Freedmen's Bureau

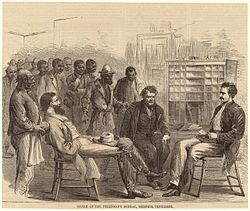

It was established on March 3, 1865, and operated briefly as a federal agency after the War, from 1865 to November 1872, to direct provisions, clothing, and fuel for the immediate and temporary shelter and supply of destitute and suffering refugees and freedmen and their wives and children.

[7] Bureau agents also served as legal advocates for African Americans in both state and federal courts, mostly in cases dealing with family issues.

It kept an eye on the contracts between the newly free laborers and planters, given that few freedmen had yet gained adequate reading skills, and pushed whites and blacks to work together in a free-labor market as employers and employees rather than as masters and slaves.

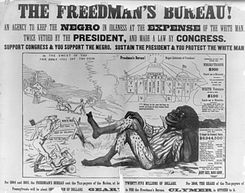

President Andrew Johnson, a Southern Democrat who had succeeded to the office following Lincoln's assassination[8] in 1865, vetoed the bill, arguing that the Bureau encroached on states' rights, relied inappropriately on the military in peacetime, gave blacks help that poor whites had never had, and would ultimately prevent freed slaves from becoming self-sufficient by rendering them dependent on public assistance.

[5][9] Though the 39th United States Congress—controlled by Radical Republicans—overrode Johnson's veto, by 1869 Southern Democrats in Congress had deprived the Bureau of most of its funding, and as a result it had to cut much of its staff.

[12] The Bureau mission was to help solve everyday problems of the newly freed slaves, such as obtaining food, medical care, communication with family members, and jobs.

Travelers unknowingly carried epidemics of cholera and yellow fever along the river corridors, which broke out across the South and caused many fatalities, especially among the poor.

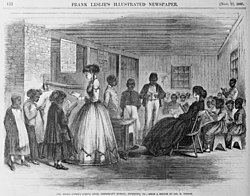

Howard turned over confiscated property including planters' mansions, government buildings, books, and furniture to superintendents to be used in the education of freedmen.

[clarification needed] These readers included traditional literacy lessons, as well as selections on the life and works of Abraham Lincoln, excerpts from the Bible focused on forgiveness, biographies of famous African Americans[example needed] with emphasis on their piety, humbleness, and industry; and essays on humility, the work ethic, temperance, loving one's enemies, and avoiding bitterness.

[20] J. W. Alvord, an inspector for the Bureau, wrote that the freedmen "have the natural thirst for knowledge," aspire to "power and influence … coupled with learning," and are excited by "the special study of books."

Beginning in 1890 in Mississippi, Democratic-dominated legislatures in the South passed new state constitutions disenfranchising most blacks by creating barriers to voter registration.

Northerners were beginning to tire of the effort that Reconstruction required, were discouraged by the high rate of continuing violence around elections, and were ready for the South to take care of itself.

[24] The building and opening by the AMA and other missionary societies of schools of higher learning for African Americans coincided with the shift in focus for the Freedmen's Aid Societies from supporting an elementary education for all African Americans to enabling African-American leaders to gain high school and college educations.

Generally, they believed that Blacks needed help to enter a free labor market and rebuild a stable family life.

Under the direction and sponsorship of the Bureau, together with the American Missionary Association in many cases, from approximately 1866 until its termination in 1872, an estimated 25 institutions of higher learning for black youth were established.

[30] Even before the war, blacks had established independent Baptist congregations in some cities and towns, such as Silver Bluff and Charleston, South Carolina; and Petersburg and Richmond, Virginia.

[30] After the war, freedmen mostly withdrew from the white-dominated congregations of the Baptist, Methodist and Presbyterian churches in order to be free of white supervision.

Northern mission societies raised funds for land, buildings, teachers' salaries, and basic necessities such as books and furniture.

Well-meaning Bureau agents were understaffed and weakly supported by federal troops, and found their investigations blocked and authority undermined at every turn by recalcitrant plantation owners.

Bureau agents did negotiate labor contracts, build schools and hospitals, and aid freedmen, but they struggled against the violence of the oppressive environment.

Henry Jones, accused of being the leader of the purported insurrection, was shot and left to burn by whites, but he survived, badly hurt.

[35][34] In March 1872, at the request of President Ulysses S. Grant and the Secretary of the Interior, Columbus Delano, General Howard was asked to temporarily leave his duties as Commissioner of the Bureau to deal with Indian affairs in the west.

Upon returning from his assignment in November 1872, General Howard discovered that the Bureau and all of its activities had been officially terminated by Congress, effective as of June.

But insurgents showed that the war had not ended, as armed whites attacked black Republicans and their sympathizers, including teachers and officeholders.

"[37] All documents and matters pertaining to the Freedmen's Bureau were transferred from the office of General Howard to the War Department of the United States Congress.

Thomas Ward Osborne, the assistant commissioner of the Freedmen's Bureau for Florida, was an astute politician who collaborated with the leadership of both parties in the state.

These outlaws were thought to be people from other states, such as Texas, Kentucky and Tennessee, who had been part of the rebel army (Ku Klux Klan chapters were similarly started by veterans in the first years after the war.)

Slavery had been prevalent only in East Texas, and some freedmen hoped for the chance of new types of opportunity in the lightly populated but booming state.

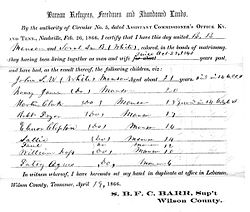

These constitute a major source of documentation on the operations of the Bureau, political and social conditions in the Reconstruction Era, and the genealogies of freedpeople.

[54][55][a] The Freedmen's Bureau Project[57] (announced on June 19, 2015) was created as a set of partnerships between FamilySearch International and the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA), the Smithsonian's National Museum of African American History and Culture, the Afro-American Historical and Genealogical Society (AAHGS), and the California African American Museum.