, Hugh Herndon Jr. and Clyde Pangborn flew a Red Bellanca CH-400 Skyrocket, named Miss Veedol, to Moylgrove, Wales, in 31:42 hours.

Corrigan used a second-hand surplus aircraft, a Curtiss Robin powered by a 165 hp (123 kW) Wright Whirlwind J-6 engine, and his flight was registered to go to California.