German invasion of the Netherlands

[8] On 9 October, Adolf Hitler ordered plans to be made for an invasion of the Low Countries, to use them as a base against Great Britain and to pre-empt a similar attack by the Allied forces, which could threaten the vital Ruhr Area.

[14] Hendrikus Colijn, Prime Minister of the Netherlands between 1933 and 1939, was personally convinced that Germany would not violate Dutch neutrality;[15] senior officers made no effort to mobilise public opinion in favour of improving military defence.

[24] The Dutch government never officially formulated a policy on how to act in case of either contingency; the majority of ministers preferred to resist an attack, while a minority and Queen Wilhelmina refused to become a German ally whatever the circumstances.

It functioned as a National Redoubt, which was expected to hold out a prolonged period of time,[68] in the most optimistic predictions as much as three months without any allied assistance,[69] even though the size of the attacking German force was strongly overestimated.

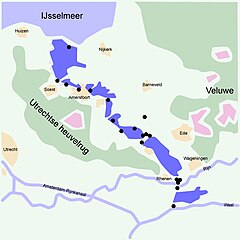

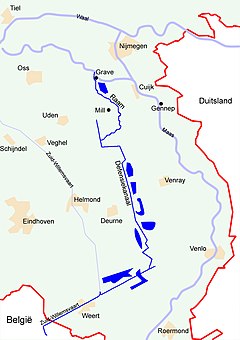

[70] Before the war the intention was to fall back to this position almost immediately, after a concentration phase (the so-called Case Blue) in the Gelderse Valley [fy; li; nds-nl; nl; zea],[71] inspired by the hope that Germany would only travel through the southern provinces on its way to Belgium and leave Holland proper untouched.

This second main defensive position had a northern part formed by the Grebbelinie (Grebbe line), located at the foothills of the Utrechtse Heuvelrug, an Ice Age moraine between Lake IJssel and the Lower Rhine.

[73] This line was extended by a southern part: the Peel-Raamstelling (Peel-Raam Position), located between the Maas and the Belgian border along the Peel Marshes and the Raam River, as ordered by the Dutch Commander in Chief, General Izaak H. Reijnders.

He proposed a shift to a more mobile strategy by fighting a delaying battle at the plausible crossing sites near Arnhem and Gennep to force the German divisions to spend much of their offensive power before they had reached the MDL, and ideally even defeat them.

[89] The French Commander in Chief General Maurice Gamelin was more than interested in including the Dutch in his continuous front as—like Major-General Bernard Montgomery four years later—he hoped to circle around the Westwall when the Entente launched its planned 1941 offensive.

He therefore reassigned the former French strategic reserve, the 7th Army, to operate in front of Antwerp to cover the river's eastern approaches in order to maintain a connection with the Fortress Holland further to the north and preserve an allied left flank beyond the Rhine.

[94] Although the French troops would have a higher proportion of motorised units than their German adversaries, in view of the respective distances to be covered, they could not hope to reach their assigned sector advancing in battle deployment before the enemy did.

The German divisions, with a nominal strength of 17,807 men, were fifty percent larger than their Dutch counterparts and possessed twice their effective firepower, but even so the necessary numerical superiority for a successful offensive was simply lacking.

[99] As both efforts were unlikely to succeed, the mass of regular divisions was reinforced by the SS-Verfügungsdivision (including SS-Standarten Der Führer, Deutschland and Germania) and Leibstandarte Adolf Hitler, which would serve as assault infantry to breach the Dutch fortified positions.

[115] Though he indicated a German armoured division would try to attack Fortress Holland from North Brabant and that there was a plan to capture the Queen, Dutch defensive strategy was not adapted and it was not understood these were elements of a larger scheme.

[131] The Germans, executing a plan approved by Hitler,[132] tried to capture the IJssel and Maas bridges intact, using commando teams of Brandenburgers that began to infiltrate over the Dutch border ahead of the main advance, with some troops arriving on the evening of 9 May.

[137] This withdrawal was originally planned for the first night after the invasion, under cover of darkness, but due to the rapid German advance an immediate retreat was ordered at 06:45, to avoid the 3rd Army Corps becoming entangled with enemy troops.

When a first attack by forward elements had been repulsed, a full assault at the Main Defense Line was initially postponed to the next day because most artillery had not yet passed the single pontoon bridge over the Meuse, which had caused a traffic jam after having been damaged by an incident.

Winkelman, sensitive to the general Dutch weakness in the region, requested the British government to send an Army Corps to reinforce allied positions in the area and bomb Waalhaven airfield.

[169] Shortly after noon German armoured cars had penetrated thirty kilometres further to the west and made contact with the southern Moerdijk bridgehead, cutting off Fortress Holland from the Allied main force; at 16:45 they reached the bridges themselves.

[180] In the North, the Wons Position formed a bridgehead at the eastern end of the Enclosure Dike; it had a long perimeter of about nine kilometres to envelop enough land to receive a large number of retreating troops without making them too vulnerable to air attack.

[185] When this had been denied by chief of staff Franz Halder, he had arranged the formation of an extra Army Corps headquarters to direct the complex strategic situation of simultaneously fighting the Allies and advancing into the Fortress Holland over the Moerdijk bridges.

[175] The bridge was reached and the remaining fifty German defenders in the building in front of it were on the point of surrender when after hours of fighting the attack was abandoned because of heavy flanking fire from the other side of the river.

[181] This dam was blocked by the Kornwerderzand Position, which protected a major sluice complex regulating the water level of Lake IJssel, which had to be sufficiently high to allow many Fortress Holland inundations to be maintained.

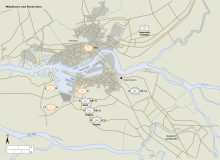

[225] Generals Kurt Student and Schmidt desired a limited air attack to temporarily paralyse the defences, allowing the tanks to break out of the bridgehead; severe urban destruction was to be avoided as it would only hamper their advance.

[229] At 09:00 a German messenger crossed the Willemsbrug to bring an ultimatum from Schmidt to Colonel Pieter Scharroo, the Dutch commander of Rotterdam, demanding a capitulation of the city; if a positive answer had not been received within two hours the "severest means of annihilation" would be employed.

Not feeling inclined to surrender regardless, he asked Winkelman for orders; the latter, hearing that the document had not been signed nor contained the name of the sender, instructed him to send a Dutch envoy to clarify matters and gain time.

[241] Winkelman concluded that it apparently had become the German policy to devastate any city offering any resistance; in view of his mandate to avoid unnecessary suffering and the hopelessness of the Dutch military position he decided to surrender.

The morale of the defenders of the Bath Position, already shaken by stories from Dutch troops fleeing to the west, was severely undermined by the news that Winkelman had surrendered; many concluded that it was useless for Zealand to continue resisting as the last remaining province.

[258] On 16 May SS-Standarte Deutschland, several kilometres to the west of the Zanddijk Position, approached the Canal through Zuid-Beveland, where the French 271e Régiment d’Infanterie was present, only partly dug in and now reinforced by the three retreated Dutch battalions.

In the evening the encroaching Germans threatened to overrun the French forces that had fled into Flushing, but a gallant delaying action led by brigade-general Marcel Deslaurens in person, in which he was killed, allowed most troops to be evacuated over the Western Scheldt.