Classical element

The classical elements typically refer to earth, water, air, fire, and (later) aether which were proposed to explain the nature and complexity of all matter in terms of simpler substances.

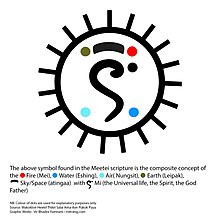

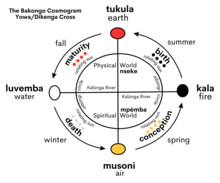

[1][2] Ancient cultures in Greece, Angola, Tibet, India, and Mali had similar lists which sometimes referred, in local languages, to "air" as "wind", and to "aether" as "space".

Empedoclean elements fire · air water · earth The ancient Greek concept of four basic elements, these being earth (γῆ gê), water (ὕδωρ hýdōr), air (ἀήρ aḗr), and fire (πῦρ pŷr), dates from pre-Socratic times and persisted throughout the Middle Ages and into the Early modern period, deeply influencing European thought and culture.

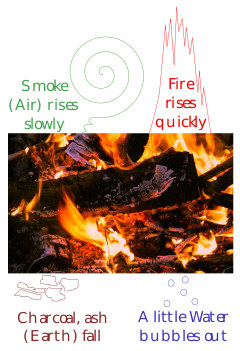

Themistius, the Aristotelian of the party, says:[11] If You but consider a piece of green-Wood burning in a Chimney, You will readily discern in the disbanded parts of it the four Elements, of which we teach It and other mixt bodies to be compos’d.

The fire discovers it self in the flame ... the smoke by ascending to the top of the chimney, and there readily vanishing into air ... manifests to what Element it belongs and gladly returnes.

The water ... boyling and hissing at the ends of the burning Wood betrayes it self ... and the ashes by their weight, their firiness, and their dryness, put it past doubt that they belong to the Element of Earth.According to Galen, these elements were used by Hippocrates (c. 460 – c. 370 BC) in describing the human body with an association with the four humours: yellow bile (fire), black bile (earth), blood (air), and phlegm (water).

[19] It had previously been believed by pre-Socratics such as Empedocles and Anaxagoras that aether, the name applied to the material of heavenly bodies, was a form of fire.

The Neoplatonic philosopher Proclus rejected Aristotle's theory relating the elements to the sensible qualities hot, cold, wet, and dry.

Fire is sharp (ὀξυτητα), subtle (λεπτομερειαν), and mobile (εὐκινησιαν) while its opposite, earth, is blunt (αμβλυτητα), dense (παχυμερειαν), and immobile (ακινησιαν[21]); they are joined by the intermediate elements, air and water, in the following fashion:[22]

A text written in Egypt in Hellenistic or Roman times called the Kore Kosmou ("Virgin of the World") ascribed to Hermes Trismegistus (associated with the Egyptian god Thoth), names the four elements fire, water, air, and earth.

The earliest Buddhist texts explain that the four primary material elements are solidity, fluidity, temperature, and mobility, characterized as earth, water, fire, and air, respectively.

The four properties are cohesion (water), solidity or inertia (earth), expansion or vibration (air) and heat or energy content (fire).

[35][36][34] Tibetan Buddhist theology, tantra traditions, and "astrological texts" also spoke of them making up the "environment, [human] bodies," and at the smallest or "subtlest" level of existence, parts of thought and the mind.

[34] Also at the subtlest level of existence, the elements exist as "pure natures represented by the five female buddhas", Ākāśadhātviśvarī, Buddhalocanā, Mamakī, Pāṇḍarāvasinī, and Samayatārā, and these pure natures "manifest as the physical properties of earth (solidity), water (fluidity), fire (heat and light), wind (movement and energy), and" the expanse of space.

The elemental system used in medieval alchemy was developed primarily by the anonymous authors of the Arabic works attributed to Pseudo Apollonius of Tyana.

These came from Indian Vastu shastra philosophy and Buddhist beliefs; in addition, the classical Chinese elements (五行, wu xing) are also prominent in Japanese culture, especially to the influential Neo-Confucianists during the medieval Edo period.

[43] The Islamic philosophers al-Kindi, Avicenna and Fakhr al-Din al-Razi followed Aristotle in connecting the four elements with the four natures heat and cold (the active force), and dryness and moisture (the recipients).

[44] The medicine wheel symbol is a modern invention attributed to Native American peoples dating to approximately 1972, with the following descriptions and associations being a later addition.

[50] Some modern scientists see a parallel between the classical elements and the four states of matter: solid, liquid, gas and weakly ionized plasma.

[52] The Dutch historian of science Eduard Jan Dijksterhuis writes that the theory of the classical elements "was bound to exercise a really harmful influence.

As is now clear, Aristotle, by adopting this theory as the basis of his interpretation of nature and by never losing faith in it, took a course which promised few opportunities and many dangers for science.