Fort King George

Problems such as periodic river flooding, indolence, starvation, excessive alcoholism, desertion, enemy threats, and potential mutiny exacerbated hardships at the fort.

Oglethorpe borrowed extensively from ideas laid out earlier when South Carolina imperialists, such as John Barnwell, Joseph Bowdler, and Francis Nicholson, planned Fort King George as part of a defensive system.

The park's museum focuses on the 18th-century cultural history of the area, including the Guale, the 17th-century Spanish mission Santo Domingo de Talaje, the fort, and the Scottish colonists.

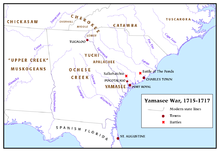

To curb French encroachment from the west, and to undermine Spain's traditional claims to areas north of Florida, the British colonists deemed it vital to expand and defend their southern borders, especially at the Savannah River.

[6][7] The imperial struggle contributed in the 1720s to the establishment of Fort King George by the British, built at the headwaters of the Altamaha River, 3 miles (5 km) inland from Sapelo Island.

The surviving mission Indians retreated and aggregated farther south until their remnants were situated just north of the Saint Augustine base near the St. Johns River.

"Projet Sur La Caroline", while never implemented, left the South Carolina colonists with high anxiety for many years, and convinced officials of the necessity to maintain good Indian alliances.

Finally, the Yamasee War had made many English officials realize that the preservation of South Carolina was principal in defending the British North American Empire.

Immediately upon landing the following March, the soldiers were placed in a hospital in Port Royal, South Carolina, where they would spend time recovering throughout the remainder of that year.

[64] Finally, in 1727, British Parliament ordered that Fort King George be abandoned and that the Independent Company be moved to Port Royal, South Carolina.

Writing with a clear hint of indignation, Massey complained about the poor provisions and indicated grave concern that the men may mutiny if "they have no hopes of being relieved."

As such, the struggles and failures of Fort King George showed future empire builders a better way of defense, thus lending much credit to them for heeding the old adage, "those who do not learn from history are destined to repeat it."

Oglethorpe and his fellow Georgians did not repeat the mistakes made in the handling of Fort King George, though they did largely stick to a similar plan of defense.

During Fort King George's existence and demise, the South Carolina Legislature, Governor, and other imperialists started developing other alternatives for defending the colony's vulnerable southern border.

However, though the project did fail, it was successful in drawing greater attention throughout England to the area and proved especially enticing to English philanthropists looking to provide some sort of refuge for poor debtors.

Once a group of Trustees was formed, they decided to use debtor-prisoners to people the colony of Georgia, which was to be nestled in the Savannah-Altamaha River region, formerly known as the Margravate of Azilla, based upon a previously failed settlement scheme in 1717.

This would allow them to escape the misfortune of Britain's harsh penal code and poverty, and to start over in a new land while simultaneously serving a valuable function for the British Crown.

In fact, most were middle-class artisans and craftsmen whose interests in starting life new abroad was so great, the earlier plan for a debtors’ colony ended up being quite changed.

Nevertheless, the colony was to be established as a haven for citizen-soldiers whose primary purpose was in defending the empire, while simultaneously contributing to her mercantilist economy as well with the production of cash crops, timber, furs, and naval stores.

The intense climate and harsh natural surroundings along the Altamaha, coupled with history, compelled Oglethorpe to seek a resilient group of people to settle the area.

Approximately one-third of all marshlands found on the east coast lie in coastal Georgia, which dips away from the continental shelf considerably farther than any other section of eastern North America.

Over years, this dramatic tidal shift has produced dynamic currents that have created a labyrinth of rivers, inlets, shoals, sounds, and sandbars contained behind ever-changing barrier islands.

Though clannish, often insular, and politically unstable at home, the Scots were a force to be reckoned with on the battlefield, a perfect ingredient for frontier defense in the wildernesses along the Georgia coast where conventional warfare was not going to be the norm.

Home life was rough due to English oppression and a feudal system that tied many Scottish families to small unproductive lands with limited opportunities, but North America offered plenty of hope.

They consisted of McIntoshes, McDonalds, MacBeans, MacKays, Frasers, Forbes, Clarks, Baillies, Cameron, and a host of other traditional Highland clan names.

In the ensuing years, they were integral in establishing a timber industry in Georgia as thousands of feet of lumber were shipped down the Altamaha River and processed at sawmills in Darien.

This successful battle helped bring to an end the struggle for empire in the Southeast and worked to cement Great Britain's hold on the area, as the Spanish never again really posed a serious threat to Georgia.

Crane's work about the contentious southern frontier was the first to describe the context for Fort King George and Barnwell's scheme of settling the Altamaha River region.

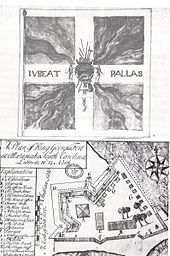

Lewis, or "Miss Bessie", as the locals fondly called her, discovered extensive material about the fort, including vital written records, descriptions, account ledgers, and several drawings with geographical details.

Georgia State Senator Renee Kemp, from 1999 to 2002, helped gain several hundred thousand dollars in capital investment for the site to reconstruct the fort's enlisted soldiers’ barracks, guardhouse, and officers’ quarters.