Four occupations

[15] Anthony J. Barbieri-Low, Professor of Early Chinese History at the University of California, Santa Barbara, writes that the classification of "four occupations" can be viewed as a mere rhetorical device that had no effect on government policy.

[19] Initially rising to power through controlling the new technology of bronzeworking, from 1300 BC, the shi transitioned from foot knights to being primarily chariot archers, fighting with composite recurved bow, a double-edged sword known as the jian, and armour.

[20] In the Battle of Bi, 597 BC, the routing chariot forces of Jin were bogged down in mud, but pursuing enemy troops stopped to help them get dislodged and allowed them to escape.

[22] As chariot warfare became eclipsed by mounted cavalry and infantry units with effective crossbowmen in the Warring States period, the participation of the shi in battle dwindled as rulers sought men with actual military training, not just aristocratic background.

[34] Beyond serving in the administration and the judiciary, scholar-officials also provided government-funded social services, such as prefectural or county schools, free-of-charge public hospitals, retirement homes and paupers' graveyards.

[35][36][37] Scholars such as Shen Kuo (1031–1095) and Su Song (1020–1101) dabbled in every known field of science, mathematics, music and statecraft,[38] while others like Ouyang Xiu (1007–1072) or Zeng Gong (1019–1083) pioneered ideas in early epigraphy, archeology and philology.

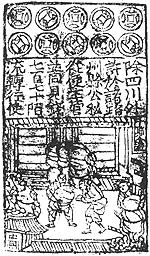

[42] Widespread printing through woodblock and movable type enhanced the spread of knowledge amongst the literate in society, enabling more people to become candidates and competitors vying for a prestigious degree.

William Rowe's research of rural elites in late imperial Hanyang, Hubei shows that there was a very high level of overlap and mixing between the gentry and the merchants.

[76] Historians like Yu Yingshi and Billy So have shown that as Chinese society became increasingly commercialized from the Song dynasty onward, Confucianism had gradually begun to accept and even support business and trade as legitimate and viable professions, as long as merchants stayed away from unethical actions.

[82][83] By the late Ming dynasty, the officials often needed to solicit funds from powerful merchants to build new roads, schools, bridges, pagodas, or engage in essential industries, such as book-making, which aided the gentry class in education for the imperial examinations.

[84] Merchants began to imitate the highly cultivated nature and manners of scholar-officials in order to appear more cultured and gain higher prestige and acceptance by the scholarly elite.

[100] Ryukyuan students were also enrolled into the National Academy (Guozijian) in China, at Chinese government expense, and others studied privately at schools in Fujian province such diverse skills as law, agriculture, calendrical calculation, medicine, astronomy, and metallurgy.

[7][8][9] In the sixteenth century, lords began to centralise administration by replacing enfeoffment with stipend grants, and placing pressure on vassals to relocate into castle towns, away from independent power bases.

[104] In Silla Korea, the scholar-officials, also known as head rank 6, 5, and 4 (두품), were strictly hereditary castes under the bone-rank system (골품제도), and their power was limited by the royal clan who monopolized the positions of importance.

Head rank 6 leaders sojourned to China for study, while regional governance fell into the hojok or castle-lords commanding private armies detached from the central regime.

These factions coalesced, introducing a new national ideology that was an amalgamation of Chan Buddhism, Confucianism and Feng Shui, laying the foundation for the formation of the new Goryeo Kingdom.

[116] Chinese official positions, under various different native titles, go back to the courts of precolonial states of Southeast Asia, such as the Sultanates of Malacca and Banten, and the Kingdom of Siam.

[121] Overseas Chinese merchant families in British Malaya and the Dutch Indies donated generously to the provision of defence and disaster relief programs in China in order to receive nominations to the Imperial Court for honorary official ranks.

[124] Although appointed without state examinations, the Chinese officers emulated the scholar-officials of Imperial China, and were traditionally seen locally as upholders of the Confucian social order and peaceful coexistence under the Dutch colonial authorities.

[123] For much of its history, appointment to the Chinese officership was determined by family background, social standing and wealth, but in the twentieth century, attempts were made to elevate meritorious individuals to high rank in keeping with the colonial government's so-called Ethical Policy.

[123] The merchant and labour partnerships of China developed into the Kongsi Federations across Southeast Asia, which were associations of Chinese settlers governed through direct democracy.

These included soldiers and guards, religious clergy and diviners, eunuchs and concubines, entertainers and courtiers, domestic servants and slaves, prostitutes, and low class laborers other than farmers and artisans.

In an extreme example, the eunuch Wei Zhongxian (1568–1627) had his critics from the orthodox Confucian 'Donglin Society' tortured and killed while dominating the court of the Tianqi Emperor—Wei was dismissed by the next ruler and committed suicide.

[133] In popular culture texts such as Zhang Yingyu's The Book of Swindles (c. 1617), eunuchs were often portrayed in starkly negative terms as enriching themselves through excessive taxation and indulging in cannibalism and debauched sexual practices.

[143] Buddhist monkhood grew immensely popular from the fourth century, where the monastic life's exemption from tax proved alluring to poor farmers.

[145] However from the fourth to twentieth centuries, Buddhist monks were frequently sponsored by the elite of society, sometimes even by Confucian scholars, with monasteries described as "in size and magnificence no prince's house could match".

[148] Soldiers were not highly respected members of society,[48] specifically from the Song dynasty onward, due to the newly instituted policy of "Emphasizing the civil and downgrading the military" (Chinese: 重文輕武).

[149] Soldiers traditionally came from farming families, while some were simply debtors who fled their land (whether owned or rented) to escape lawsuits by creditors or imprisonment for failing to pay taxes.

However, in every instance, the policy would fail due to rampant desertion caused by the extremely low regard for violent occupations, and subsequently these armies had to be replaced with hired mercenaries or even peasant militia.

[157][158] Although the soldier was looked upon with a bit of disdain by scholar-officials and cultured people, military officers with successful careers could gain a considerable amount of prestige.