Frank Rosenblatt

[2] Also in 1966, he became fascinated with the transfer of learned behavior from trained to naive rats by the injection of brain extracts, a subject on which he would publish extensively in later years.

The New York Times billed it as a revolution, with the headline "New Navy Device Learns By Doing",[9] and The New Yorker similarly admired the technological advancement.

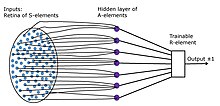

The first theorem states that elementary perceptrons can solve any classification problem if there are no discrepancies in the training set (and sufficiently many independent A-elements).

Minsky and Papert considered elementary perceptrons with restrictions on the neural inputs: a bounded number of connections or a relatively small diameter of A-units receptive fields.

These results are not contradictory, but the Minsky and Papert book was widely (and wrongly) cited as the proof of strong limitations of perceptrons.

(For detailed elementary discussion of the first Rosenblatt's theorem and its relation to Minsky and Papert work we refer to a recent note.

This new wave of study on neural networks is interpreted by some researchers as being a contradiction of hypotheses presented in the book Perceptrons, and a confirmation of Rosenblatt's expectations.

Rosenblatt used the book to teach an interdisciplinary course entitled "Theory of Brain Mechanisms" that drew students from Cornell's Engineering and Liberal Arts colleges.

[13] Rosenblatt spent his last several years on this problem and showed convincingly that the initial reports of larger effects were wrong and that any memory transfer was at most very small.

[3] He also studied photometry and developed a technique for "detecting low-level laser signals against a relatively intense background of non-coherent light".

He worked in the Eugene McCarthy primary campaigns for president in New Hampshire and California in 1968 and in a series of Vietnam protest activities in Washington.