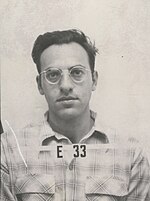

Frederick Reines

"[2] A graduate of Stevens Institute of Technology and New York University, Reines joined the Manhattan Project's Los Alamos Laboratory in 1944, working in the Theoretical Division in Richard Feynman's group.

In the early 1950s, working in Hanford and Savannah River Sites, Reines and Cowan developed the equipment and procedures with which they first detected the supposedly undetectable neutrinos in June 1956.

For a time he considered the possibility of a singing career, and was instructed by a vocal coach from the Metropolitan Opera who provided lessons for free because the family did not have the money for them.

He later recalled that: The first stirrings of interest in science that I remember occurred during a moment of boredom at religious school, when, looking out of the window at twilight through a hand curled to simulate a telescope, I noticed something peculiar about the light; it was the phenomenon of diffraction.

[4]Ironically, Reines excelled in literary and history courses, but received average or low marks in science and math in his freshman year of high school, though he improved in those areas by his junior and senior years through the encouragement of a teacher who gave him a key to the school laboratory.

He studied cosmic rays there under Serge A. Korff,[4] but wrote his thesis under the supervision of Richard D. Present[3] on "Nuclear fission and the liquid drop model of the nucleus".

[3][7] In 1944 Richard Feynman recruited Reines to work in the Theoretical Division at the Manhattan Project's Los Alamos Laboratory, where he would remain for the next fifteen years.

At the conclusion of the Greenhouse test series, Reines had received permission from the head of T Division, J. Carson Mark, for a leave in residence to study fundamental physics.

They then realised that by adding cadmium salt to their liquid scintillator they would enhance the neutron capture reaction, resulting in a burst of gamma rays with a total energy of 9 MeV.

The detector was proposed to be dropped at the moment of explosion into a hole 40 meters from the detonation site "to catch the flux at its maximum"; it was named "El Monstro".

With encouragement from John A. Wheeler, they tried again in 1955, this time using one of the newer, larger 700 MW reactors at the Savannah River Site that emitted a high neutrino flux of 1.2 x 1012 / cm2 sec.

[3] On the basis of his work in first detecting the neutrino, Reines became the head of the physics department of Case Western Reserve University from 1959 to 1966.

Reines brought his friends, an engineer August "Gus" Hruschka from the US,[19] they worked together with South African physicist Friedel Sellschop of the University of Witwatersrand.

The decision to work in an apartheid racist country was challenged by many colleagues of Reines, he himself said that "science transcended politics".

[15] The laboratory team in the mine was led by Reines' graduate students, first by William Kropp, and then by Henry Sobel.

[3] In 1966, Reines took most of his neutrino research team with him when he left for the new University of California, Irvine (UCI), becoming its first dean of physical sciences.

Supernova explosions are rare, but Reines thought he might be lucky enough to see one in his lifetime, and be able to catch the neutrinos streaming from it in his specially-designed detectors.

[18] In 1987, neutrinos emitted from Supernova SN1987A were detected by the Irvine–Michigan–Brookhaven (IMB) Collaboration, which used an 8,000 ton Cherenkov detector located in a salt mine near Cleveland.

[2] In 1995 Reines was honored, along with Martin L. Perl, with the Nobel Prize in Physics for his work with Cowan in first detecting the neutrino.

[22] Frederick Reines Hall, which houses the Physics and Astronomy Department at the University of California, Irvine, was named in his honor.