Humanitarian aid

Humanitarian aid generally refers to the provision of immediate, short-term relief in crisis situations, such as food, water, shelter, and medical care.

Humanitarian assistance, on the other hand, encompasses a broader range of activities, including longer-term support for recovery, rehabilitation, and capacity building.

Such aid emerged when international organizations stepped in to respond to the need of national governments for global support and partnership to address natural disasters, wars, and other crises that impact people's health.

[10] Finally, humanitarian medical aid assumes a biomedical approach which does not always account for the alternative beliefs and practices about health and well-being in the affected regions.

[21] The approach also encompasses humanitarian transportation, the goal of which is to ensure migrants and refugees retain access to basic goods and services and the labour market.

[20] Basic needs, including access to shelter, clean water, and child protection, are supplemented by the UN's efforts to facilitate social integration and legal regularization for displaced individuals.

[22] The recent rise in Big Data, high-resolution satellite imagery and new platforms powered by advanced computing have already prompted the development of crisis mapping to help humanitarian organizations make sense of the vast volume and velocity of information generated during disasters.

For example, crowdsourcing maps (such as OpenStreetMap) and social media messages in Twitter were used during the 2010 Haiti Earthquake and Hurricane Sandy to trace leads of missing people, infrastructure damages and raise new alerts for emergencies.

Women have limited access to paid work, are at risk of child marriage, and are more exposed to Gender based violence, such as rape and domestic abuse.

Similarly, FFW programs in Cambodia have shown to be an additional, not alternative, source of employment and that the very poor rarely participate due to labor constraints.

Nevertheless, research on Iraq shows that "small-scale [projects], local aid spending ... reduces conflict by creating incentives for average citizens to support the government in subtle ways.

[45] In Zimbabwe in 2003, Human Rights Watch documented examples of residents being forced to display ZANU-PF Party membership cards before being given government food aid.

Related findings[49] of Beath, Christia, and Enikolopov further demonstrate that a successful community-driven development program increased support for the government in Afghanistan by exacerbating conflict in the short term, revealing an unintended consequence of the aid.

[50] However, there is no clear consensus on the trade-offs between speed and control, especially in emergency situations when the humanitarian imperative of saving lives and alleviating suffering may conflict with the time and resources required to minimise corruption risks.

Adjustment to normal life again can be a problem, with feelings such as guilt being caused by the simple knowledge that international aid workers can leave a crisis zone, whilst nationals cannot.

A 2015 survey conducted by The Guardian, with aid workers of the Global Development Professionals Network, revealed that 79 percent experienced mental health issues.

[71] Most notably, it has replaced the core standards of the Sphere Handbook[72] and it is regularly referred to and supported by officials from the United Nations, the EU, various NGOs and institutes.

[76][77] In 1854, when the Crimean War began[78] Florence Nightingale and her team of 38 nurses arrived to Barracks Hospital of Scutari where there were thousands of sick and wounded soldiers.

[81][83] The most well-known origin story of formalized humanitarian aid is that of Henri Dunant, a Swiss businessman and social activist, who upon seeing the sheer destruction and inhumane abandonment of wounded soldiers from the Battle of Solferino in June 1859, canceled his plans and began a relief response.

His graphic account of the immense suffering he witnessed, written in his book A Memory of Solferino, became a foundational text to modern humanitarianism.

To start, Dunant was able to profoundly stir the emotions of his readers by bringing the battle and suffering into their homes, equipping them to understand the current barbaric state of war and treatment of soldiers after they were injured or killed; in of themselves these accounts altered the course of history.

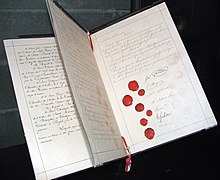

[88] After publishing his foundational text in 1862, progress came quickly for Dunant and his efforts to create a permanent relief society and International Humanitarian Law.

Composed of five Geneva citizens, this committee endorsed Dunant's vision to legally neutralize medical personnel responding to wounded soldiers.

The significance only grew with time in the revision and adaptation of the Geneva Convention in 1906, 1929 and 1949; additionally, supplementary treaties granted protection to hospital ships, prisoners of war and most importantly to civilians in wartime.

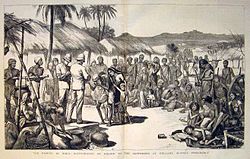

In 1876, after a drought led to cascading crop failures across Northern China, a famine broke out that lasted several years—during its course as many as 10 million people may have died from hunger and disease.

[98] British missionary Timothy Richard first called international attention to the famine in Shandong in the summer of 1876 and appealed to the foreign community in Shanghai for money to help the victims.

The Shandong Famine Relief Committee was soon established, with those participating including diplomats, businessmen, as well as Christian missionaries, Catholic and Protestant alike.

Retrospectively, authorities from across the administrative and colonial structures of the British Raj and princely states have been to various degrees blamed for the shocking severity of the famine, with critiques revolving around their laissez-faire attitude and the resulting lack of any adequate policy to address the mass death and suffering across the subcontinent, though meaningful relief measures began to be introduced towards the famine's end.

Despite the ongoing ideological, material, and military conflicts levied by both the new socialist state and the capitalist international community towards one another, efforts to aid the starving population of Soviet Russia were intensive, deliberate, and effective.

It was only in the 1980s, that global news coverage and celebrity endorsement were mobilized to galvanize large-scale government-led famine (and other forms of) relief in response to disasters around the world.