Fort Runyon

The forward march movement into Virginia, indicated in my despatches last night, took place at the precise time this morning that I named, but in much more imposing and powerful numbers.

The troops quartered at Georgetown, the Sixty-ninth, Fifth, Eighth and Twenty-eighth New York regiments, proceeded across what is known as the chain bridge, above the mouth of the Potomac Aqueduct, under the command of General McDowell.

Eight thousand infantry, two regular cavalry companies and two sections of Sherman's artillery battalion, consisting of two batteries, were in line this side of the Long Bridge at two o'clock.

Engineer officers under the command of then-Colonel John G. Barnard accompanied the army and began building fortifications and entrenchments along the banks of the Potomac River in order to defend the bridges that crossed it.

Men from these regiments supplied the labor involved in the construction of Fort Runyon, while engineers under Colonel Barnard's command directed the work.

[13] The land for the fort was appropriated from James Roach, a building contractor in Washington who was the second-largest landowner in the county, behind only the Lee family.

Roach's mansion on Prospect Hill was vandalized by Union forces during the construction of Fort Runyon, but survived the war and was demolished in 1965.

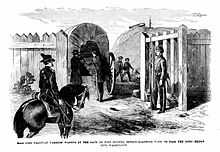

[17] Large gates were built into the two southernmost walls in order to provide passage for wagons and passengers traveling along the two turnpikes that linked to the Long Bridge.

Fort Runyon was built directly at the crossroads of the two turnpikes, and served as a checkpoint for vehicles entering the city via the Long Bridge.

Colonel Barnard directed individual engineers and small groups to survey likely sites for forts even before Virginia seceded from the United States.

By the time Barnard was beginning to focus his efforts on tying the two forts into an entire interlocking system of fortifications, his engineers were drawn off by the approach of the Confederate Army and the incipient Battle of Bull Run.

[20] Following the Union defeat at Bull Run, panicked efforts were made to strengthen the forts built by Barnard in order to defend Washington from what was perceived as an imminent Confederate attack.

[24] The defenses south of the Potomac were combined into the Arlington Line, an interlocking system of forts, blockhouses, rifle pits and trenches that would defend Washington throughout the entire course of the war.

Their intimidating nature was designed to dissuade an attack as much as repel one,[25] and over the four years that would pass before the final armistice, no Confederate force would ever seriously attempt to penetrate the Arlington Line.

Officers and men alike reunited at the fort, only to be reassigned to hurried entrenchment efforts in order to prevent a threatened Confederate march on Washington.

A total of 41 men were convicted of dereliction of duty and imprisoned in Fort Jefferson in the Dry Tortugas before eventually agreeing to satisfactorily complete their enlistments.

"[33] After the surrender of General Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia on April 9, 1865, the primary reason for manned defenses protecting Washington ceased to exist.

Due to its proximity to Washington and the large influx of freed blacks to the city that followed the end of the Civil War, the fort became residence to many squatters, most of whom were African-American.

Needy negro squatters, living around the forts, have built themselves shanties of the officers' quarters, pulled out the abatis for firewood, made cord wood or joists out of the log platforms for the guns, and sawed up the great flag-staffs into quilting poles or bedstead posts.

A 1901 Rand McNally tour guide of Washington instructs tourists to look out of the windows of their train at the south end of the Long Bridge to catch a glimpse of the decaying fort.

"At its further end there still stands, plainly seen at the left of the track as soon as the first high ground is reached, Fort Runyon, a strong earthwork erected in 1861 to guard the head of the bridge from raiders.

"[36] A brickworks was also located nearby, sometimes utilizing the clay that formed the bastions of Fort Runyon as raw material for the bricks that would later go into the walls of Washington homes.

The approach routes to the bridges ran directly through the earthworks of the old fort, and these were leveled in order to provide smooth passage for trains and automobiles.