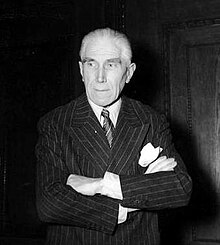

Franz von Papen

Born into a wealthy, powerful and famous family of Westphalian Catholic aristocrats, Papen served in the Prussian Army from 1898 onward and was trained as a German General Staff officer.

At one time, when the anti-Huerta Zapatistas were advancing on Mexico City, Papen organised a group of European volunteers to fight for Mexican General Victoriano Huerta.

[7] During his time in Mexico, Papen acquired the love of international intrigue and adventure that characterised his later diplomatic postings in the United States, Austria and Turkey.

[10] Papen, who was given an unlimited fund of cash to draw on by Berlin, attempted to block the British, French and Russian governments from buying war supplies in the United States.

[9] Papen set up a front company that tried to preclusively purchase every hydraulic press in the US for the next two years to limit artillery shell production by US firms with contracts with the Allies.

[11] In October 1914, Papen became involved with what was later dubbed "the Hindu–German Conspiracy", by covertly arranging with Indian nationalists based in California for arms trafficking to the latter for a planned uprising against the British Raj.

In February 1916, he contacted Mexican Colonel Gonzalo Enrile, living in Cuba, in an attempt to arrange German support for Félix Díaz, the would-be strongman of Mexico.

[18] Papen served as an intermediary between Roger Casement of the Irish Volunteers and German naval intelligence for the purchase and delivery of arms to be used in Dublin during the Easter Rising of 1916.

After the Turks signed an armistice with the Allies on 30 October 1918, the German Asia Corps was ordered home, and Papen was in the mountains at Karapinar when he heard on 11 November 1918 that the war was over.

Papen, along with two of his future cabinet ministers, was a member of Arthur Moeller van den Bruck's exclusive Berlin Deutscher Herrenklub (German Gentlemen's Club).

[39] But with chancellor Heinrich Brüning's presidential government's dependence upon the Social Democrats in the Reichstag to "tolerate" it by not voting to cancel laws passed under Article 48, Papen grew more critical.

Schleicher selected Papen because his conservative, aristocratic background and military career made him acceptable to Hindenburg and would create the groundwork for a possible coalition between the Centre Party and the Nazis.

[71] In November 1932, Papen violated the terms of the Treaty of Versailles by approving a program of refurbishment for the German Navy of an aircraft carrier, six battleships, six cruisers, six destroyer flotillas, and 16 submarines, intended to allow Germany to control both the North Sea and the Baltic.

[73] However, at a cabinet meeting on 2 December, Papen was informed by Schleicher's associate General Eugen Ott about the dubious results of Reichswehr war games, that showed there was no way to maintain order against the Nazis and Communists.

[38] On 4 January 1933, Hitler and Papen met in secret at the banker Kurt Baron von Schröder's house in Cologne to discuss a common strategy against Schleicher.

"[87][88] Editor-in-Chief Theodor Wolff commented in an editorial in the Berliner Tagblatt on January 29, 1933: "The strongest natures, those with the iron forehead or the board before the head, will insist on the anti-parliamentary solution, on the closing of the Reichstag House, on the coup d'état.

For example, as part of the deal between Hitler and Papen, Göring had been appointed interior minister of Prussia, thus putting the largest police force in Germany under Nazi control.

On 1 February 1933, Hitler presented to the cabinet an Article 48 decree law that had been drafted by Papen in November 1932 allowing the police to take people into "protective custody" without charges.

[94] On 18 March 1933, in his capacity as Reich Commissioner for Prussia, Papen freed the "Potempa Five" under the grounds the murder of Konrad Pietzuch was an act of self-defense, making the five SA men "innocent victims" of a miscarriage of justice.

After the Enabling Act was passed, serious deliberations more or less ceased at cabinet meetings when they took place at all, which subsequently neutralised Papen's attempt to "box" Hitler in through cabinet-based decision-making.

During his stay in Rome, Papen met the Italian Prime Minister Benito Mussolini and failed to persuade him to drop his support for the Austrian chancellor Dollfuss.

Instead, in the Night of the Long Knives, the Vice-Chancellery, Papen's office, was ransacked by the Schutzstaffel (SS); his associates Herbert von Bose, Erich Klausener and Edgar Julius Jung were shot.

[118] Papen was a German nationalist who always believed that Austria was destined to join Germany in an Anschluss (annexation), and felt that a success in bringing that about might restore his career.

[127] In July 1936, Papen reported to Hitler that the Austro-German treaty he had just signed was the "decisive step" towards ending Austrian independence, and it was only a matter of time before the Anschluss took place.

[132] The ultimatum that Hitler presented to Schuschnigg at the meeting on 12 February 1938 led to the Austrian government's capitulation to German threats and pressure, and paved the way for the Anschluss that year.

[133] In November 1938 and in February 1939, the new Turkish president General İsmet İnönü again vetoed Ribbentrop's attempts to have Papen appointed as German ambassador to Turkey.

[148] Papen claimed after the war to have done everything within his power to save Turkish Jews living in countries occupied by Germany from deportation to the death camps, but an examination of the Auswärtige Amt's records does not support him.

The German government considered appointing Papen ambassador to the Holy See, but Pope Pius XII, after consulting Konrad von Preysing, Bishop of Berlin, rejected this proposal.

Papen praised the Schuman Plan to pacify relations between France and West Germany as "wise and statesmanlike" and claimed to believe in the economic and military unification and integration of Western Europe.

Right up until his death in 1969, Papen gave speeches and wrote articles in the newspapers, defending himself against the charge that he had played a crucial role in having Hitler appointed chancellor and that he had served a criminal regime; these led to vitriolic exchanges with West German historians, journalists and political scientists.