Franco-Mongol alliance

Attempts to cement an alliance continued through negotiations with many leaders of the Mongol Ilkhanate in Persia, from its founder Hulagu through his descendants Abaqa, Arghun, Ghazan, and Öljaitü, but without success.

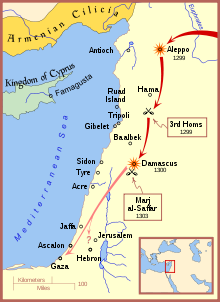

The Mongols invaded Syria several times between 1281 and 1312, sometimes in attempts at joint operations with the Franks, but the considerable logistical difficulties involved meant that forces would arrive months apart, never able to coordinate activities in any effective way.

[11] During the Fifth Crusade (1213–1221), as the Christians were unsuccessfully laying siege to the Egyptian city of Damietta, the legend of Prester John became conflated with the reality of Genghis Khan's rapidly expanding empire.

The northwestern Kipchak Khanate, known as the Golden Horde, expanded towards Europe, primarily via Hungary and Poland, while its leaders simultaneously opposed the rule of their cousins back at the Mongol capital.

[17] In the meantime, the Mongols' relentless march westward had displaced the Khawarizmi Turks, who themselves moved west, eventually allying with the Ayyubid Muslims in Egypt.

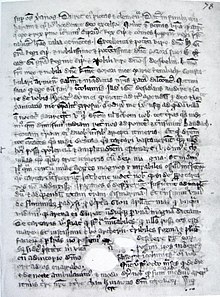

[4] In March 1245, Pope Innocent IV had issued multiple papal bulls, some of which were sent with an envoy, the Franciscan John of Plano Carpini, to the "Emperor of the Tartars".

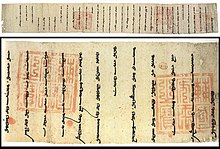

[21] However, the new Great Khan Güyük, who had been installed at Karakorum in 1246, replied only with a demand for the submission of the pope, and a visit from the rulers of the West in homage to Mongol power:[22] You should say with a sincere heart: "I will submit and serve you."

Warn your walls and your churches that soon our siege machinery will deal with them, your knights that soon our swords will invite themselves in their homes ... We will see then what use will be your alliance with Abagha.Bohemond was left with no estates except the County of Tripoli, which was itself to fall to the Mamluks in 1289.

Güyük's widow Oghul Qaimish simply gave the emissary a gift and a condescending letter to take back to King Louis, instructing him to continue sending tributes each year.

[55] The French historians Alain Demurger and Jean Richard suggest that this crusade may still have been an attempt at coordination with the Mongols, in that Louis may have attacked Tunis instead of Syria following a message from Abaqa that he would not be able to commit his forces in 1270, and asking to postpone the campaign to 1271.

[56][57] Envoys from the Byzantine emperor, the Armenians and the Mongols of Abaqa were present at Tunis, but events put a stop to plans for a continued crusade when Louis died of illness.

[4] In 1238, the European kings Louis IX of France and Edward I of England rejected the offer of the Nizari Imam Muhammad III of Alamut and the Abbasid caliph Al-Mustansir for a Muslim–Christian alliance against the Mongols.

[5] Despite their long history of enmity with the Mamluks, the Franks acknowledged that the Mongols were a greater threat, and after careful debate, chose to enter into a passive truce with their previous adversaries.

However, the French historian Jean Richard argues that Urban's act signaled a turning point in Mongol-European relations as early as 1263, after which the Mongols were considered as actual allies.

Though a Buddhist, upon his succession he married Maria Palaiologina, an Eastern Orthodox Christian and the illegitimate daughter of the Byzantine Emperor Michael VIII Palaiologos.

[94][95] The death of the Egyptian leader Baibars in 1277 led to disorganization in the Muslim territories, making conditions ripe for a new action by other factions in the Holy Land.

[94] In September 1281 the Mongols returned, with 19,000 of their own troops, plus 20,000 others including Armenians under Leo III, Georgians, and 200 Knights Hospitaller from Marqab, who sent a contingent even though the Franks of Acre had agreed a truce with the Mamluks.

[102][103] Kelemechi met with Pope Honorius IV in 1285, offering to "remove" the Saracens (Muslims) and divide "the land of Sham, namely Egypt" with the Franks.

[105][106][107] Bar Sauma was greeted warmly by the European monarchs,[100] but Western Europe was no longer as interested in the Crusades, and the mission to form an alliance was ultimately fruitless.

Stability was restored when Arghun's son Ghazan took power in 1295, though to secure cooperation from other influential Mongols, he made a public conversion to Islam when he took the throne, marking a major turning point in the state religion of the Ilkhanate.

Despite being an official Muslim, however, Ghazan remained tolerant of multiple religions, and worked to maintain good relations with his Christian vassal states such as Cilician Armenia and Georgia.

[119][120][121] The ships left Famagusta on July 20, 1300, to raid the coasts of Egypt and Syria: Rosette, Alexandria, Acre, Tortosa, and Maraclea, before returning to Cyprus.

[129] A few marital alliances between Christian rulers and the Mongols of the Golden Horde continued, such as when the Byzantine emperor Andronicus II gave daughters in marriage to Toqta (d. 1312) and later to his successor Özbeg (1312–1341).

Abu Sa'id died in 1335 with neither heir nor successor, and the Ilkhanate lost its status after his death, becoming a plethora of little kingdoms run by Mongols, Turks, and Persians.

[132] In the early 15th century, Timur resumed relations with Europe, attempting to form an alliance against the Egyptian Mamluks and the Ottoman Empire, and engaged in communications with Charles VI of France and Henry III of Castile, but died in 1405.

[13][133][134][135][136] In the cultural sphere, there were some Mongol elements in Western medieval art, especially in Italy, of which most surviving examples are from the 14th century, after the chance of a military alliance had faded.

"[89] Timothy May described the alliance as having its peak at the Council of Lyon in 1274,[144] but that it began to unravel in 1275 with the death of Bohemond, and May too admitted that the forces never engaged in joint operations.

[8] The 20th-century historian Glenn Burger said, "The refusal of the Latin Christian states in the area to follow Hethum's example and adapt to changing conditions by allying themselves with the new Mongol empire must stand as one of the saddest of the many failures of Outremer.

Monarchs in Western Europe often vocally entertained the idea of going on crusade as a way of making an emotional appeal to their subjects, but would ultimately take years to prepare, sometimes never actually left for Outremer.

Even the Armenian historian Hayton of Corycus, the most enthusiastic advocate of Western-Mongol collaboration, freely admitted that the Mongol leadership was not inclined to listen to European advice.