Frigatebird

Able to soar for weeks on wind currents, frigatebirds spend most of the day in flight hunting for food, and roost on trees or cliffs at night.

Classified in the genus Limnofregata, the three species had shorter, less-hooked bills and longer legs, and lived in a freshwater environment.

[7]Frigatebirds were grouped with cormorants, and sulids (gannets and boobies) as well as pelicans in the genus Pelecanus by Linnaeus in 1758 in the tenth edition of his Systema Naturae.

He described the distinguishing characteristics as a straight bill hooked at the tip, linear nostrils, a bare face, and fully webbed feet.

The genus name Atagen had been coined by German naturalist Paul Möhring in 1752, though this has no validity as it predates the official beginning of Linnaean taxonomy.

[13] Urless N. Lanham observed in 1947 that frigatebirds bore some skeletal characteristics more in common with Procellariiformes than Pelecaniformes, though concluded they still belonged in the latter group (as suborder Fregatae), albeit as an early offshoot.

[14] Martyn Kennedy and colleagues derived a cladogram based on behavioural characteristics of the traditional Pelecaniformes, calculating the frigatebirds to be more divergent than pelicans from a core group of gannets, darters and cormorants, and tropicbirds the most distant lineage.

[15] The classification of this group as the traditional Pelecaniformes, united by feet that are totipalmate (with all four toes linked by webbing) and the presence of a gular pouch, persisted until the early 1990s.

[16] The DNA–DNA hybridization studies of Charles Sibley and Jon Edward Ahlquist placed the frigatebirds in a lineage with penguins, loons, petrels and albatrosses.

[20] Molecular studies have consistently shown that pelicans, the namesake family of the Pelecaniformes, are actually more closely related to herons, ibises and spoonbills, the hamerkop and the shoebill than to the remaining species.

[21][22] In 1994, the family name Fregatidae, cited as described in 1867 by French naturalists Côme-Damien Degland and Zéphirin Gerbe, was conserved under Article 40(b) of the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature in preference to the 1840 description Tachypetidae by Johann Friedrich von Brandt.

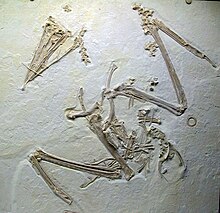

[23] The Eocene frigatebird genus Limnofregata comprises birds whose fossil remains were recovered from prehistoric freshwater environments, unlike the marine preferences of their modern-day relatives.

[28][29] A tarsometatarsus and pedal phalanx from the Lower Eocene London Clay of the Walton-on-the-Naze resembles Limnofregata, but being notably larger and distinct in other ways, was tentatively referred to Marinavis longirostris due to similar stratigraphy, geography, size, and presumed frigatebird affinities.

[30] A cladistic study of the skeletal and bone morphology of the classical Pelecaniformes and relatives found that the frigatebirds formed a clade with Limnofregata.

[48] Great frigatebirds marked with wing tags on Tern Island in the French Frigate Shoals were found to regularly travel the 873 km (542 mi) to Johnston Atoll, although one was reported in Quezon City in the Philippines.

[52] Highly adept, they use their forked tails for steering during flight and make strong deep wing-beats,[46] though not suited to flying by sustained flapping.

[46] According to a study in the journal Nature Communications, scientists attached an accelerometer and an electroencephalogram testing device on nine great frigatebirds to measure if they slept during flight.

[53] The average life span is unknown but in common with seabirds such as the wandering albatross and Leach's storm petrel, frigatebirds are long-lived.

[54] Despite having dark plumage in a tropical climate, frigatebirds have found ways not to overheat—particularly as they are exposed to full sunlight when on the nest.

A single white egg that weighs up to 6–7% of mother's body mass is laid, and is incubated in turns by both birds for 41 to 55 days.

[46] The duration of parental care in frigatebirds is among the longest for birds, rivalled only by the southern ground hornbill and some large accipitrids.

[44] Conversely tuna fishermen fish in areas where they catch sight of frigatebirds due to their association with large marine predators.

[63] A heavy chick mortality at a large and important colony of the magnificent frigatebird, located on Île du Grand Connétable off French Guiana, was recorded in summer 2005.

Chicks showed nodular skin lesions, feather loss and corneal changes, with around half the year's progeny perishing across the colony.

An alphaherpesvirus was isolated and provisionally named Fregata magnificens herpesvirus, though it was unclear whether it caused the outbreak or affected birds already suffering malnutrition.

Larger numbers formerly bred on the island, but the clearance of breeding habitat during World War II and dust pollution from phosphate mining have contributed to the decrease.

[44] As frigatebirds rely on large marine predators such as tuna for their prey, overfishing threatens to significantly impact on food availability and jeopardise whole populations.

[59] As frigatebirds nest in large dense colonies in small areas, they are vulnerable to local disasters that could wipe out the rare species or significantly impact the widespread ones.

[74] The great frigatebird was venerated by the Rapa Nui people on Easter Island; carvings of the birdman Tangata manu depict him with the characteristic hooked beak and throat pouch.

[76] Maritime folklore around the time of European contact with the Americas held that frigatebirds were birds of good omen as their presence meant land was near.