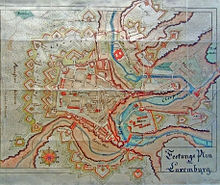

Fortress of Luxembourg

The fortress was of great strategic importance for the control of the Left Bank of the Rhine, the Low Countries, and the border area between France and Germany.

By the end of the Renaissance, Luxembourg was already one of Europe's strongest fortresses, but it was the period of great construction in the 17th and 18th centuries that gave it its fearsome reputation.

In 1795, the city, expecting imminent defeat and for fear of the following pillages and massacres, surrendered after a seven-month blockade and siege by the French, with most of its walls still unbreached.

[3][4] After the Romans had left, the fortification fell into disrepair, until in 963 Count Siegfried of the House of Ardennes acquired the land in exchange for his territories in Feulen near Ettelbrück from St. Maximin's Abbey in Trier.

Knights and soldiers were billeted here on the rocky outcrop, while artisans and traders settled in the area beneath it, creating the long-standing social distinction between the upper and the lower city.

[7]: 11 After the successful siege by Louis XIV in 1683-1684, French troops retook the fortress under the renowned commander and military engineer Sébastien Le Prestre de Vauban.

[5] Advance fortifications were placed on the heights around the city: the crownwork on Niedergrünewald, the hornwork on Obergrünewald, the "Corniche de Verlorenkost", Fort Bourbon and several redoubts.

[7]: 11 He greatly expanded the military's hold over the urban space by integrating Pfaffenthal into the defences, and large barracks were built on the Rham and Saint-Esprit plateaux.

In 1713 the Treaty of Utrecht gave Luxembourg to the Dutch, who ruled there for two more years before the fortress was retaken by Austrian troops in 1715, who remained in possession almost for the rest of the century.

[5] In the aftermath of Napoleon's final defeat in 1815, the Congress of Vienna elevated Luxembourg to a Grand Duchy, now ruled in personal union by the King of the Netherlands.

The stand-off was resolved in 1839, when the Treaty of London awarded the western part of Luxembourg to Belgium, while the rest, including the fortress, remained under William I.

After the war, the French offered King William III 5,000,000 guilder for his personal possession of Luxembourg, which the cash-strapped Dutch monarch accepted in March 1867.

In Luxembourg, however, an urgent desire to comply with the Treaty of London and a fear of being caught up in a future Franco-German war prompted the government to spearhead the project on behalf of the city.

The process was somewhat chaotic: often parts of the fortress were simply blown up, the usable materials carried off by local residents, and the rest was covered up with earth.

[7] The Spanish government fully recognised that sealing off the city would stifle the economy and result in depopulation at a time when large numbers of civilians were needed to provide for the supply and lodging of the troops.

[7] The fortress found itself encircled by a kind of no man's land, as the Austrians implemented a security perimeter in 1749, forbidding permanent constructions within.

Commander Neipperg had the earth removed down to the rock, a distance of 600 m (2,000 ft) from the fortress, so that attackers laying siege would have no opportunity to dig trenches.

Land expropriations often occurred without discussion, with the military invoking the threat of war and a state of emergency to seize plots without compensation.

The primary concern for military authorities was the persistent problem of troop desertion, a constant plague for all Ancien Régime garrisons.

[11]: 14 Living in a fortress city had serious disadvantages; the ramparts set strict limits on the amount of space available, while the inhabitants had to share this small area with large numbers of troops.

In times of crisis or war, the garrison might be increased dramatically, as in 1727-1732 when the Austrians feared a French attack and 10,000 soldiers were stationed inside the fortress or in camps in the surroundings (with the civilian population numbering only 8,000).

These people, who barely carved out a living from one week to the next, only just had enough beds to sleep in themselves, never mind providing accommodation for a large number of soldiers who were "crammed one on top of the other, experiencing first-hand the poverty and misery of their landlords".

Complaints still arose in the 18th century about Austrian officers who moved into rooms more spacious than the ones they had been assigned; others would bring women of low repute to their house at night, to the alarm of their civilian landlords.

The government claimed that since the garrison's presence brought trade and business which benefited the city's merchants and artisans, it was only fair for citizens to contribute by lodging the troops.

This led to abuses of power: the authorities were known to assign excessive numbers of soldiers to houses of residents who had been involved in disputes with the city.

Even in Prussian times in the 19th century, most officers rented a room with their "servis", their accommodation allowance, ensuring house-owners at least received payment.

[16] Both groups suffered the same poor living conditions in the city, such as the lack of a clean water supply and of sanitation, leading to outbreaks of cholera and typhus.

Straw posed a problem due to fire hazards, leading to its storage either in the trenches of the Front of the plain, in Pfaffenthal, or in the lower quarters of the Grund and Clausen.

In 1598, Georg Braun and Franz Hogenberg published the oldest known view of Luxembourg City, a copper engraving that appeared in Civitates orbis terrarum (Cologne, 1598).

Half a century later, the Dutch cartographer Joan Blaeu, drawing on Braun's work, published his "Luxemburgum" in the second volume of his Stedeboek (Amsterdam, 1649).