Franconian War

Today's historians use the term mainly because it conveys the sense that two opponents with conflicting interests were involved in the fighting and the situation was more complex than one might think, if it were simply seen as a retaliation against the robber barons.

For the Franconian Imperial Knights, whose importance was waning, it was also a means to combat the power of the emerging territorial states, such as the Bishopric of Bamberg and Burgraviate of Nuremberg, as well their margraviates, Kulmbach and Ansbach.

However, the robber barons often misused this means of dispute, because a feud had inter alia to be properly announced and needed a reasonable justification.

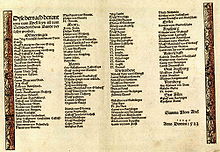

According to Roth von Schreckenstein,[1] members of the Swabian League included the following Bavarian, Franconian and Swabian noble families: Seckendorff, Stain, Reischach, Wellwart, Schwendi, Echter, Torringer, Seibolstorff, Nothaft, Preysing, Nußberg, Hundt, Freiberg, Auer, Löffelholz, Ehingen, Hürnheim, Sotzingen, Thumb, Gültlingen, Rieringen, Ow zu Wachendorf, and Knöringen.

Noble families who had successfully dealt with this structural change usually presented themselves for service to territorial princes or the Emperor and were given important posts such as Hofmeister or Amtmann.

Nevertheless, Hans Thomas Absberg had strong backing among the Franconian knights; his closest followers came from prominent families, like the Rosenbergs, Thüngens, Guttenbergs, Wirsbergs, Sparnecks, and Aufseßes.

Besides In addition to imperially free estates, the borders of the bishoprics of Bamberg and Würzburg, Brandenburg-Kulmbach and the road to Bohemia and Saxony all lay close together.

At the end of the campaign, some families were able to reconcile with the Swabian League and their estates were restored in return for a sum of gold and the promise that they would respect the peace.