Foreign exchange reserves

In terms of financial assets classifications, reserve assets can be classified as gold bullion, unallocated gold accounts, special drawing rights, currency, reserve position in the IMF, interbank position, other transferable deposits, other deposits, debt securities, loans, stocks (listed and unlisted), investment fund shares and financial derivatives, such as forward contracts and options.

Hence, in a world of perfect capital mobility, a country with fixed exchange rate would not be able to execute an independent monetary policy.

A central bank which chooses to implement a fixed exchange rate policy may face a situation where supply and demand would tend to push the value of the currency lower or higher (an increase in demand for the currency would tend to push its value higher, and a decrease lower) and thus the central bank would have to use reserves to maintain its fixed exchange rate.

Under perfect capital mobility, the change in reserves is a temporary measure, since the fixed exchange rate attaches the domestic monetary policy to that of the country of the base currency.

Non-sterilization will cause an expansion or contraction in the amount of domestic currency in circulation, and hence directly affect inflation and monetary policy.

Also, some central banks may let the exchange rate appreciate to control inflation, usually by the channel of cheapening tradable goods.

As a consequence, even those central banks that strictly limit foreign exchange interventions often recognize that currency markets can be volatile and may intervene to counter disruptive short-term movements (that may include speculative attacks).

Therefore, countries with similar characteristics accumulate reserves to avoid negative assessment by the financial market, especially when compared to members of a peer group.

As an example of regional framework, members of the European Union are prohibited from introducing capital controls, except in an extraordinary situation.

The dynamics of China's trade balance and reserve accumulation during the first decade of the 2000 was one of the main reasons for the interest in this topic.

Usually, the explanation is based on a sophisticated variation of mercantilism, such as to protect the take-off in the tradable sector of an economy, by avoiding the real exchange rate appreciation that would naturally arise from this process.

One attempt[13] uses a standard model of open economy intertemporal consumption to show that it is possible to replicate a tariff on imports or a subsidy on exports by closing the capital account and accumulating reserves.

In some cases, this could improve welfare, since the higher growth rate would compensate the loss of the tradable goods that could be consumed or invested.

The government, by closing the financial account, would force the private sector to buy domestic debt for lack of better alternatives.

Therefore, a central bank must continually increase the amount of its reserves to maintain the same power to manage exchange rates.

However, this may be less than the reduction in purchasing power of that currency over the same period of time due to inflation, effectively resulting in a negative return known as the "quasi-fiscal cost".

The caveat is that higher reserves can decrease the perception of risk and thus the government bond interest rate, so this measures can overstate the cost.

In the context of theoretical economic models it is possible to simulate economies with different policies (accumulate reserves or not) and directly compare the welfare in terms of consumption.

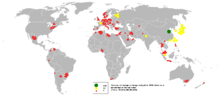

Of this year the countries significant by size of reserves were Austria-Hungary, Belgium, Canadian Confederation, Denmark, Grand Duchy of Finland, German Empire and Sweden-Norway.

Central banks throughout the world have sometimes cooperated in buying and selling official international reserves to attempt to influence exchange rates and avert financial crisis.

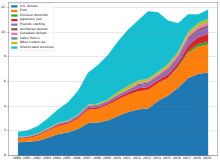

Historically, especially before the 1997 Asian financial crisis, central banks had rather meager reserves (by today's standards) and were therefore subject to the whims of the market, of which there was accusations of hot money manipulation, however Japan was the exception.

In the case of Japan, forex reserves began their ascent a decade earlier, shortly after the Plaza Accord in 1985, and were primarily used as a tool to weaken the surging yen.

[19] After 1997, nations in East and Southeast Asia began their massive build-up of forex reserves, as their levels were deemed too low and susceptible to the whims of the market credit bubbles and busts.

[citation needed] By 2007, the world had experienced yet another financial crisis, this time the US Federal Reserve organized central bank liquidity swaps with other institutions.

Developed countries authorities adopted extra expansionary monetary and fiscal policies, which led to the appreciation of currencies of some emerging markets.

The resistance to appreciation and the fear of lost competitiveness led to policies aiming to prevent inflows of capital and more accumulation of reserves.

Those liquidity needs are calculated taking in consideration the correlation between various components of the balance of payments and the probability of tail events.

Besides that, the Fund does econometric analysis of several factors listed above and finds those reserves ratios are generally adequate among emerging markets.

If those were included, Norway, Singapore and Persian Gulf States would rank higher on these lists, and United Arab Emirates' estimated $627 billion Abu Dhabi Investment Authority would be second after China.

[22] ECN is a unique electronic communication network that links different participants of the Forex market: banks, centralized exchanges, other brokers and companies and private investors.