Folklore studies

94-201)[7] passed in 1976 by the United States Congress in conjunction with the Bicentennial Celebration included a definition of folklore, also called folklife: "...[Folklife] means the traditional expressive culture shared within the various groups in the United States: familial, ethnic, occupational, religious, regional; expressive culture includes a wide range of creative and symbolic forms such as custom, belief, technical skill, language, literature, art, architecture, music, play, dance, drama, ritual, pageantry, handicraft; these expressions are mainly learned orally, by imitation, or in performance, and are generally maintained without benefit of formal instruction or institutional direction."

[citation needed] A contemporary definition of folk is a social group which includes two or more persons with common traits, who express their shared identity through distinctive traditions.

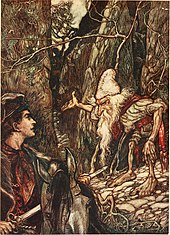

[citation needed] The "Kinder- und Hausmärchen" of the Brothers Grimm, first published 1812, is the best known collection of the verbal folklore of the European peasantry.

This interest in stories, sayings and songs, i.e. verbal lore, continued throughout the 19th century and aligned the fledgling discipline of folklore studies with literature and mythology.

Lomax and Botkin emphasized applied folklore, with modern public sector folklorists working to document, preserve and present the beliefs and customs of diverse cultural groups in their region.

[citation needed] Its synonym, folklife, came into circulation in the second half of the 20th century, at a time when some researchers felt that the term folklore was too closely tied exclusively to oral lore.

For example, vernacular architecture denotes the standard building form of a region, using the materials available and designed to address functional needs of the local economy.

The folklorist also rubs shoulders with researchers, tools and inquiries of neighboring fields: literature, anthropology, cultural history, linguistics, geography, musicology, sociology, psychology.

[23] In his published call for help in documenting antiquities, Thoms was echoing scholars from across the European continent to collect artifacts of older, mostly oral cultural traditions still flourishing among the rural populace.

[25] With increasing industrialization, urbanization, and the rise in literacy throughout Europe in the 19th century, folklorists were concerned that the oral knowledge and beliefs, the lore of the rural folk would be lost.

[30] Folklore became a measure of the progress of society, how far we had moved forward into the industrial present and indeed removed ourselves from a past marked by poverty, illiteracy and superstition.

The task of both the professional folklorist and the amateur at the turn of the 20th century was to collect and classify cultural artifacts from the pre-industrial rural areas, parallel to the drive in the life sciences to do the same for the natural world.

"[31] Viewed as fragments from a pre-literate culture, these stories and objects were collected without context to be displayed and studied in museums and anthologies, just as bones and potsherds were gathered for the life sciences.

As the number of classified artifacts grew, similarities were noted in items which had been collected from very different geographic regions, ethnic groups and epochs.

[37] Using multiple variants of a tale, this investigative method attempted to work backwards in time and location to compile the original version from what they considered the incomplete fragments still in existence.

As a proponent of this method, Walter Anderson proposed additionally a Law of Self-Correction, i.e. a feedback mechanism which would keep the variants closer to the original form.

[41] In contrast to this, American folklorists, under the influence of the German-American Franz Boas and Ruth Benedict, sought to incorporate other cultural groups living in their region into the study of folklore.

The folklore collected under the auspices of the Federal Writers Project during these years continues to offer a goldmine of primary source materials for folklorists and other cultural historians.

The vocabulary of German Volkskunde such as Volk (folk), Rasse (race), Stamm (tribe), and Erbe (heritage) were frequently referenced by the Nazi Party.

[48] Particularly in the works of Hermann Bausinger and Wolfgang Emmerich in the 1960s, it was pointed out that the vocabulary current in Volkskunde was ideally suited for the kind of ideology that the National Socialists had built up.

Oral traditions, particularly in their stability over generations and even centuries, provide significant insight into the ways in which insiders of a culture see, understand, and express their responses to the world around them.

[note 7] Once classified, it was easy for structural folklorists to lose sight of the overarching issue: what are the characteristics which keep a form constant and relevant over multiple generations?

True to each of these approaches, and any others one might want to employ (political, women's issues, material culture, urban contexts, non-verbal text, ad infinitum), whichever perspective is chosen will spotlight some features and leave other characteristics in the shadows.

Many other poets and writers throughout the Turkish nation began to join in on the movement including Ahmet Midhat Efendi who composed short stories based on the proverbs written by Sinasi.

[citation needed] Ramón Laval, Julio Vicuña, Rodolfo Lenz, José Toribio Medina, Tomás Guevara, Félix de Augusta, and Aukanaw, among others, generated an important documentary and critical corpus around oral literature, autochthonous languages, regional dialects, and peasant and indigenous customs.

[63] Along with these new challenges, electronic data collections provide the opportunity to ask different questions, and combine with other academic fields to explore new aspects of traditional culture.

[68] Noyes[69] uses similar vocabulary to define [folk] group as "the ongoing play and tension between, on the one hand, the fluid networks of relationship we constantly both produce and negotiate in everyday life and, on the other, the imagined communities we also create and enact but that serve as forces of stabilizing allegiance.

The goal of the early folklorists of the historic-geographic school was to reconstruct from fragments of folk tales the Urtext of the original mythic (pre-Christian) world view.

[75] Lacking the European mechanistic devices of marking time (clocks, watches, calendars), they depended on the cycles of nature: sunrise to sunset, winter to summer.

The folklorist Bill Ellis accessed internet humor message boards to observe in real time the creation of topical jokes following the 9/11 terrorist attack in the United States.