Concepts in folk art

Tangible and intangible folk arts were developed to address a need, and are shaped by generational values derived from family and community, through demonstration, conversation and practice.

This social identity eventually broadened to represent the underclass of modern society due to the rise in popularity of Marxist theory in the academic world, which began to identify both the rural and urban poor as allied subjects of economic inequality.

During the Middle Ages in Europe, a high proportion of surviving objects, including statues, paintings, drawings, and building arts were directly tied to the messaging and stories of the Roman Catholic church and individual salvation; they were created to the glory of God.

The original meaning of the word art, then, was quite clear: it applied to any kind of skill.”[5][6] Prior to1500 AD, all material artifacts were created by hand by individual artisans, each of whom was more or less skilled in his or her craft.

In the parlance of this new age, these artisans were said to display individual personal inspiration in their work instead of an exceptional mastery of the age-old practices of their craft.

[8] These new labels connoted a qualitatively inferior object, the assumption was that they were of a lesser quality than the newly defined European fine arts.

In succinct terms, then, we can define art as the manifestation of a skill that involves the creation of a qualitative experience (often categorized as aesthetic) through the manipulation of whatever forms that are public categories recognized by a particular group.

"[13] Despite all attempts at categorization by art critics, consumers, marketeers and folklorists, the object itself remains an authentic cultural artifact that some individual somewhere created to address a (real or perceived) need.

Once this conventional aesthetic hierarchy has been eliminated[14] and the component of exclusivity is removed, there is no more and no less in these three labels; craftsman, artisan, and artist all include a high level of skill in their given media.

Removed from their original context of production and utility within the local community, these objects were valued as standalone curiosities from an earlier time in American history.

It was at the mid-point of the century, at the same time that folklore as performance began to dominate the discussions, and professionals of folkloristics and cultural history became more selective in what they wanted to label as folk art.

[20] Despite this early appreciation of their work, it took another 50 years for folk artists to acquire the recognition they merit, no longer eclipsed by the constricted spotlight on the individual object.

Facile and narrow labels that reduce the creative spirit to a single dimension are of little significance in the long run, especially when they obscure the multiplicity of intentions, ideas, meanings, influences, connections, and references inherent in every work of art.

Using simple, often handmade tools, manual techniques, and local materials, these craftsmen devoted more time to their craft than they did to any patch of land they were cultivating.

[27] Folk artisans were trained in their trade in one of several ways, including through family lines where a parent would pass knowledge and tools onto their children to continue working in the skilled craft.

These master craftsmen looked for opportunities in their new country to use these skills, train apprentices and imprint their new communities with folk objects from their European heritage.

In 1932 Allen H. Eaton, published a book "Immigrant Gifts to American Life" which showcased the arts and skills of foreigners at the Buffalo Exhibition.

The artisans in these communities continue to make the hand tools needed to maintain their rural lifestyle, and also to find or invent acceptable technical ways to bridge the gap between themselves and the modern world which surrounds them.

In this activity the artisan moves into a different mental zone, absorbed in something outside of himself, separate and distinct from the rational mindset of most of our waking hours.

The list below includes a sampling of different materials, forms, and artisans involved in the production of everyday and folk art objects.

They strive to create an object which matches community expectations, working within (mostly) unspoken cultural biases to confirm and strengthen the existing model.

If the decorated pitcher drips every time it is used to pour, if the ornate cupboard door does not close all the way, if the roof leaks, if the object does not work as intended then its value and assessment is immediately reduced.

Kubler formulated this succinctly: “Sculpture and painting convey distinct messages… These communications or iconographic themes make the utilitarian and rational substructure of any aesthetic achievement.

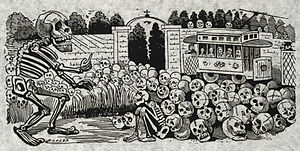

[note 6] These illustrated representations of community life have now become more decorative; the original functions have been replaced by the rise in literacy and the explosion of easily accessible printed materials.

"[59] It is this repetition that "proves the absence of mistake and presence of control," providing "the traditional repetitive-symmetrical aesthetic" of Western folk art.

[note 7] It became evident that "Not insignificantly, the politics of the marketplace have had an impact on the development of terminology…"[67] The new field of museum folklore now assumes a position of intermediary between the interested parties.

These include folk artists working in quilting, ironwork, woodcarving, pottery, embroidery, basketry, weaving, and other related traditional arts.

"[69] As the reputation of these master craftsmen grows, "individual purchasers, small shop owners and their sales reps, crafts fair and bazaar managers, large department store and mail order catalog buyers, philanthropic organizations... actively engaged in tailoring the products…" to sell.

[71] And yet for many folk artists, the price paid for their hand-crafted product does not even match the minimum wage requirement for the hours they spend on crafting each item.

"[72] With name recognition of the traditional artist, their craft and their product is removed from the community to be marketed in the western consumer economy, and becomes a commodity reflective more of the person who buys it than of the master craftsman.