Frankfurt National Assembly

The unrest that resulted from the 1830 French July Revolution led to a temporary reversal of that trend, but after the demonstration for civic rights and national unity at the 1832 Hambach Festival, and the abortive attempt at an armed rising in the 1833 Frankfurter Wachensturm, the pressure on representatives of constitutional or democratic ideas was raised through measures such as censorship and bans on public assemblies.

The 1840s began with the Rhine Crisis, a primarily diplomatic scandal caused by the threat from the French prime minister Adolphe Thiers to invade Germany in a dispute between Paris and the four other Great Powers (including Austria and Prussia) over the Middle East.

The boycott in Austria's Czech majority areas and complications in Tiengen (Baden), (where the leader of the Heckerzug rebellion, Freidrich Hecker, in exile in Switzerland, was elected in two rounds) caused disruptions.

Six sections with 49 paragraphs regulated the electoral test, the board and staff of the assembly, quorum (set at 200 deputies), the formation of committees, order of debate, and inputs and petitions.

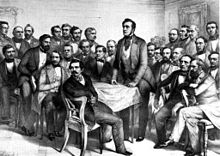

[18] Due to their oppositional views, many of them had already conflicted with their princes for several years, including professors such as Jacob Grimm, Friedrich Christoph Dahlmann, Georg Gottfried Gervinus and Wilhelm Eduard Albrecht (all counted among the Göttingen Seven), and politicians such as Welcker and Itzstein who had been champions of constitutional rights for two decades.

Among the professors, besides lawyers, experts in German Studies and historians were especially common, because under the sway of restoration politics, academic meetings in such disciplines, e.g. the Germanisten-Tage of 1846 and 1847, were often the only occasions where national themes could be discussed freely.

Apart from those mentioned above, the academic Ernst Moritz Arndt, Johann Gustav Droysen, Carl Jaup, Friedrich Theodor Vischer, Bruno Hildebrand and Georg Waitz are especially notable.

The Archduke received the delegation on 5 July 1848 and accepted the position, stating, however, that he could not undertake full responsibility in Frankfurt until he had finished his current work of opening the Austrian Parliament in Vienna.

When King Frederick VII announced on 27 March 1848 the promulgation of a liberal constitution under which the duchy, while preserving its local autonomy, would become an integral part of Denmark, the radicals broke into revolt.

With Prussia threatened by war on several fronts, terms for an armistice were arranged through Swedish mediation at Malmö on 2 July 1848 and the order to cease operations handed to General Wrangel ten days later.

They tried to steer a middle course by recognizing Wrangel's actions but asked the Regent for direct control of the German Federal Army in order to enforce a peace based on 2 July agreement.

This early divide of its main components was of major importance for the later failure of the National Assembly, as it caused lasting damage not only to the esteem and acceptance of the parliament, but also to the cooperation among its factions.

National enthusiasm led to numerous penny-collections across Germany, as well the raising of volunteers to man whatever vessels could be purchased, to be commanded by retired naval officers from coastal German states.

Difficulties arose in the procurement and equipment of suitable warships, as the British and Dutch were wary of a new naval power arising in the North Sea, and Denmark pressed its blockade harder.

Discussions in the National Assembly for raising funds through taxes were tied into the Constitutional debates, and the Provisional Central Power could not convince the state governments to make any more contributions than what they had agreed upon in the Confederate Diet.

Even worse, the chaotic finances of such states as Austria, which was fighting wars in Italy and Hungary and suppressing rebellions in Prague and Vienna, meant little or no payment was to be expected in the near future.

Effectively, the National Assembly and the Provisional Central Power were bankrupt and unable to undertake such rudimentary projects as paying salaries, purchasing buildings, or even publishing notices.

On 20 July the Regent, along with Heinrich Gagern and a large deputation from the Parliament, accepted an invitation by King Frederick William to take part in a festival celebrating new construction to the great Cologne Cathedral.

In Revolution and Counter-Revolution in Germany (1852), Friedrich Engels wrote: The fact that fate of the revolution was decided in Vienna and Berlin, that the key issues of life were dealt with in both those capitals without taking the slightest notice of the Frankfurt assembly—that fact alone is sufficient to prove that the institution was a mere debating club, consisting of an accumulation of gullible wretches who allowed themselves to be abused as puppets by the governments, so as to provide a show to amuse the shopkeepers and tradesmen of small states and towns, as long as it was considered necessary to distract their attention.

Similar to Bohemia, the National Assembly was determined to incorporate much of the Prussian Grand Duchy of Posen against the wishes of the majority Polish population, especially after the failed Greater Poland uprising which lasted from 20 March until 9 May.

The "Smaller German Solution" (Kleindeutsche Lösung) aimed for a Germany under the leadership of Prussia and excluded Imperial Austria so as to avoid becoming embroiled in the problems of that multi-cultural state.

The majority of the radical left voted for the Greater German variant, accepting the possibility formulated by Carl Vogt of a "holy war for western culture against the barbarism of the East",[43] i.e., against Poland and Hungary, whereas the liberal centre supported a more pragmatic stance.

A list of amendments were proposed by 29 governments in common and on 15 February Gottfried Ludolf Camphausen, Prussia's representative to the National Assembly, handed the draft to Prime Minister Gagern, who forwarded it to the Committee of the Parliament that was preparing the Constitution for its second reading.

As the near-inevitable result of having chosen the Smaller German Solution and the constitutional monarchy as form of government, the Prussian king was elected as hereditary head of state on 28 March 1849.

The deputies knew that Frederick William IV held strong prejudices against the work of the Frankfurt Parliament, but on 23 January, the Prussian government had informed the states of the German Confederation that Prussia would accept the idea of a hereditary emperor.

Therefore, Prussia chose to support the Unionspolitik ("union policy") designed by the conservative Paulskirche deputy Joseph von Radowitz for a Smaller German Solution under Prussian leadership.

With this in mind, Archduke John attempted to resign his office once more in August 1849, stating that the Regency should be jointly held by Prussia and Austria through a committee of four until 1 May 1850, by which time all of the German governments should have decided on a new Constitution.

Prussia's role as a Great Power in Europe did not recover until the Crimean War saw Russia isolated, Austria maligned for its wavering policy, and Britain and France embarrassed by their poor military performance.

[60] Prussia had also won the gratitude of the family of the Grand Duchy of Baden as an important ally in southern Germany, and the Smaller German Solution gained in popularity throughout the nation.

Historians have suggested several possible explanations for the German Sonderweg of the 20th century: discreditation of democrats and liberals, their estrangement, and the unfulfilled desire for a nation-state, which had led to separation of the national question from the assertion of civic rights.