Foot binding

In the story, Pan Yunu, renowned for having delicate feet, performed a dance barefoot on a floor decorated with the design of a golden lotus.

[2] Li Yu created a 1.8-meter-tall (6 ft) golden lotus decorated with precious stones and pearls and asked his concubine Yao Niang (窅娘) to bind her feet in white silk into the shape of the crescent moon.

"[12] In the 13th century, scholar Che Ruoshui [zh] wrote the first known criticism of the practice: "Little girls not yet four or five years old, who have done nothing wrong, nevertheless are made to suffer unlimited pain to bind [their feet] small.

[12] The style of bound feet found in Song dynasty tombs, where the big toe was bent upwards, appears to be different from the norm of later eras—an ideal known as the 'three-inch golden lotus'—may be a later development in the 16th century.

[22][23][24] As foot binding restricted the movement of a woman, one side effect of its rising popularity was the corresponding decline of the art of women's dance in China, and it became increasingly rare to hear about beauties and courtesans who were also great dancers after the Song era.

[25][26] The Manchus issued a number of edicts to ban the practice, first in 1636 when the Manchu leader Hong Taiji declared the founding of the new Qing dynasty, then in 1638, and another in 1664 by the Kangxi Emperor.

[27] In late 19th century Guangdong it was customary to bind the feet of the eldest daughter of a lower-class family who was intended to be brought up as a lady.

Women, their families and their husbands took great pride in tiny feet, with the ideal length, called the 'Golden Lotus', being about three Chinese inches (寸) long—around 11 cm (4.3 in).

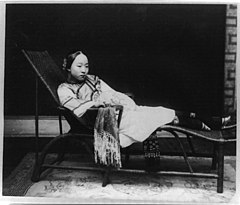

[31] Contrary to missionary writings, many women with bound feet were able to walk and work in the fields, albeit with greater limitations than their non-bound counterparts.

Women with bound feet in one village in Yunnan Province formed a regional dance troupe to perform for tourists in the late 20th century, though age has since forced the group to retire.

[34][35] However the rebellion failed and Christian missionaries, who had provided education for girls and actively discouraged what they considered a barbaric practice that had deleterious social effect on women,[36] then played a part in changing elite opinion on foot binding through education, pamphleteering and lobbying of the Qing court,[37][38] as no other culture in the world practised the custom of foot binding.

Kang Youwei submitted a petition to the throne commenting on the fact that China had become a joke to foreigners and that "footbinding was the primary object of such ridicule.

"[50] Reformers such as Liang Qichao, influenced by Social Darwinism, also argued that it weakened the nation, since enfeebled women supposedly produced weak sons.

[71] A less severe form in Sichuan, called "cucumber foot" (huángguā jiǎo 黃瓜腳) due to its slender shape, folded the four toes under but did not distort the heel or taper the ankle.

[78] The Manchus, wanting to emulate the particular gait that bound feet necessitated, adapted their own form of platform shoes to cause them to walk in a similar swaying manner.

[83] In southern China, in Canton (Guangzhou), 19th-century Scottish scholar James Legge noted a mosque that had a placard denouncing foot binding, saying Islam did not allow it since it constituted violating the creation of God.

It was generally an elder female member of the girl's family or a professional footbinder who carried out the initial breaking and ongoing binding of the feet.

[89] Disease inevitably followed infection, meaning that death from septic shock could result from foot binding, and a surviving girl was more at risk of medical problems as she grew older.

These scientific investigations detailed how foot binding deformed the leg, covered the skin with cracks and sores and altered the posture.

The interpretive models used include fashion (with the Chinese customs somewhat comparable to the more extreme examples of Western women's fashion such as corsetry), seclusion (sometimes evaluated as morally superior to the gender mingling in the West), perversion (the practice imposed by men with sexual perversions), inexplicable deformation, child abuse and extreme cultural traditionalism.

In the late 20th century some feminists introduced positive overtones, reporting that it gave some women a sense of mastery over their bodies and pride in their beauty.

[95] Before foot binding was practised in China, admiration for small feet already existed as demonstrated by the Tang dynasty tale of Ye Xian written around 850 by Duan Chengshi.

[99][100] Even while not much was written on the subject of foot binding prior to the latter half of the 19th century, the writings that were done on this topic, particularly by educated men, frequently alluded to the erotic nature and appeal of bound feet in their poetry.

[39] A common argument is that it was the result of the revival of Confucianism as neo-Confucianism and that, in addition to promoting the seclusion of women and the cult of widow chastity, it also contributed to the development of foot binding.

[108] However, historian Patricia Ebrey suggests that this story might be fictitious,[110] and argued that the practice arose so as to emphasize the gender distinction during a period of societal change in the Song dynasty.

[117] The practice was carried out only by women on girls, and it served to emphasize the distinction between male and female, an emphasis that began from an early age.

[126] The early Chinese feminist Qiu Jin, who underwent the painful process of unbinding her own bound feet, attacked foot binding and other traditional practices.

She believed that women should emancipate themselves from oppression, that girls could ensure their independence through education, and that they should develop new mental and physical qualities fitting for the new era.

[130][131] This argument has been challenged by John Shepherd in his book Footbinding as Fashion, and shows there was no connection between handicraft industries and the proportion of women bound in Hebei.

[133] John Shepherd provides a critical review of the evidence cited for the notion that foot binding was an expression of "Han identity" and rejects this interpretation.