History of central banking in the United States

Russell Lee Norburn said the fundamental cause of the American Revolutionary War was conservative Bank of England policies failing to supply the colonies with money.

Robert Morris, as Superintendent of Finance, helped to open the Bank of North America in 1782, and has been accordingly called by Thomas Goddard "the father of the system of credit and paper circulation in the United States".

However, it was thwarted in fulfilling its intended role as a nationwide national bank due to objections of "alarming foreign influence and fictitious credit",[2] favoritism to foreigners and unfair policies against less corrupt state banks issuing their own notes, such that Pennsylvania's legislature repealed its charter to operate within the Commonwealth in 1785.

In 1791, former Morris aide and chief advocate for Northern mercantile interests, Alexander Hamilton, the Secretary of the Treasury, accepted a compromise with the Southern lawmakers to ensure the continuation of Morris's Bank project; in exchange for support by the South for a national bank, Hamilton agreed to ensure sufficient support to have the national or federal capitol moved from its temporary Northern location, New York, to a "Southern" location on the Potomac.

James Madison signed the charter with the intention of stopping runaway inflation that had plagued the country during the five-year interim.

Jackson attempted to counteract this by executive order requiring all federal land payments to be made in gold or silver, in accordance with his interpretation of The Constitution of the United States, which only gives Congress the power to "coin" money, not emit bills of credit.

The bank then flatly denied a subpoena to examine its records and its chief, Nicholas Biddle, bemusedly observed that it would be ironic if he went to prison "By the votes of members of Congress because I would not give up to their enemies their confidential letters".

They could issue bank notes against specie (gold and silver coins) and the states heavily regulated their own reserve requirements, interest rates for loans and deposits, the necessary capital ratio etc.

The Michigan Act (1837) allowed the automatic chartering of banks that would fulfill its requirements without special consent of the state legislature.

[14] Congress suspended the gold standard in 1861 early in the Civil War and began issuing paper currency (greenbacks).

The federally issued greenbacks were gradually supposed to be eliminated in favor of national bank notes after the Specie Payment Resumption Act of 1875 was passed.

Early in 1907, Jacob Schiff, the chief executive officer of Kuhn, Loeb and Co., in a speech to the New York Chamber of Commerce, warned that "unless we have a central bank with adequate control of credit resources, this country is going to undergo the most severe and far reaching money panic in its history.

[Herrick] Bankers felt the real problem was that the United States was the last major country without a central bank, which might provide stability and emergency credit in times of financial crisis.

Financial leaders who advocated a central bank with an elastic currency after the Panic of 1907 included Frank Vanderlip, Myron T. Herrick, William Barret Ridgely, George E. Roberts, Isaac Newton Seligman and Jacob H. Schiff.

They went to Europe and were impressed with how the central banks in Britain and Germany appeared to handle the stabilization of the overall economy and the promotion of international trade.

Aldrich's investigation led to his plan in 1912 to bring central banking to the United States, with promises of financial stability, expanded international roles, control by impartial experts and no political meddling in finance.

William Jennings Bryan, now Secretary of State, long-time enemy of Wall Street and still a power in the Democratic Party, threatened to destroy the bill.

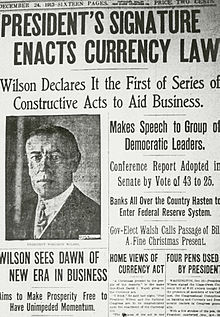

Wilson assured southerners and westerners that the system was decentralized into 12 districts, and thus would weaken New York City's Wall Street influence and strengthen the hinterlands.

The Federal Reserve's monetary powers did not dramatically change for the rest of the 20th century, but in the 1970s it was specifically charged by Congress to effectively promote "the goals of maximum employment, stable prices, and moderate long-term interest rates" as well as given regulatory responsibility over many consumer credit protection laws.