Fossils of the Burgess Shale

Stephen Jay Gould's 1989 book Wonderful Life describes the history of discovery up to the early 1980s, although his analysis of the implications for evolution has been contested.

[1] From late August to early September 1909, his team, including his family, collected fossils there, and in 1910 Walcott opened a quarry that he and his colleagues re-visited in 1911, 1912, 1913, 1917 and 1924, bringing back over 60,000 specimens in total.

[7][8] Beginning in the early 1970s Harry Whittington, his associates David Bruton and Christopher Hughes, and his graduate students Derek Briggs and Simon Conway Morris began a thorough re-examination of Walcott's collection.

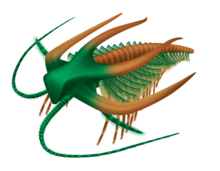

[10] The continuing search for Burgess Shale fossils since the mid-1970s has led to the description in the 1980s of an arthropod Sanctacaris[11] and in 2007 of Orthrozanclus, which looked like a slug with a small shell at the front, chain mail over the back and long, curved spines round the edges.

[13] They have also unearthed more and sometimes better fossils of animals that were discovered earlier, for example Odontogriphus was for many years known from just one poorly preserved specimen, but the discovery of a further 189 formed the basis for a detailed description and analysis in 2006.

[18] The deposits were originally laid down on the floor of a shallow sea; during the Late Cretaceous Laramide orogeny, mountain-building processes squeezed the sediments upwards to their current position at around 2,500 metres (8,000 ft) elevation[5] in the Rocky Mountains.

[13] The processes responsible for preserving the exceptional quality of the Burgess Shale fossils are unclear, due partly to two related issues: whether the animals were buried where they lived (or may have been carried long distances by sediment flows), or whether the water at the burial sites was anoxic, limiting the effect of oxygen on degradation.

The traditional view is that soft bodies and organs could only be preserved in anoxic conditions, otherwise oxygen-breathing bacteria would have made decomposition too rapid for fossilization.

One of their main reasons was that many fossils represented partially decayed soft-bodied animals such as polychaetes, which had already died shortly before the burial event, and would have been fragmented if they had been transported any significant distance by a storm of swirling sediment.

Morania appears on about a third of the slabs Caron and Jackson studied, and in some cases presents the wrinkled "elephant skin" texture typical of fossilized microbial mats.

[28][29] As of 2008[needs update]only two in-depth studies of the mix of fossils in any part of the Burgess Shale had been published, by Simon Conway Morris in 1986 and by Caron and Jackson in 2008.

[13] These patterns – a few common species and many rare ones; the dominance of arthropods and sponges; and the percentage frequencies of different life-styles – seem to apply to all of the Burgess Shale.

[13] Some recently discovered species, known in 2008 only by nicknames like "woolly bear" and "Siamese lantern" are familiar to the collecting teams, but have yet to be formally described and named.

[44] In 2009 Hagadorn found that anomalocarid mouthparts showed little wear, which suggests they did not come into regular contact with mineralised trilobite shells.

[39] In 2009 a fossil named Schinderhannes bartelsi, an apparent relative of Anomalocaris, was found in the Early Devonian period, about 100 million years later than the Burgess Shale.

[46] Conway Morris gave Hallucigenia its name because in his reconstruction it looked bizarre – a worm-like animal that walked on long, rigid spines and had a row of tentacles along its back.

[48] However, in the late 1980s Lars Ramsköld literally turned it over, so that the tentacles, which he found were paired, became legs and the spines were defensive equipment on its back.

[55] Supporters of the link with molluscs have stated that Wiwaxia shows no signs of segmentation, appendages in front of the mouth, or "legs—–all of which are typical polychaete features.

Conway Morris classified the Burgess Shale fossil Pikaia as a chordate because it had a rudimentary notochord, the rod of cartilage that evolved into the backbone of vertebrates.

[63] Doubts have been raised about this, because most of the important features are not quite like those of chordates: it has repeated blocks of muscle along its sides but they are not chevron-shaped; there is no clear evidence of anything like gills; and its throat appears to be in the upper part of its body rather than the lower.

[63] While Pikaia was celebrated in the mid-1970s as the earliest known chordate,[66] three jawless fish have since been found among the Chengjiang fossils, which are about 17 million years older than the Burgess Shale.

Although priapulid-like worms from various Cambrian deposits are often referred to Ottoia on spurious grounds, the only clear macrofossils of this genus come from the Burgess Shale.

English geologist and palaeontologist William Buckland (1784–1856) realised that a dramatic change in the fossil record occurred around the start of the Cambrian period, 539 million years ago.

Charles Darwin regarded the solitary existence of Cambrian trilobites and total absence of other intermediate fossils as the "gravest" problem to his theory of natural selection, and he devoted an entire chapter of The Origin of Species on the matter.

Fossils from the Ediacaran period, immediately preceding the Cambrian, were first found in 1868, but scientists at that time assumed there was no Precambrian life and therefore dismissed them as products of physical processes.

[76] Darwin's view – that gaps in the fossil record accounted for the apparently sudden appearance of diverse life forms – still had scientific support over a century later.

In the early 1970s Wyatt Durham and Martin Glaessner both argued that the animal kingdom had a long Proterozoic history that was hidden by the lack of fossils.

[76][77] However, Preston Cloud held a different view about the origins of complex life, writing in 1948 and 1968 that the evolution of animals in the Early Cambrian was "explosive".

[82] It appears that most of the major animal lineages had arisen before the time of the Burgess Shale, and before that of the Chengjiang and Sirius Passet lagerstätten about 15 million years earlier, in which very similar fossils are found,[65] and that the Cambrian explosion was complete by then.

[83][84] By 1996, with new fossil discoveries filling in some of the gaps in the "family tree", some Burgess Shale "weird wonders" such as Hallucinogenia and Opabinia were seen as stem members of a total group that included arthropods and some other living phyla.

- — = Lines of descent

- = Basal node

- = Crown node

- = Total group

- = Crown group

- = Stem group