Fort Ticonderoga

The mountains created nearly impassable terrains to the east and west of the Great Appalachian Valley that the site commanded.

The British controlled the fort at the beginning of the Revolutionary War, but the Green Mountain Boys and other state militia under the command of Ethan Allen and Benedict Arnold captured it on May 10, 1775.

Henry Knox led a party to transport many of the fort's cannon to Boston to assist in the siege against the British, who evacuated the city in March 1776.

The only direct attack on the fort during the Revolution took place in September 1777, when John Brown led 500 Americans in an unsuccessful attempt to capture it from about 100 British defenders.

[5] In 1642, French missionary Isaac Jogues was the first white man to traverse the portage at Ticonderoga while escaping a battle between the Iroquois and members of the Huron tribe.

[6] The French, who had colonized the Saint Lawrence River valley to the north, and the English, who had taken over the Dutch settlements that became the Province of New York to the south, began contesting the area as early as 1691, when Pieter Schuyler built a small wooden fort at the Ticonderoga point on the western shore of the lake.

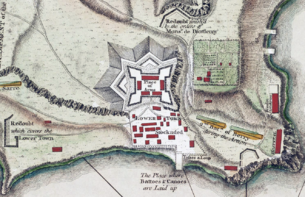

[12][13] The work in 1755 consisted primarily of beginning construction on the main walls and on the Lotbinière redoubt, an outwork to the west of the site that provided additional coverage of La Chute River.

Consequently, its most important defenses, the Reine and Germaine bastions, were directed to the northeast and northwest, away from the lake, with two demi-lunes further extending the works on the land side.

Still, General Montcalm and two of his military engineers surveyed the works in 1758 and found something to criticize in almost every aspect of the fort's construction; the buildings were too tall and thus easier for attackers' cannon fire to hit, the powder magazine leaked, and the masonry was of poor quality.

[24] In June 1758, British General James Abercromby began amassing a large force at Fort William Henry in preparation for a military campaign directed up the Champlain Valley.

[25] The French general Louis-Joseph de Montcalm, who had only arrived at Carillon in late June, engaged his troops in a flurry of work to improve the fort's outer defenses.

Abercromby tried to move rapidly against the few French defenders, opting to forgo field cannon and relying instead on the numerical superiority of his 16,000 troops.

[29] The battle gave the fort a reputation for impregnability, which affected future military operations in the area, notably during the American Revolutionary War.

[37] On May 10, 1775, less than one month after the Revolutionary War was ignited with the battles of Lexington and Concord, the British garrison of 48 soldiers was surprised by a small force of Green Mountain Boys, along with militia volunteers from Massachusetts and Connecticut, led by Ethan Allen and Benedict Arnold.

[39] With the capture of the fort, the Patriot forces obtained a large supply of cannons and other armaments, much of which Henry Knox transported to Boston during the winter of 1775–1776.

Benedict Arnold remained in control of the fort until 1,000 Connecticut troops under the command of Benjamin Hinman arrived in June 1775.

Under the leadership of generals Philip Schuyler and Richard Montgomery, men and materials for the invasion were accumulated there through July and August.

[45] The British chased the American forces back to Ticonderoga in June and, after several months of shipbuilding, moved down Lake Champlain under Guy Carleton in October.

[30] This, combined with continuing incursions up the Hudson River valley by British forces occupying New York City, led Washington to believe that any attack on the Albany area would be from the south, which, as it was part of the supply line to Ticonderoga, would necessitate a withdrawal from the fort.

Colonel John Brown led the troops on the west side, with instructions to release prisoners if possible, and attack the fort if it seemed feasible.

[64] The fort's occupants were unaware of the action until Brown's men and British troops occupying the old French lines skirmished.

[65] A stalemate persisted, with regular exchanges of cannon fire, until September 21, when 100 Hessians, returning from the Mohawk Valley to support Burgoyne, arrived on the scene to provide reinforcement to the besieged fort.

[68] The fort was occasionally reoccupied by British raiding parties in the following years, but it no longer held a prominent strategic role in the war.

[69] In the years following the war, area residents stripped the fort of usable building materials, even melting some of the cannons down for their metal.

The ceremonies, which commemorated the 300th anniversary of the discovery of Lake Champlain by European explorers, were attended by President William Howard Taft.

[79] Designated as a National Historic Landmark by the Department of Interior, the fort is now operated by the foundation as a tourist attraction, early American military museum, and research center.

[80] The fort has been on a watchlist of National Historic Landmarks since 1998, because of the poor condition of some of the walls and of the 19th-century pavilion constructed by William Ferris Pell.

In 2008, the powder magazine, destroyed by the French in 1759, was reconstructed by Tonetti Associates Architects,[81] based in part on the original 1755 plans.

[83] The not-for-profit Living History Education Foundation conducts teacher programs at Fort Ticonderoga during the summer that last approximately one week.

The program trains teachers how to teach Living History techniques, and to understand and interpret the importance of Fort Ticonderoga during the French and Indian War and the American Revolution.