Foreign relations of Tibet

Tibetan foreign relations during the Ming dynasty are opaque, with Tibet being either a tributary state or under full Chinese sovereignty.

[6] A stone monument dating to 823 and setting out the terms of peace and borders between Tibet and China arrived at in 821 can still be seen in front of the Jokhang temple in Barkhor Square in Lhasa.

It records the Sino-Tibetan treaty of 822 concluded by King Ralpacan and includes the following inscription: "Tibet and China shall abide by the frontiers of which they are now in occupation.

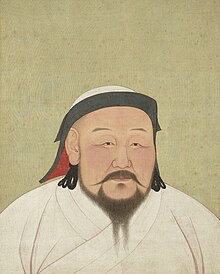

[11] After the Mongol Prince Köden took control of the Kokonor region in 1239, in order to investigate the possibility of attacking Song China from the West, he sent his general Doorda Darqan on a reconnaissance mission into Tibet in 1240.

The next year he was named Imperial Preceptor (Dishi) of the Yuan dynasty, and his position as titular ruler of Tibet (now in the form of its 13 myriarchies) was reconfirmed, while the Mongols managed a structural and administrative rule over the region.

The Yuan-Sakya hegemony over Tibet continued into the middle of the 14th century, although it was challenged by a revolt of the 'Bri-khung sect with the assistance of Hülegü of the Ilkhanate in 1285.

After the defeat of a first expeditionary force in the Battle of the Salween River in 1718 the Chinese expedition in 1720 was successful in restoring the Dalai Lama to power in Lhasa.

[13] China did not make any attempt to impose direct rule on Tibet and the Tibetan government around the Dalai Lama or his regent continued to manage its day-to-day affairs, thus in their own view remaining independent.

Declarations of independence made by the Dalai Lama were not recognized by Britain or China, but an effective military frontier was established which excluded troops and agents of the Chinese government until the invasion by the People's Liberation Army in 1950.

The principal motivation for the British mission was a fear, which proved to be unfounded, that Russia was extending its footprint into Tibet and possibly even giving military aid to the Tibetan government.

This was a failure with respect to China, which refused to assent to expansive Tibetan demands despite having no effective control, or even access, to most of the lands claimed by Tibet.

[34] By August, the Tibetans lost so much land to Liu Wenhui and Ma Bufang's forces that the Dalai Lama telegraphed the British government of India for assistance.

[39] Under orders from the Kuomintang government of Chiang Kai-shek, Ma Bufang repaired Yushu airport to prevent Tibetan separatists from seeking independence.

[citation needed] Chiang also ordered Ma Bufang to put his Muslim soldiers on alert for an invasion of Tibet in 1942.

[46] He was accompanied by Lieutenant Brooke Dolan II who had previously engaged in extensive naturalistic explorations in Tibet on behalf of the Philadelphia Academy of Natural Science.

[47] On their way to Lhasa the expedition made contact in Yatung with a member of the Pandatsang family of Kham which controlled Tibet's external wool trade, a major source of government revenue.

[48] A letter from Franklin Roosevelt was delivered which was carefully phrased as being addressed to the Dalai Lama as a religious leader but not as the ruler of Tibet.

[50] Tolstoy remained for three months but did not attempt to raise the question of transshipment of supplies to China as he could see the unfavorable attitude of the Tibetans.

This never came to fruition as both Britain and the United States, in consideration of their relations with China, continued to take the position that Tibet was not a sovereign country.

[59] The subject of Tibet arose briefly in international affairs in 1942-43 as a result efforts by the U.S. to fly aid to China over the Himalayas following the closure of the Burma Road.

The U.S. sent a mission to Lhasa led by Captain Ilya Tolstoy to study the possibility of an air supply route crossing Tibetan territory.

In 1995, US State Department reiterated its position during the hearing before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee: British Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden accordingly wrote a note presented to the Chinese government which describes Tibet as, "an autonomous State under the suzerainty of China" that "enjoyed de facto independence.

"[61] Meanwhile, the British embassy in Washington told the U.S. State Department that, "Tibet is a separate country in full enjoyment of local autonomy, entitled to exchange diplomatic representatives with other powers.

After a delay, perhaps occasioned by British diplomatic reluctance, they proceeded to Nanking where a carefully crafted letter to Chiang Kai-shek was presented which asserted an expansive claim of independence.

[65] The letters to the United States, after long delay, were translated and dispatched to Washington along with a favorable note from U.S. charge dé affairs in New Delhi which stressed the potential strategic importance of Tibet.

Washington was having none of that, however, and while encouraging scouting trips to Lhasa if the occasion should arise, deprecated efforts to establish a diplomatic relationship with Tibet.

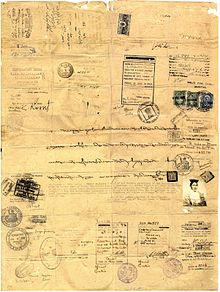

[66] In 1947 the Tibetan foreign office began planning a trade delegation to visit India, China, the United States and Britain.

Initial overtures were made to the US embassy in India requesting meetings with President Truman and other US officials to discuss trade.

This agreement was successfully put into effect in Tibet but in June 1956, rebellion broke out in the Tibetan populated borderlands of Amdo and Kham when the government tried to impose the socialist transformation policies in these regions that they had in other provinces of China.

The Battle of Chamdo in 1950 resulted in a flurry of diplomatic activity as Tibet attempted to negotiate with the Chinese government, appealed futilely to the international community, and then was forced to capitulate.