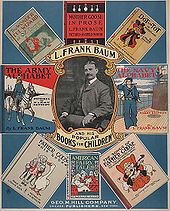

L. Frank Baum

From the age of 12, he spent two years at Peekskill Military Academy, but after being severely disciplined for daydreaming, he had a possibly psychogenic heart attack and was allowed to return home.

He had always been close to his younger brother Henry (Harry) Clay Baum, who helped in the production of The Rose Lawn Home Journal.

His skyrockets, Roman candles, and fireworks filled the sky, while many people around the neighborhood would gather in front of the house to watch the displays.

She was the founder of Syracuse Oratory School, and Baum advertised his services in her catalog to teach theater, including stage business, play writing, directing, translating (French, German, and Italian), revision, and operettas.

His habit of giving out wares on credit led to the eventual bankrupting of the store,[16] so Baum turned to editing the local newspaper The Aberdeen Saturday Pioneer where he wrote the column Our Landlady.

[17] Following the death of Sitting Bull at the hands of Indian agency police, Baum recommended the wholesale extermination of all America's native peoples in a column that he wrote on December 20, 1890 (full text below).

[18] It is unclear whether Baum meant it as a satire or not, especially since his mother-in-law Matilda Joslyn Gage received an honorary adoption into the Wolf Clan of the Mohawk Nation and was a fierce defender of Native American rights,[19] but on January 3, 1891, he returned to the subject in an editorial response to the Wounded Knee Massacre:[20] The Pioneer has before declared that our only safety depends upon the total extirmination [sic] of the Indians.

Two years after Wizard's publication, Baum and Denslow teamed up with composer Paul Tietjens and director Julian Mitchell to produce a musical stage version of the book under Fred R.

The stage version starred Anna Laughlin as Dorothy Gale, alongside David C. Montgomery and Fred Stone as the Tin Woodman and Scarecrow respectively, which shot the pair to instant fame.

Toto was replaced with Imogene the Cow, and Tryxie Tryfle (a waitress) and Pastoria (a streetcar operator) were added as fellow cyclone victims.

The Wicked Witch of the West was eliminated entirely in the script, and the plot became about how the four friends were allied with the usurping Wizard and were hunted as traitors to Pastoria II, the rightful King of Oz.

Jokes in the script, mostly written by Glen MacDonough, called for explicit references to President Theodore Roosevelt, Senator Mark Hanna, Rev.

Even so, his other works remained very popular after his death, with The Master Key appearing on St. Nicholas Magazine's survey of readers' favorite books well into the 1920s.

[32][33] Nevertheless, Baum stated to the press that he had discovered a Pedloe Island off the coast of California and that he had purchased it to be "the Marvelous Land of Oz," intending it to be "a fairy paradise for children."

He did not get back to a stable financial situation for several years, after he sold the royalty rights to many of his earlier works, including The Wonderful Wizard of Oz.

Donahue Company publishing cheap editions of his early works with advertising which purported that Baum's newer output was inferior to the less expensive books that they were releasing.

[36] However, Baum had shrewdly transferred most of his property into Maud's name, except for his clothing, his typewriter, and his library (mostly of children's books, such as the fairy tales of Andrew Lang, whose portrait he kept in his study)—all of which, he successfully argued, were essential to his occupation.

He continued theatrical work with Harry Marston Haldeman's men's social group The Uplifters,[37] for which he wrote several plays for various celebrations.

The films were directed by J. Farrell MacDonald, with casts that included Violet MacMillan, Vivian Reed, Mildred Harris, Juanita Hansen, Pierre Couderc, Mai Welles, Louise Emmons, J. Charles Haydon, and early appearances by Harold Lloyd and Hal Roach.

Nancy Tystad Koupal notes an apparent loss of interest in editorializing after Aberdeen failed to pass the bill for women's enfranchisement.

In this story, General Jinjur leads the girls and women of Oz in a revolt, armed with knitting needles; they succeed and make the men do the household chores.

[49][50] The piece opined that with Sitting Bull's death, "the nobility of the Redskin" had been extinguished, and the safety of the frontier would not be established until there was "total annihilation" of the remaining Native Americans, who, he claimed, lived as "miserable wretches."

Baum mentions his characters' distaste for a Hopi snake dance in Aunt Jane's Nieces and Uncle John, but he also deplores the horrible situation which exists on Native American reservations.

[citation needed] Baum's mother-in-law and woman's suffrage leader Matilda Joslyn Gage strongly influenced his views.

Gage was initiated into the Wolf Clan and admitted into the Iroquois Council of Matrons in recognition of her outspoken respect and sympathy for the Native American people.

Henry Littlefield, an upstate New York high school history teacher, wrote a scholarly article in 1964, the first full-fledged interpretation of the novel as an extended metaphor of the politics and characters of the 1890s.

[56] Since 1964, many scholars, economists, and historians have expanded on Littlefield's interpretation, pointing to multiple similarities between the characters (especially as depicted in Denslow's illustrations) and stock figures from editorial cartoons of the period.

Littlefield wrote to The New York Times letters to the editor section spelling out that his theory had no basis in fact, but that his original point was "not to label Baum, or to lessen any of his magic, but rather, as a history teacher at Mount Vernon High School, to invest turn-of-the-century America with the imagery and wonder I have always found in his stories.

[60][61] Writers including Evan I. Schwartz[62] among others have suggested that Baum intentionally used allegory and symbolism in The Wonderful Wizard of Oz to convey concepts that are central to spiritual teachings such as Theosophy and Buddhism.

The article cites various symbols and their possible meanings, for example the Yellow Brick Road representing the 'Golden Path' in Buddhism, along which the soul travels to a state of spiritual realization.