Frank Rutter

[6] In 1910, he began to actively support women's suffrage, chairing meetings, and giving sanctuary to suffragettes released from prison under the Cat and Mouse Act—helping some to leave the country.

[2][16] Whilst still at school, Rutter, along with a fellow sixth form student, Edgar D., explored London nightlife, visiting music halls, eating out in Gatti's Restaurant and joining nightclubs, which were then an adjunct to the more formal London's gentleman's club, providing a dining room, ballroom, writing room, and female membership, which was not taken up by respectable women in society, although the male membership was mostly respectable; Rutter's father happily financed these activities.

[15] When at Cambridge, Rutter gained popularity through his banjo-playing,[2] and, thanks to the good train service available, extended his social pursuits to Paris, first visiting in 1898, speaking French fluently and often staying for a month at a time in the city,[15] where he made friends in the Latin Quarter.

[4][18] He considered "perfectly dreadful"[19] the lack of such work in the national collections, pointing out in 1905 that the only example of the modern French school was Edgar Degas' The Ballet from Robert the Devil (1876) in the Victoria and Albert Museum.

[19] Sargent and Wertheimer each sent ten guineas; Blanche Marchesi staged a fund-raising concert; Rutter, although "extremely nervous" gave his first lecture at the Grafton Galleries.

[19] Rutter's choice was Monet's Vétheuil: Sunshine and Snow (since retitled Lavacourt under Snow), which MacColl was in favour of and Durand-Ruel had promised to sell for the amount collected, but Phillips pointed out that National Gallery did not accept work by living artists; discreet enquiries revealed that the gallery trustees also found too "advanced" Manet, Sisley and Pissarro: "They were certainly dead—but they had not been dead long enough for England", wrote Rutter, adding "I nearly wept with disappointment.

"[19] To avoid any accusations of logrolling Durand-Ruel's exhibition, they agreed that Rutter would travel to Van der Veldt, a private collector in Le Havre, to choose a Boudin painting.

[14] From October 1909 to 1912,[1] Rutter also published and edited the weekly, cheaply printed Art News (sold for 2d a week), the journal of the AAA, like which it had an open-door policy on contributors, featuring the lectures given to the Royal Academy Schools by Sir William Blake Richmond, as well as Sickert's attack on the Royal Academy, "Straws from Cumberland Market",[6] his column on topical issues being the main attraction.

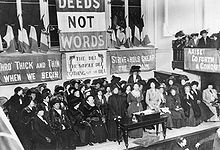

[14] On 12 January 1910, at the Eustace Miles Restaurant, Rutter chaired the meeting of a group which developed into the Men’s Political Union for Women’s Enfranchisement,[7] of which he was the honorary treasurer.

[7] In 1910, Roger Fry occupied the limelight of avant-garde campaigning for art, when he outraged the public with an exhibition Manet and the post-impressionists at the Grafton Galleries, showcasing work by Van Gogh, Gauguin and Cézanne.

[28] In April 1912, because of financial difficulties,[14] Rutter resigned as secretary of the AAA, which had been strongly supported by Lucien Pissarro, Walter Sickert and others, but which he felt was nevertheless dwindling away due to what he condemned as "the incurable snobbishness of the English artist".

[14] He used his house at 7 Westfield Terrace, Chapel Allerton, Leeds, to provide accommodation for suffragettes released from prison under the Cat and Mouse Act and recovering from hunger strike.

[7] In 1913, he provided a character reference so that a job could be obtained in Europe by a "mouse", Elsie Duval; another, Lilian Lenton, a suffragette arsonist also escaped via his home to France in June that year with the aid of his wife.

[7][14] Elizabeth Crawford, author of The Women's Suffrage Movement, suggests that other similar events must have taken place, but were kept quiet at the time out of necessity and, later, due to Rutter's taciturnity.

[29] Rutter initially had plans to create a modern art collection at the Leeds gallery, but had been frustrated in this aim by "boorish" local councillors; his association with the escape of Lilian Lenton had further damaged his standing.

[14] In October 1913, Rutter was commissioned by the Doré Gallery at 35 Bond Street in the West End to curate the Post-Impressionist and Futurist Exhibition, which displayed the story of those movements from Camille Pissarro to Vorticist Wyndham Lewis (who was no longer on good terms with Fry).

[31] Rutter made a link between the British artists he supported and the French intimiste painters, as well as featuring artworks by Severini and Boccioni of the Italian Futurism movement—which had been shown in London first by the Sackville Gallery—and by Brâncuși, Epstein, Delaunay and Signac.

[36] Underneath an 1894 woodcut by Lucien Pissarro, page one carried an editorial explaining the delayed publication due to the outbreak of war and justifying the use of scarce materials, compared to other periodicals "which give vulgar and illiterate expression to the most vile and debasing sentiments.

"[38] It was also stated that some of the contributors were serving at the front and that educated men in the army were keen to see such a publication: "Engaged, as their duty bids, on harrowing work of destruction, they exhort their elders at home never to lose sight of the supreme importance of creative art.

"[41] On 28 March 1920 in The Sunday Times, Rutter reviewed the short-lived Group X (a reforming of the Vorticists), "the real tendency of the exhibition is towards a new sort of realism, evolved by artists who have passed through a phase of abstract experiment.".

[43] He suffered from a bronchial complaint for a number of years, as a result of which he periodically sojourned on the South Coast, visiting London exhibitions when he felt in good enough health to do so.