Fourier transform

The critical case for this principle is the Gaussian function, of substantial importance in probability theory and statistics as well as in the study of physical phenomena exhibiting normal distribution (e.g., diffusion).

Titchmarsh (1986) and Dym & McKean (1985) each gives three rigorous ways of extending the Fourier transform to square integrable functions using this procedure.

[26] As a consequence of this, it is possible to decompose L2(R) as a direct sum of four spaces H0, H1, H2, and H3 where the Fourier transform acts on Hek simply by multiplication by ik.

This fourfold periodicity of the Fourier transform is similar to a rotation of the plane by 90°, particularly as the two-fold iteration yields a reversal, and in fact this analogy can be made precise.

[37] If f is supported on the half-line t ≥ 0, then f is said to be "causal" because the impulse response function of a physically realisable filter must have this property, as no effect can precede its cause.

However, they do admit a Laplace domain description, with identical half-planes of convergence in the complex plane (or in the discrete case, the Z-plane), wherein their effects cancel.

In quantum mechanics, the momentum and position wave functions are Fourier transform pairs, up to a factor of the Planck constant.

Consider an increasing collection of measurable sets ER indexed by R ∈ (0,∞): such as balls of radius R centered at the origin, or cubes of side 2R.

[55] For an operator to be unitary it is sufficient to show that it is bijective and preserves the inner product, so in this case these follow from the Fourier inversion theorem combined with the fact that for any f, g ∈ L2(Rn) we have

Given an abelian locally compact Hausdorff topological group G, as before we consider space L1(G), defined using a Haar measure.

Taking the completion with respect to the largest possibly C*-norm gives its enveloping C*-algebra, called the group C*-algebra C*(G) of G. (Any C*-norm on L1(G) is bounded by the L1 norm, therefore their supremum exists.)

Given any abelian C*-algebra A, the Gelfand transform gives an isomorphism between A and C0(A^), where A^ is the multiplicative linear functionals, i.e. one-dimensional representations, on A with the weak-* topology.

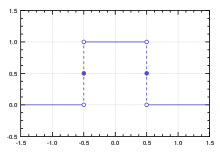

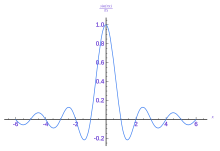

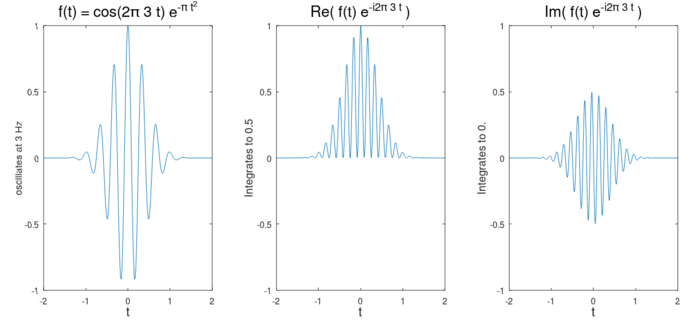

[28] The following figures provide a visual illustration of how the Fourier transform's integral measures whether a frequency is present in a particular function.

However, when you try to measure a frequency that is not present, both the real and imaginary component of the integral vary rapidly between positive and negative values.

The general situation is usually more complicated than this, but heuristically this is how the Fourier transform measures how much of an individual frequency is present in a function

Harmonic analysis is the systematic study of the relationship between the frequency and time domains, including the kinds of functions or operations that are "simpler" in one or the other, and has deep connections to many areas of modern mathematics.

But from the higher point of view, one does not pick elementary solutions, but rather considers the space of all distributions which are supported on the (degenerate) conic ξ2 − f2 = 0.

Then Fourier inversion gives, for the boundary conditions, something very similar to what we had more concretely above (put Φ(ξ, f) = ei2π(xξ+tf), which is clearly of polynomial growth):

Closed form formulas are rare, except when there is some geometric symmetry that can be exploited, and the numerical calculations are difficult because of the oscillatory nature of the integrals, which makes convergence slow and hard to estimate.

To begin with, the basic conceptual structure of quantum mechanics postulates the existence of pairs of complementary variables, connected by the Heisenberg uncertainty principle.

In classical mechanics, the physical state of a particle (existing in one dimension, for simplicity of exposition) would be given by assigning definite values to both p and q simultaneously.

In contrast, quantum mechanics chooses a polarisation of this space in the sense that it picks a subspace of one-half the dimension, for example, the q-axis alone, but instead of considering only points, takes the set of all complex-valued "wave functions" on this axis.

Nevertheless, choosing the p-axis is an equally valid polarisation, yielding a different representation of the set of possible physical states of the particle.

In non-relativistic quantum mechanics, Schrödinger's equation for a time-varying wave function in one-dimension, not subject to external forces, is

A simple example, in the absence of interactions with other particles or fields, is the free one-dimensional Klein–Gordon–Schrödinger–Fock equation, this time in dimensionless units,

Finally, the number operator of the quantum harmonic oscillator can be interpreted, for example via the Mehler kernel, as the generator of the Fourier transform

The power spectrum, as indicated by this density function P, measures the amount of variance contributed to the data by the frequency ξ.

The power spectrum ignores all phase relations, which is good enough for many purposes, but for video signals other types of spectral analysis must also be employed, still using the Fourier transform as a tool.

As discussed above, the characteristic function of a random variable is the same as the Fourier–Stieltjes transform of its distribution measure, but in this context it is typical to take a different convention for the constants.

Efficient procedures, depending on the frequency resolution needed, are described at Discrete-time Fourier transform § Sampling the DTFT.